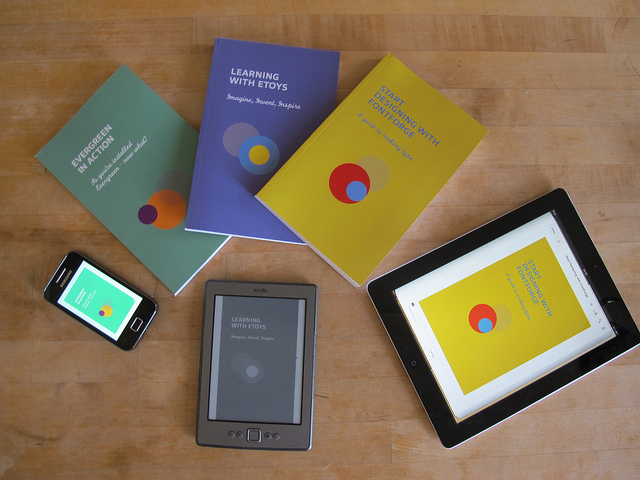

These three books were created in a three-day Book Sprint and output to paper, MOBI and EPUB on the third day.

These three books were created in a three-day Book Sprint and output to paper, MOBI and EPUB on the third day.

Book Sprints bring together 4-12 people to work in an intensely collaborative way, going from zero to book in 3-5 days. There is no pre-production and the group is guided by a facilitator from zero-to-published book in the time available. The books produced are made available immediately at the end of the sprint in print (using print-on-demand services) and ebook formats. Books Sprints produce great books and they are a great learning environment and team-building process.

This kind of spectacular efficiency can only occur because of intense collaboration, facilitation and synchronous shared production environments. Forget mailing MS Word files around and recording changes. This is a different process entirely. Think contributors and facilitators, not authors and editors.

There are five main parts of a Book Sprint (thanks to Dr D. Berry and M. Dieter for articulating the following so succinctly):

- Concept Mapping: development of themes, concepts, ideas, developing ownership, and so on.

- Structuring: creating chapter headings, dividing the work, scoping the book (in Booktype, for example).

- Writing: distributing sections/chapters, writing and discussion, but mostly writing (into Booktype, for example).

- Composition: iterative process of re-structure, checking, discussing, copy editing, and proofing.

- Publication

The emphasis is on ‘here and now’ production and the facilitator’s role is to manage interpersonal dynamics and production requirements through these phases (illustration and creation of other content types can take place along this timeline and following similar phases).

Since founding the Book Sprints method four years ago, I have refined the methodology greatly and facilitated more than 50 Book Sprints – each wildly different from the other. There have been sprints about software, activism, oil contract transparency, collaboration, workspaces, marketing, training materials, open spending data, notation systems, Internet security, making fonts, OER, art theory and many other topics.

People love participating in Book Sprints, partly because at the end of a fixed time they have been part of something special – making a book – but they are also amazed at the quality of the books made and proud of their achievement. The Book Sprints process releases them from the extended timelines (and burdens of guilt) required to produce single-authored works.

Here are some interestingwrite-upss that provide more detail on the process:

http://techblog.safaribooksonline.com/2012/12/13/0-to-book-in-3-days/

http://google-opensource.blogspot.com/2013/01/google-document-sprint-2012-3-more.html

http://www.booksprints.net/2012/09/everything-you-wanted-to-know/

Originally published on O’Reilly, 28 Jan 2013 http://toc.oreilly.com/2013/01/zero-to-book-in-three-days.html