NB Now updated, renamed, and moved to here

https://www.adamhyde.net/leadership-diversity-and-sector-change-in-open-source/

v 0.5.1 – Feb 3 “clean up”

v 0.5 – Feb 2 “rewrite, thanks to Andrew Rens”

v 0.4 – Jan 31 “add facilitation mode on product dev”

v 0.3 – Jan 30 “added more detail on good collaboration”

v 0.2 – Jan 29 “some lessons for open source added”

v 0.1 – Jan 28

needs more content, fact checking, structure. Be patient with me! Will improve it in the next days

[new working title]

Leadership, diversity and sector change in open source

Recently I have been pondering how sector change is possible. Sector change, specifically to change the publishing sector, is a key goal of mine. I don’t want to be involved in just improving it, I want to change it completely – so even the language we use to describe what was once “publishing” is shifted into another domain, namely knowledge production.

But how to do such a thing? How can you shift an entire sector sideways and rewrite processes, tools, value systems, expectations, career paths, language? The whole works.

Examples of sector change

Community building begins with convincing people who don’t need to work together that they should. - John Abele

Recently I have found some clues to these questions in the writings of John Abele (founder of Boston Scientific), particularly “Bringing Minds Together“. His writings have inspired me to look again at how I see open source.

Early in his career, John was involved with some technologies for non-invasive surgery. Today the stuff is day-to-day. Back then, surgery was invasive by definition. Back then, talk of non-invasive instruments for surgery would be like talking about screen-less phones today. Imagine trying to sell that.

So, he had a hard time trying to sell a new idea that he knew could transform the medical sector. As he writes, “We were developing new approaches that had huge potential value for customers and society but required that well-trained practitioners change their behaviour. … Despite the clear logic behind the products we invented, markets for them didn’t exist. We had to create them in the face of considerable resistance from players invested in the old way and threatened with a loss of power, prestige, and money. ”

This is what we face with Coko (Collaborative Knowledge Foundation) at the moment. Smart people that are under the painful burden of outdated workflows and technology are often resistant to change because it requires them to change their behaviours. It is a huge problem if you wish to modernise the way knowledge is produced and reduce that burden on them.

In John’s case, he drew on some insights he had gathered early on in his career from Jack Whitehead, CEO of Technicon, a small company that had the patent for a new medical device. When trying to bring this product to market, Technicon had the odds stacked against it. No one from the lab technicians, through to the professional societies and manufacturers, wanted anything to do with it. So Jack drummed up some interest from early adopter types and came up with a surprising next step, he “told all interested buyers that they’d have to spend a week at his factory learning about it.”

That sounds like an odd sales pitch now, but back then (early 60s), apparently it sounded a whole lot more crazy. However, Jack convinced a handful of excited early adopters to take that step, and brought them in.

In this week, the early adopters were not treated like customers but like partners. They were part of the team. They came to know each other, they worked together, they shaped the product. They became the team. As John says:

“When the week ended, those relationships endured and a vibrant community began to emerge around the innovation. The scientist-customers fixed one another’s machines. They developed new applications. They published papers. They came up with new product ideas. They gave talks at scientific meetings. They recruited new customers. In time, they developed standards, training programs, new business models, and even a specialized language to describe their new field.”

This meeting of once potential customers, now team members, not only contributed to the design of the technology but then took it out into the world and fueled adoption and interest in the product. What had humble roots as a group of early adopters, was on its way to creating large-scale change.

John witnessed this process and realized this was strategy not whimsy: “[Jack] was launching a new field that could be created only by collaboration—and collaboration among people who had previously seen no need to work together.”

John went on to form Boston Scientific and refined this strategy further with Andreas Gruentzig when introducing the balloon catheter to a hostile and uninterested market. Again he was successful in catalyzing this kind of large-scale change.

Astonishing. You could have told the same story about any number of successful open source projects. Indeed, John reflects on the parallels to open source:

“Just as Torvalds helped spawn the open source movement, and Jimmy Wales spearheaded the Wiki phenomenon, Andreas [Gruentzig] had created a community of change agents who carried his ideas forward far more efficiently than he could have done on his own.”

The strategy in both cases started with a simple idea – to create a community of change agents.

Leadership

Leaders need to cede control, not vigorously exert it. - John Abele

The creation of a community where collaboration can flourish is a product of a particular kind of leadership – what John calls ‘collaborative leadership’. I have also seen this in many places including open source, unconferences, and Book Sprints (which I founded). In the later two cases we call the collaborative leader a facilitator.

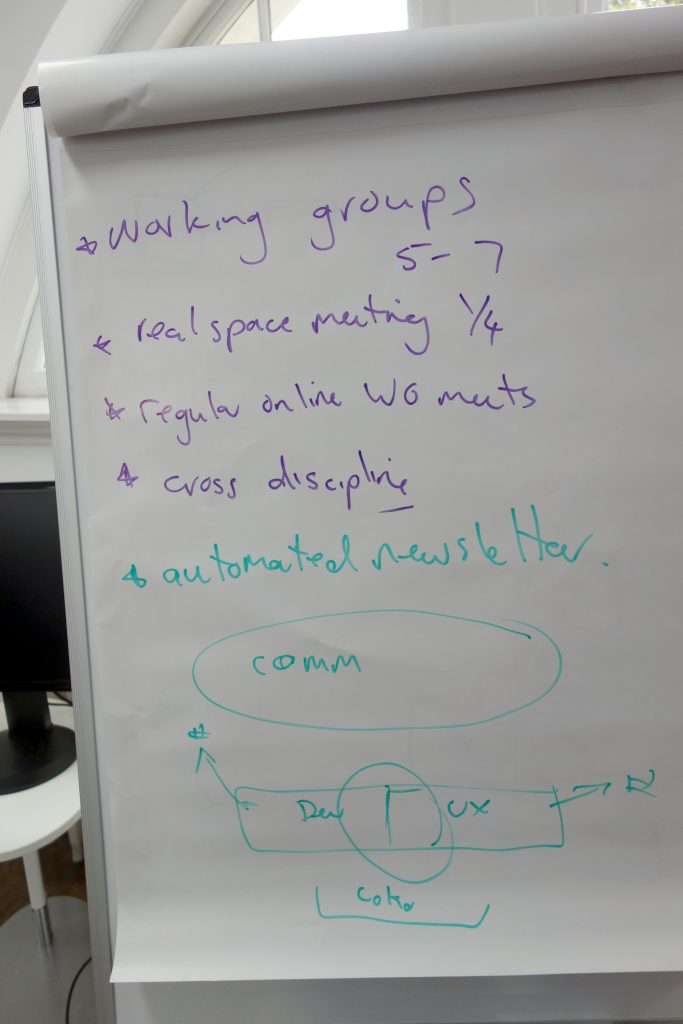

There are many modes of facilitation and choosing the right characteristics, the right mode, to create the right environment is critical. John gives some interesting tips on what this mode look like. The characteristics that I glean from his article includes the ability to:

- foster “collaboration among people who had previously seen no need to work together”

- manage egos

- earn trust

- respect stakeholder interests

- be authentic

- “listen, share, and ask good questions”

- share the credit

- use “we” not “I”

- support the choice of ‘alternative methods’

- create rituals

- create non-traditional spaces and experiences to come together

- ensure people “feel like partners”

- be willing to take direction from the ‘customer – participants’

- build trust over control

- “point out the deficiencies in the tools” you are making

- present ideas “in ways that [cry] out for input”

A good facilitator knows this language and these modes and can apply them but there are different requirements for facilitation depending on what you are trying to achieve. Book Sprint facilitation, for example, is much more product-orientated (books) than Unconference facilitation and requires a different set of strategies and tools. Most of the issues above I would categorize as being general rules of facilitation, however those modes that hint at enabling a group to create large-scale change are the most interesting here. I think the last four points are telling:

- be willing to take direction from the ‘customer – participants’

- build trust over control

- “point out the deficiencies in the tools” you are making

- present ideas “in ways that [cry] out for input”

The most important issue at stake here for the facilitator is to create the space so others will come up with the product solution. This kind of facilitation creates vacuums, spaces where solutions don’t yet exist. This kind of facilitation is focused on a diverse range of stakeholders to design the product. This kind of facilitator doesn’t have all the answers but instead highlights problems and brings people together to create the solutions. To do this, typical facilitation modes are necessary to enable an environment of trust and sharing while enabling the participants to own the problems and create the productized solution. This comprises a very specific mode of facilitation.

Can Open Source do this?

Open source software is about people.

- Sacha Greif

While these examples are about proprietary technology, it is not the proprietariness at stake here, it is the process that is important – and good process is the product of good facilitation. While facilitation is active in many open source projects, it is not necessarily so, and where it does exist it is not typically with the kind of framing John has pioneered. Sure projects want people to use their software, they want to be sustainable, they don’t want to do all the work, they want community. However, open source projects are typically interested in bringing in more developers yet not necessarily on fueling wide-scale adoption (as odd as that may sound) and this informs the kind of people involved and the facilitation strategy employed.

There is a great article by Telescope founder Sacha Greif that illustrates this quite well. Sacha writes – “So why did I decide to make Telescope open source in the first place? It’d be easy to answer with typical clichés about “giving back to the community” or “believing in free software”….But the truth is a lot more pragmatic and selfish: I thought it would be a good way to get other people to help me accomplish my own goals, for free.”

Sacha goes on something of a journey with Telescope, undertaking some course corrections, and concludes “when it comes to open source software, software actually plays a fairly minor role. Open source software is about people.”

I think this illustrates quite nicely where the mindset of open source projects generally are. Sacha went past the ideal of ‘build it and they will come’, a very tech-centric way of seeing things, through to understanding that the secret to success for an open source project lies with people, not technology. Sacha transitioned from developer to facilitator.

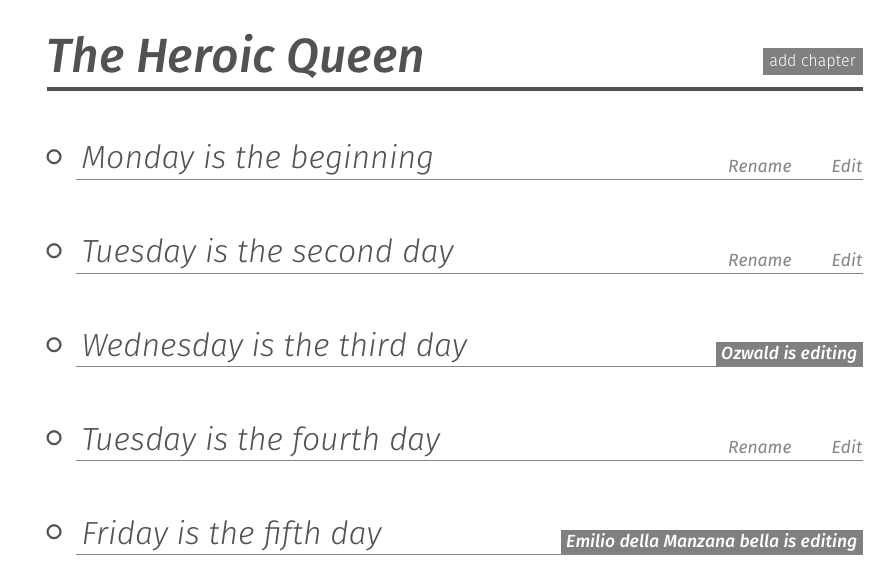

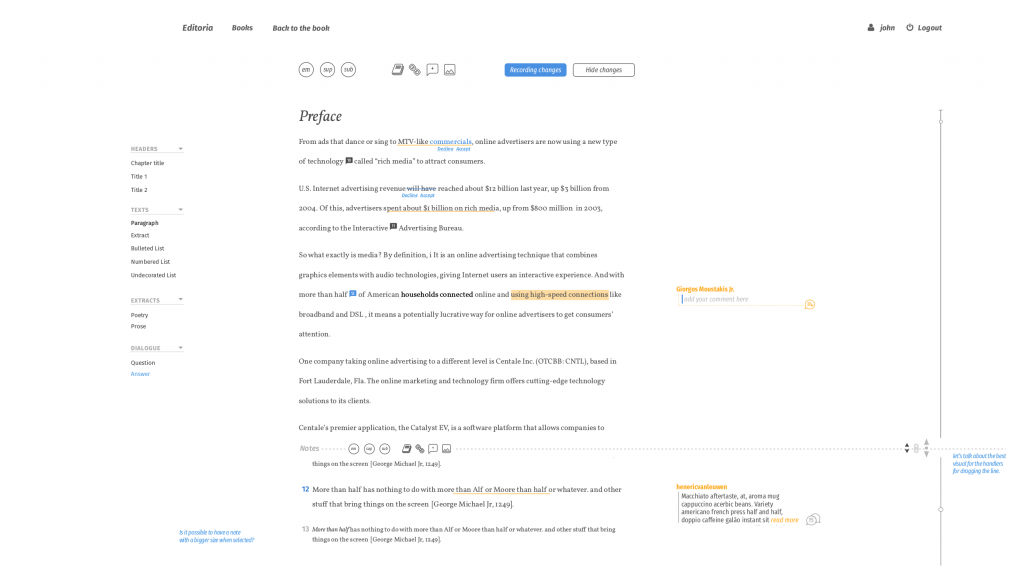

That is very laudable. However, facilitating developers to build your technology is very different from facilitating a diverse set of stakeholders to develop a product, fuel adoption, change user behaviours and put your project on the path to creating wide- scale change. The later requires involving different stakeholders and it involves a different mode of facilitation.

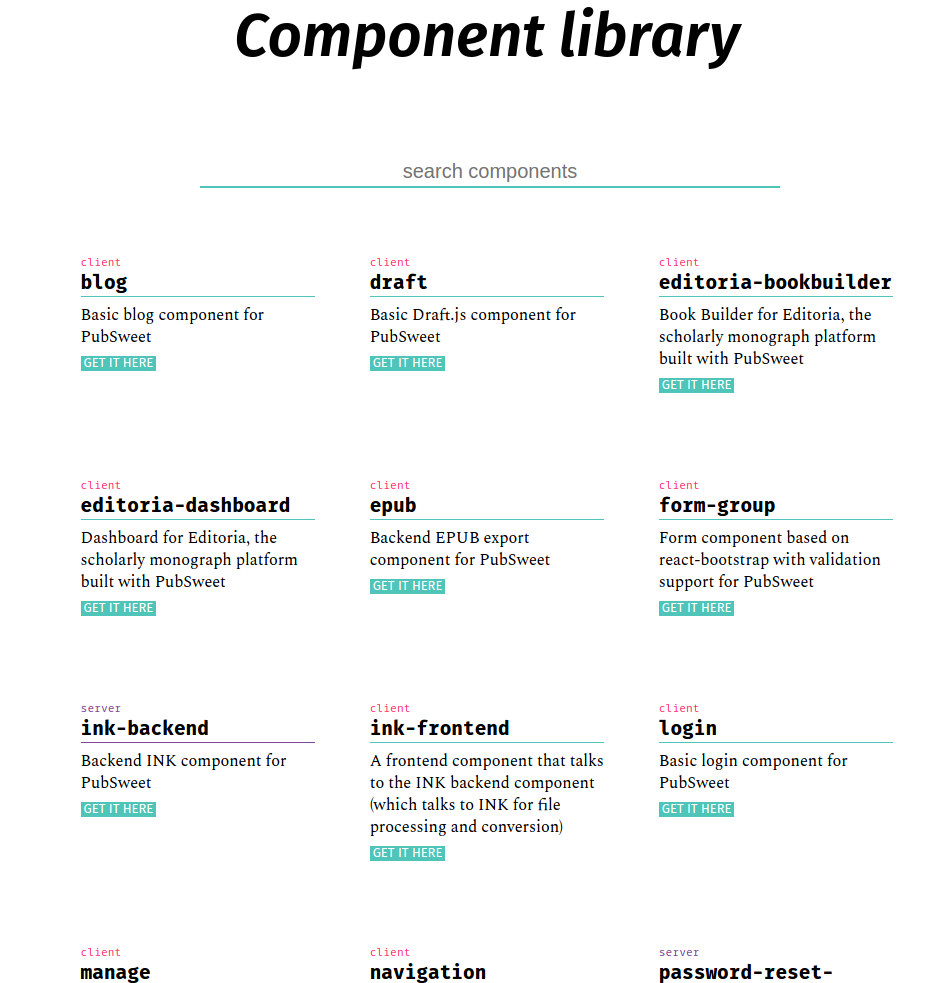

This is where open source is getting in its own way. Open source is about employing the right tools, facilitation included, to expand your developer base. That’s fine if you are building the plumbing – open source libraries, under the hood services, back end functionality, and so on can all be built well using this kind of method. However, if you want to be part of a team that creates wide scale change through a user-facing product, then I would suggest that open source as a culture-methodology is not the way to do it. Open source is, at its heart, a techno-meritocratic culture. Great for building under the hood tools (builders building for other builders), terrible for producing products.

This shouldn’t be surprising. Somehow however it is. But then again when we look closely it sort of makes sense…Even the term “Open Source” expresses just how much the code and those that make it form the core orientation and value metrics. Additionally, in a typical open source project, the person at the top is the person with all, or most of, the technical answers (in a techno-meritocratic culture you can only not know so much before you ain’t the boss anymore- and become the famed benevolent dictator. And they are the culture keepers, the arbitrators, the facilitators. This sets the scene for a particular kind of facilitation that privileges the involvement of those with technical skills over anyone else. This all points to a certain kind of mono-cultural community.

To see a good example of this, have a look at this post about Octocat. The entire emphasis of this article is to find ways to celebrate ‘non-code’ contributions. The term ‘non-code’ in itself is an indicator that anything other than code only has value by association (imagine a manager in any industry thanking a group of workers for their ‘non-management contributions’). Octocat was developed to measure ‘non-code contributions,’ and to be effective ‘non-coders’ must log their activities in the projects issue tracker. Hence all contributors must use the same tools that the developers use. Octocat is a good project but it highlights just how focused the entire culture of open source is on technical development and wants everyone to fit into that paradigm. I believe this is at the cost of the product, adoption, and the potential change the product could make if managed differently.

Diversity

"Diversity creates better projects. So, why aren't designers participating in open source?" - Una Kravets

So, what must open source change to enable a project to create massive change? Open source requires a different kind of culture. Open source must diversify away from technocratic meritocracy to become diverse communities of stakeholders. Unfortunately just the opposite is happening – ‘non-coders’ are being chased away in droves.

This is not new news. Open source has sort of known there was something wrong with its culture for sometime. The wholesale migration to closed source desktops (Apple) by the open source development world highlights this. Why did we see this enormous migration? Because OSX is ‘nicer to use’. That tells us something. Open source has generally failed on user experience (I must note that I do not believe that to be the case now for open source desktops) and it has failed because open source culture is not inclusive of designers. The mono-culture has very firm boundaries for what it can do well, and it cannot provide good UX unless it diversifies.

Una Kravets has done a very nice presentation on these issues. In this presentation, Una goes into detail why designers are not involved in open source and how to enable the conditions to improve participation.

The point here is that it is not just a question about representation (and the shockingly low numbers of women involved), which is an effort we should all support in its own right, it is also a question of the health of a product. As Una has argued well, ‘diversity creates better projects’. I would like to take that one step further and suggest that diversity not only creates better projects, it creates better conditions for wide-scale adoption and change. To develop a successful product, you need to have the customers designing the solution, you need UX designers to finesse the interactions, designers to make it look great, evangelists to present it at conferences; you need developers to do the plumbing, you need users for the feedback, and you need facilitators that can bring all these people together and enable them to function as a passionate, problem-solving, engaged whole. To do that , all these people need to be drawn from a diversity of contexts, valued equally, and they must all have a say in what it is that you are creating. You need what John Abele calls ‘a community of change agents,’ not a community of developers.

Involving and privileging only developers is not the right kind of culture to achieve success with a product. We must do away with the techno-meritocratic culture of open source and replace it with a more change-centric paradigm – the community of change agents. The root of this new kind of product development culture requires a specific kind of facilitation (‘collaborative leadership’), and the passionate involvement of a diverse set of stakeholders.

Summary

I love open source, I think it has done amazing things. I am a huge free license and free culture advocate. I started communities of documentation writers to support open source, have initiated many software projects – all open source – and contributed in humble ways to others. However, the writings of John Abele have lead me on a curious journey. While I was always troubled by the technocratic nature of open source, I figured it was a transformational movement and I would figure out a way to exist within in and assist where I can. However, I am not seeing very clearly, that, while there are individual exceptions, open source as a movement has its own hard-coded limits. Unfortunately, these are limits that stunt its effectiveness and its ability to create wide-scale change, especially with user-facing products. Unfortunately, the open source movement itself is barely cognizant of these limitations, why they exist, and how they could be removed.

tbc

older version:

Recently I have been pondering how sector change is possible. Sector change, specifically to change the publishing sector, is a key goal of mine. I don’t want to be involved in just improving it, I want to change it completely – so even the language we use to describe what was once ‘publishing’ is shifted into another domain, namely knowledge production.

But how to do such a thing? How can you shift an entire sector sideways and rewrite processes, tools, value systems, expectations, career paths, language. The whole works.

It seems to me that the critical methodologies for wide-scale change like this are ‘almost native’ to open source. I’ll explain the ‘almost’ in a bit. But as an opener, open source has the ability to produce massive change. I don’t mean that open source can change the way that software is produced, we all know that. I mean the strategy for running a successful open source project is the same strategy you should adopt if you are trying to enable change, or massive change – of a sector, for example. I’m kind of surprised to arrive at this conclusion. I always loved open source but I am starting to realise that I have loved it for the wrong reasons.

Over the last 20 years or so of being involved in open source I have felt myself in a kind of continual falling forward into open source values. Who can’t love open source when you get down to it? The idea that software should be available to anyone that wants it, to do with it as they please. Its a great idea. It is about empowerment and that is something powerfully valuable it itself.

Empowerment through open source occurs because people have access to free tools and for this to happen we need generous tool makers. That highlights more good values active in open source, namely sharing. The fact that the technically gifted have brought these tools into our lives and generously shared them for free is something we should celebrate.

Of course, the sharing has its own reward system and isn’t all altruistic. Paid programmers building everything from Facebook to the technology that runs your dentist’s office systems (a reference to this ridiculous article in case you missed it) could not do their work without all the open source libraries they can handily import for free into their projects. Also, to ensure they don’t have to do the same work again in other projects, possibly for different clients or employers, they also share what they build (where possible). By reusing your own work and that of others like this, the total workload is then also decreased and people can get further faster. Progress can be made. Programmers can also enhance their reputations if their work is re-used by other programmers. This becomes value in the market place. Hence this sharing has turned into an economy. It’s a good one, who couldn’t love an economy that encourages sharing? This economy also makes many open source software projects sustainable so the whole system has a beautiful internal logic.

The openness of all this is also something to be valued. Exposing the code to all eyes is a famous strategy for reducing bugs. It’s also touted as a strategy for increasing security. It also means programmers can learn from code developed by others (both the good and the bad). Openness and transparency also have a lot of utility in this world, and open source has proven this utility time and time again. Openness is not only good for the code, but it makes us feel good (if we are not too tainted by the proprietary way of life).

Then there is community. You can’t go far into a conversation about open source without mentioning community. Community is the metric for the well-being of any open source project and seeing a healthy open source community is a sight to behold. It is astonishing. All these people somehow, impossibly, co-ordinating to pull in (more or less) the same direction. Good governance plays a role in this after a certain threshold of participants has been exceeded and good governance in itself is quite miraculous to consider. How do the guardians make the wise decisions necessary to balance participation and technical development, uptake, funding, systems, protocols, agreements…the whole works. To consider the day-to-day decisions, project leads must need to make and the context in which they operate is quite dizzying.

I love all of this.

These are many of the reasons I have loved open source. I mean, who couldn’t love sharing, transparency and community? Well, there are actually many, many other values! But I want to think of the open source developers as very cold-hearted. I still believe in good guys and bad guys – the world is more fun that way, more energising. However, as much as I love open source, I think I have been in love with it for the wrong reasons.

How did I get to this realisation?

Recently I have been reading the writings of John Abele (founder of Boston Scientific). This has lead me down another path and provided me with fresh lens through which to value open source. Strange for me as I am allergic to proprietary-ness and John Abele is a good proprietary citizen. Ranked high on the Forbes rich list – net worth 600 million I believe – John has made a lot of money from Intellectual Property, specifically via the sale of medical instruments.

So, why did this entrepreneur, with whom I would initially assume I would share few values, inspire me to look again at how I valued open source? Well…it all comes down to the fact that John did achieve wide scale, sector-wide, change and he did it in a way that is radical to proprietary culture, but I would consider more native, almost native perhaps, to open source.

Early in his career, John came up with some technology for non-invasive surgery. Today the stuff is day to day. Back then surgery was invasive by definition. Talk of non-invasive instruments for surgery back then would be like talking about screen-less phones today. Imagine trying to sell that.

So, he had a hard time trying to sell a new idea that he knew could transform the medical sector. He did transform a sector, so how did he do it?

John has written quite a bit on how he was able to do this, in particular he writes a lot about collaboration and even brought a conference center specifically to change it into a center for collaboration. But it is his ideas on change that most interest me. His article in this HBR article “Bringing Minds Together” gives some good insights. In this article John speaks of how openness can accelerate adoption where ‘walled’ processes have failed:

https://hbr.org/2011/07/bringing-minds-together

I really encourage you to read that article, I summarise it in part below but the full article is well worth reading.

As he writes:

“We were developing new approaches that had huge potential value for customers and society but required that well-trained practitioners change their behavior. … Despite the clear logic behind the products we invented, markets for them didn’t exist. We had to create them in the face of considerable resistance from players invested in the old way and threatened with a loss of power, prestige, and money. ”

So to overcome this John drew on some insights he had gathered early on in his career from Jack Whitehead, CEO of Technicon, a small company that had the patent for a new medical device. When trying to bring this product to market Technicon had the odds stacked against them. No one from the lab technicians, through to the professional societies and manufacturers wanted anything to do with it. So Jack drummed up some interest from early adopter types and came up with a surprising next step, he “told all interested buyers that they’d have to spend a week at his factory learning about it—and that payment was required in advance.”

That sounds like an odd sales pitch now, but back then (early 60s) apparently it sounded a whole lot more crazy. However, Jack found this handful of excited early adopters and brought them in.

In this week the early adopters were not treated like customers but like partners. They were part of the team. They came to know each other, they worked together, they shaped the product. They became the team. As John says:

“When the week ended, those relationships endured and a vibrant community began to emerge around the innovation. The scientist-customers fixed one another’s machines. They developed new applications. They published papers. They came up with new product ideas. They gave talks at scientific meetings. They recruited new customers. In time, they developed standards, training programs, new business models, and even a specialized language to describe their new field.”

They were on the way to creating large-scale change.

John witnessed this and realized that this was no one-off but “something much bigger was actually going on. [Jack] was launching a new field that could be created only by collaboration—and collaboration among people who had previously seen no need to work together. ”

Astonishing. You could have told the same story about any number of successful open source projects. Indeed after applying this strategy with Andreas Gruentzig some years later with Boston Scientific, introducing the balloon catheter to a hostile and uninterested market, John reflects on the parallels to open source:

“Just as Torvalds helped spawn the open source movement, and Jimmy Wales spearheaded the Wiki phenomenon, Andreas [Gruentzig] had created a community of change agents who carried his ideas forward far more efficiently than he could have done on his own.”

The strategy in both cases was simple. To create a community of change agents.

The change agent meeting became something of a user group, which in turn became a regular symposium, which then grew in size and prestige that it rivaled the established legacy events.

I feel compelled to note that the kind of product development we are talking about here is qualitatively different from developing a product for an organisation. Product development for a sector and creating large scale change is what this post is investigating.

There are many factors that play into the success of this approach. John Abele doesn’t go into detail what these are but he gives some hints, notably the creation of a culture of what he calls ‘leader – followers’ and a specific kind of ‘collaborative leadership’.

I think by ‘leader – followers’ he is referring a culture where everyone has the opportunity to be heard and to participate in the development of the solutions at stake. This kind of environment is what I would describe as strong collaboration and the interesting thing about this kind of approach is that it creates a strong feeling of shared ownership of the output. Who it is that owns the product, who are the best kinds of candidates to make up this group, so that they can go forward and take the product into the world, is a very interesting question and there might be some lessons to be learned here for open source.

John Abele doesn’t provide much detail in his article as to the desired make-up of this group. Beyond stating that they are potential customers there is very little detail on who these people are. It is interesting that they are customers however as this reflects a lot of the ‘itch to scratch’ mantra of the open source world – get people that have a problem to create the solution. However there might be something of an unintended but interesting critique here for open source. The open source world, it might be argued, leans too heavily on programmer involvement and does not necessarily directly involve the people that have the problem – the users – to design the solution.

The creation of a collaborative environment, in turn, is a product of collaborative leadership, which I have also seen in many places including open source and in Book Sprints (which I founded). In the later case we call the collaborative leader a facilitator.

Facilitation is a good art to place at the center of this strategy to create change and I far prefer this framing (‘collaborative leadership’ is a fine term but I think not many people know what this means, whereas I think ‘facilitator’ has much more currency) than those that exist in the open source world ie. ‘cat herder’ or ‘benevolent dictator’. These roles in open source are applied to co-ordinating programmers, and this highlights the techno-meritocratic approach that open source projects tend to subscribe to. Once again, the open source world could be criticized as too closely marrying this leadership to technical expertise. In the cases John outlines, the leaders don’t seem to necessarily have deep technical skills (although they appear to have a hand in the technical development), but they do have strong facilitation skills.

There are many modes of facilitation. Choosing the right characteristics, the right mode, to create the right environment is critical. John gives some interesting tips on what this might look like. The characteristics that I glean from his article includes the ability to:

- foster “collaboration among people who had previously seen no need to work together”

- manage egos

- earn trust

- respect stakeholder interests

- be authentic

- “listen, share, and ask good questions”

- share the credit

- use “we” not “I”

- be willing to take direction from the ‘customer – participants’

- support the choice of ‘alternative methods’

- build trust over control

- create rituals

- create non-traditional spaces and experiences to come together

- make people “feel like partners”

- “point out the deficiencies in the tools” you are making

- present ideas “in ways that [cry] out for input”

A good facilitator knows this language and these modes and can apply them but it is good to recognise that there are different requirements for facilitation depending on what you are trying to achieve. Book Sprint facilitation, for example, is much more knowledge product (books) orientated than Unconference facilitation and requires a different set of strategies and tools. Most of the issues above I would categorise as being general rules of facilitation, however those that are specific to the kind of product-orientated process designed to enable large scale adoption and change are the most interesting. I think the last two points are pointing in this direction:

- “point out the deficiencies in the tools” you are making

- present ideas “in ways that [cry] out for input”

The most important issue at stake here for the facilitator of this kind of project is to create the space so others will come up with the product solution. Don’t have all the answers, instead identify problems and bring people together to create the solutions. To get to that point the typical facilitation modes are necessary to enable an environment of trust and sharing but enabling the participants to own the problems of a product and create the solutions is slightly different from other facilitation modes.

This is the key ingredient, I believe, to the kind of processes that John and colleagues have pioneered and others have made the same observation. The quote below is taken from here:

http://www.kornferry.com/institute/709-growth-through-collaboration-john-abele-s-vision

“…Abele’s success at Boston Scientific was built upon his ability to bring together extremely competitive intellects and create an environment where participants could meet and be candid about what they were working on, including the new techniques, the risks, the benefits and the strategies they employed…’It was about really sharing what they were learning rather than lecturing about what they were teaching’ Abele said. ‘That was powerful because it really accelerated the development of these new technologies in health care — such as revolutionary steerable catheters — and I believed there must be more opportunities to apply this collaboration in a lot of different areas.'”

While these examples are about proprietary technology. It is not the proprietariness at stake here, it is the process that is important – the methods you use to enable early engagement with a wide diversity of stakeholders, bring them into the team, and enable them to be part of the product development. As the passage above states this is a default almost native methodology for open source but also found in the proprietary world. I say ‘almost native’ because I don’t think that this particular framing is the modus operandi for most open source projects, especially those starting out. Sure projects want people to use their software, they want to be sustainable, they don’t want to do all the work, they want community. Most open source projects start off thinking this way but few develop their thinking beyond this starting point, as this beautiful article by Telescope founder Sacha Greif states well:

https://medium.com/@sachagreif/open-source-lessons-learned-two-years-of-telescope-be4ed955b39

Sacha writes – “So why did I decide to make Telescope open source in the first place? It’d be easy to answer with typical clichés about “giving back to the community” or “believing in free software”….But the truth is a lot more pragmatic and selfish: I thought it would be a good way to get other people to help me accomplish my own goals, for free.”

Sacha goes on something of a journey with Telescope, undertaking some course corrections, and concludes “when it comes to open source software, software actually plays a fairly minor role. Open source software is about people.”

I think this illustrates quite nicely where the mindset of open source projects generally are. Sacha went past the ideal of ‘build it and they will come’, a very tech-centric way of seeing things, through to understanding that the real secret to success for an open source project lies with people, not technology.

That is very laudable. However, thinking about how to get people involved to build your technology, is very different from thinking about what you do as a methodology for creating change. I would say one particular issue at stake here is who you involve. If you want to create a technical product, you try and engage developers. If you are trying to create change, you must engage a much wider group of stakeholders.

Open source is a strategy, and a proven one, for product development. All the standard lessons have been learned for this, if not universally shared. Openness, sharing, community can lead to a healthy open source project. However these methods are not only about how the product is developed and who is developing it, but they are the basic tools necessary to create change. When wielded right, these strategies can, and have, lead to large-scale change as John Abele has already proven more than once in his life time and as we have seen with some open source projects.

Although I’m very much in love with the many values of open source I am more interested in their ability to create change which I think is an under considered effect. Its not that creating change is the only thing that should be considered but rather it is a lens that must be considered. It is as important to look at your open source project as a strategy for creating change (which, whether you own it or not, you are trying to do) as much as it is important to see it as being about technology and people.

This is a new realization for me. It opens a lot of doors. It perhaps explains, for example, why many open source projects do not succeed. The famous ‘build it and throw it over the wall’ strategy, for example, that so often leads to a lack of adoption and eventual failure. It perhaps presents an argument that the success of a project aimed at large-scale adoption and change is reliant on the involvement of a diverse range of stakeholders – changemakers not just programmers. It explains why open source is good at developing libraries and tools for other programmers but not necessarily very good at producing platforms for non-programmers. It also explains why other projects succeed even if they are not conscious of this framing.

This is, as if it had to be said, extremely important for publishing right now, or ‘knowledge production’ as I would prefer to talk about it, since sector change is what we need as workflows and outputs are still stuck in (what one may call) ‘post-paper’ processes and thinking. Open source can change this sector if viewed as a strategy for creating change. Massive change. However, if you want change to be native to your open source project, you have to own it. And that’s what I intend to do from now on.