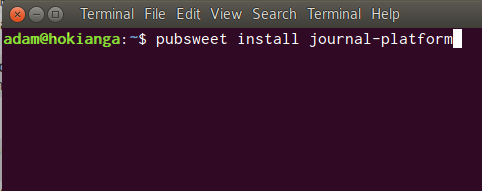

We have a webinar coming up soon for Editoria. In anticipation of that I thought I’d write a little overview of what was involved in building the product. So… Starting with a little hand drawn schematic…

The above shows all the moving parts that we had to consider, and build, to make Editoria what it is. From the user’s perspective, it looks like one app – the Editoria interface – where they can upload a docx file (or files) and start work on producing a book.

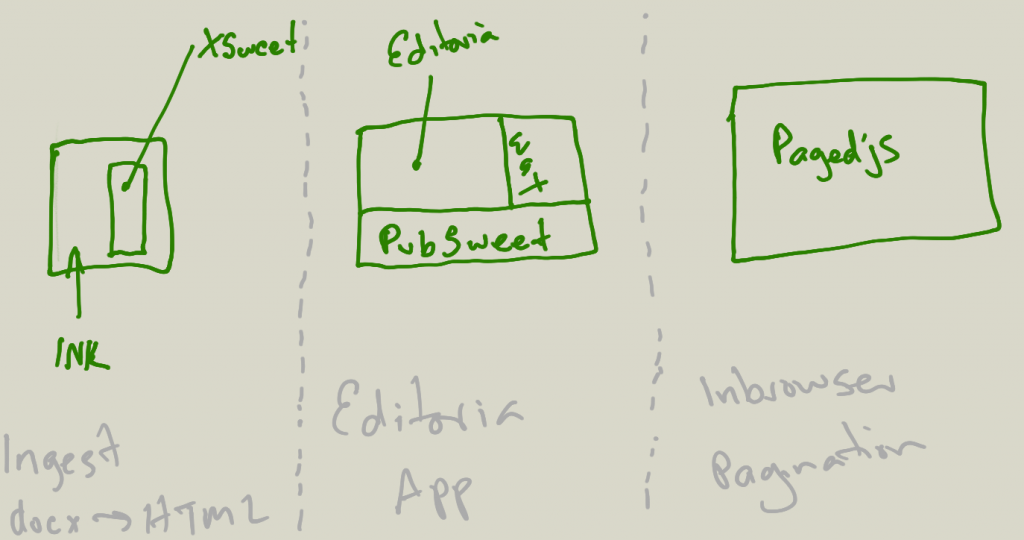

From an ‘under the hood’ perspective, it looks like the following…

As it happens, we had to build all of the above to make it possible… So, here is a list of all the parts starting from ingest…

Ingest

Ingest consists of 2 parts:

- INK

- XSweet

INK is a job processing workhorse. Essentially it will run any kind of job you want and ‘steps’ are written for specific kinds of jobs/processes. These are a kind of ‘wrapper’ around executable code. INK has an API that enables platforms like Editoria to send files to it and request a specific set of steps to be run, and then return the result. In this instance, INK runs a set of steps that wrap up XSweet.

XSweet is a set of scripts that take a docx file and convert it to HTML. It is very modular and can be pretty easily extended and improved. It can also be customised per use case.

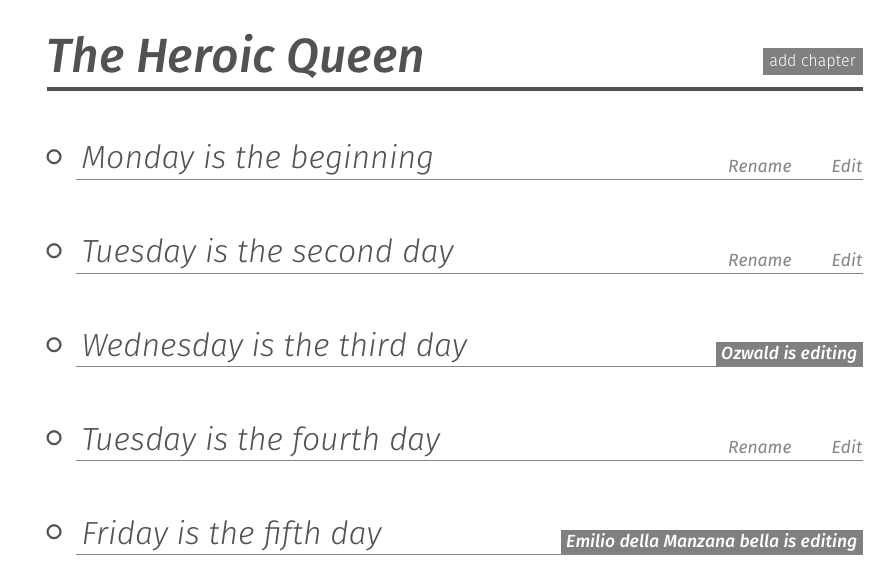

So, on the ingest stage it looks like the following to the user:

- user logins in to Editoria

- they create a new book from the book dash

- they vlivk on the new book

- from the book builder interface they choose ‘upload multiple word files’ or ‘upload word’.

- they select the word file(s) from a system dialog

- these files are automagically appear ‘in the book’ and can be edited

- note : in the case of multiple docs files, if the files have been named according to a simple convention, Editoria will create each new chapter and automatically populate the structure of the book and load the content in the right place

From the tech side the following happens:

- when a word doc file or files are selected, the files are sent to INK via the INK API, with a request to convert to docx using the XSweet steps

- INK runs the docx file(s) through the XSweet steps, creating HTML

- when the job is done, INK signals Editoria that the files are good to go

- Editoria grabs each file when it is ready and puts in the the right chapter, creating the chapter if multiple word files are uploaded at once

So… we had to build all of the above. First, INK exists because, crazy as it sounds, we could not find an elegant open source pipeline manager to manage jobs like this. So we decided to build from zero. In addition, which also sounds crazy, there is not a comprehensive open source library out there for converting docx to HTML that was easy to extend or customise for different use cases. We certainly know of many scripts for docx->html (many are listed on the XSweet site), but they are either unmaintained, or difficult to extend. So, unfortunately, we had to build that also.

Editoria App

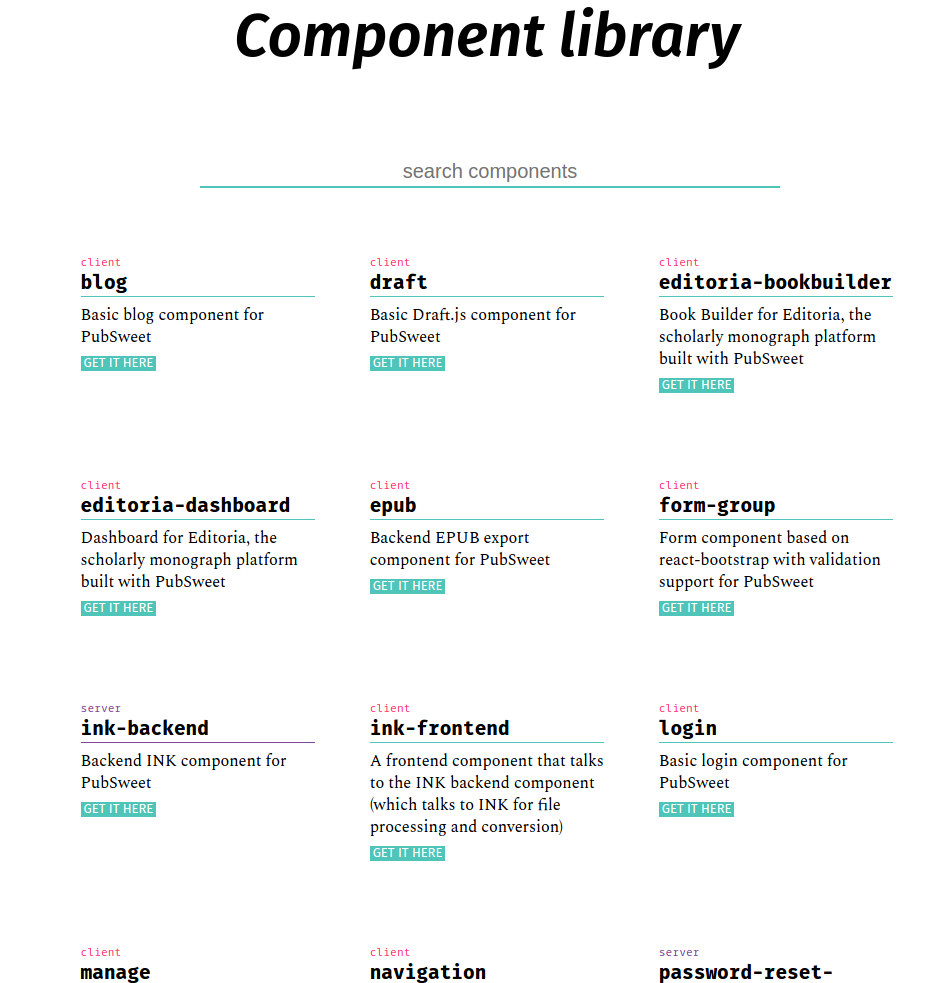

The Editoria App is what people think of ‘as Editoria’. Everything the user interacts with is, on the surface, Editoria interfaces in the browser. However, Editoria comprises of 3 main parts:

- PubSweet

- the Editoria interfaces

- Wax

PubSweet is the ‘under the hood’ CMS that enables apps like Editoria to be built on top. PubSweet is a Node/React application written entirely in Javascript and it sits on the server and provides a ‘wrapper’ for the Editoria interfaces. You can think of PubSweet as a ‘headless’ CMS that thinks like a publishing system. Once again, when we started (and still today) there was nothing out there that could realise multiple publishing use cases, as diverse as micropubs, books, journals, content aggregation etc, built on top of the same CMS. So we had to build it ourselves. PubSweet is now pretty mature and indeed supports multiple publishing platforms – at last count I think that totals 6 platforms built on top of PubSweet (and it is early days).

The Editoria interfaces are the ‘web pages’ that make up the Editoria application. This includes the dashboard, the book builder etc… these are all custom code written on top of PubSweet to realise the Editoria use case / platform.

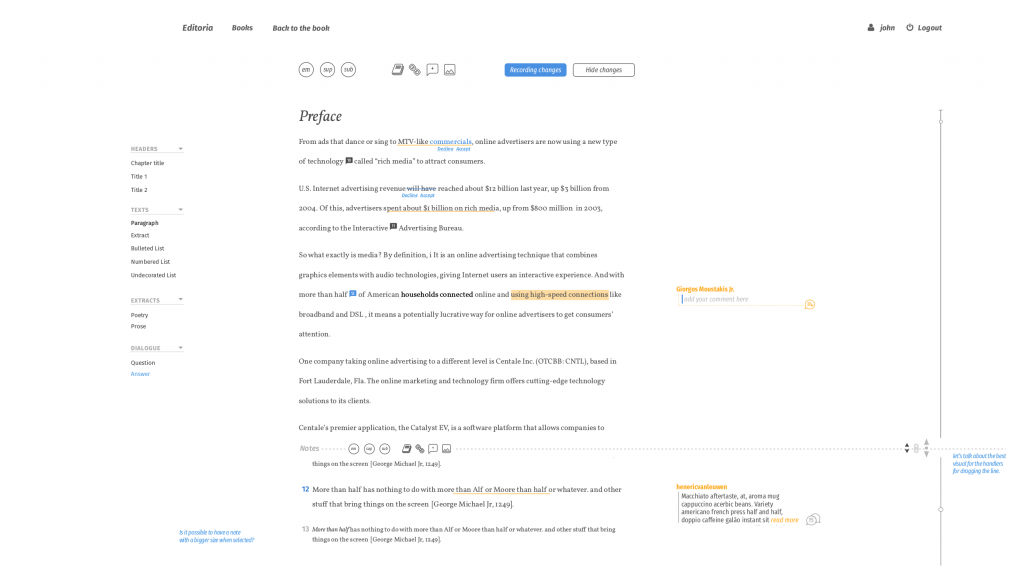

Wax is an online editor, it is so sophisticated we prefer to call it a web-based word processor. It is actually an Editoria interface, except that it is so complex and such a critical part of any online publishing tool, that it is a product in its own right. Nothing like this existed either, so we built our own (typical WYSIWYG editors are not sophisticated enough for the publishing use case).

PagedJS

From Editoria, you can press a button and have a book appear in the browser. If you print from the browser, you will then get a PDF ready to take to the printers with all the typographical bells and whistles that books need. It looks magical. We currently use Vivliostyle for this but we have hit many limitations with the software. We reached out to the org that produces the code but they weren’t ready to collaborate to improve the product. Hence, unfortunately, we had to build our own. Soon we will replace Vivliostyle with this new offering. The speed of dev has been incredibly fast on paged.js (working title) and so watch this space for some exciting news.. there are some early demos in the pagedjs repo if you are interested.

Summary

…. So, as you can see, Editoria is more complex than it appears to the eye of the user. Also, the crazy thing is that most of these parts should have existed already, but, crazy as it is, they didn’t exist. There has been no full page, open source, editor out there gives the source control and extensability required for the publishing use case. The docx conversion tools available do not yet do a good enough job of the conversion, and are not easy to customise. There is no headless CMS that ‘thinks like a publisher’ and would help us build Editoria; and we had to create a pagination engine (paged.js) because the one open source option couldn’t give us what we needed and we failed at trying to help them improve the product.

Its not like we wanted to build all this, but the sad fact is for the publishing industry the web is still an innovation they haven’t embraced (except as a distribution medium). So while all of these parts (or many of them) should exist, the sad truth is they did not exist. We did a pretty good look around to see if we could save ourselves the effort before embarking on these projects. We did, for example, bank on Substance Lens Writer for our editor, but it was not maintained and proved unstable, and our eventual assessment was that it was better to start again – hence Wax. We also have gone a long way down the path of using and promoting Vivliostyle, until it became apparent that neither the technology nor the technology providers could get us to where we needed to be… consequently, after implementing Vivliostyle (it is still baked into Editoria) we started a new approach to this problem – Pagedjs.

So, we had to build all of this ourselves… the good news is, that all of these moving parts are reusable in other scenarios… so you can take whatever you like from the above, and add it to your own product and hopefully that will fuel the publisher sectors ability to innovate and transform their products and workflows.