Some of my projects. As you can see, partially complete. Will add more and then make this a static page.

Publishing-related

Collaborative Knowledge Foundation

Current

The Collaborative Knowledge Foundation’s mission is to evolve how scholarship is created, produced and reported. CKF is building open source solutions in scholarly knowledge production that foster collaboration, integrity and speed.

CKF envisions a new research communication ecosystem that gives rise to wholly unique channels for research output.

CKF was founded in October 2015 with support from the Shuttleworth Foundation.

Shuttleworth Foundation

Current

I have just been awarded a Shuttleworth Foundation Fellowship. I’m deeply honoured to have been selected. I was awarded a second year of Shuttleworth Fellowship for my work on reformulating how knowledge is produced.

Recent Presentations

The Future of Text

Google Headquarters in Silicon Valley, Aug 2016

http://www.thefutureoftext.org/

Organised by friends and followers of Douglas Englebart, Adam was invited to present on collaboration and book production.

Association of Learned and Professional Society Publishers

London, Sept 2016

http://www.alpsp.org/2016-Programme

Adam was invited to present at the annual ALPSP conference about ways that Open Source could change publishing.

International Society of Managing & Technical Editors

Brussels, Nov 2016

http://www.ismte.org/page/2016EuroConference

http://www.slides.com/eset/ismte

Adam was invited to present on Open Source tools for publishers at the Brussels edition of the 2016 IMSTE series of conferences.

Open Fields

Riga, Latvia, Oct 2016

http://rixc.org/en/festival/Open%20Fields%20Konference/

I was invited to speak about the intersection of art, science, and publishing at the cutting edge Open Fields festival.

Unlearning Collaboration

Berlin, Oct 2016

http://www.supermarkt-berlin.net/event/un-learning-networked-collaboration/

Adam was invited to facilitate a one day conference on collaboration and facilitation.

Development projects

PagedMedia

2016 – present

http://wwwpagedmedia.org

Founded the blog about paged media.

Substance Consortium

2016 – present

http://substance.io/consortium/

Foundational member of the Substance Consortium.

Book Sprints

2008 – present, New Zealand

http://www.booksprints.net/

Book Sprints is a methodology and a company I founded to rapidly produce books.

Nov 2016: transitioned from founder and CEO to the board. I appointed Barbara Rühling as CEO.

A Book Sprint is a collaborative process where a book is produced from the ground up in just five days. But even more important, this collaborative process captures the knowledge of a group of subject-matter experts in a manner that would be nearly impossible using traditional methods. The result at the end of the Book Sprint is a high-quality finished book in digital and print-ready formats, ready for distribution.

Book Sprints Ltd, is a team of facilitators, book-production professionals, and illustrators specialised in Book Sprint facilitation and rapid book production. Our organisation developed the original methodology and has refined it since 2008 through the facilitation of more than 100 Book Sprints. Topics have ranged from corporate documentation to industry guides, government policies, technical documentation, white papers, academic research papers, and activist manuals.

Book Sprints clients include Cisco, PLOS, F5, the World Bank, USAID, African Development Bank, Open Oil, Liturgical Press, Ausburg Fortress, Cryptoparty, OpenStack, European Commission, JISC CETIS, UNECA, Mozilla, IDEA, Engine Room, Heidy Collective, Transmediale, Google… to name a few.

"If Book Sprints did not exist, we would be forced to invent them, so powerful is the knowledge production paradigm." --Allen Gunn, Aspiration "Book Sprints get more brilliant work out of bright people in 1 week than most project can evoke across many months." --Loy Evans, Cisco "Writing a book through a Book Sprint turned out to be efficient, thorough and enjoyable; I can’t imagine a better outcome." --Phil Barker, JISC CETIS

Aperta

2013 – July 2015. Public Libary of Science, San Francisco

In 2013, I designed a platform for the Public Library of Science (PLOS), originally called Tahi but renamed to Aperta. In 2014 I was asked to lead a team to build the platform. I led the 15 strong team to the production-ready 1.0 release of this multi-million dollar project to completion, on time and under budget in June 2015.

Aperta is an entire submission and peer review platform for multiple scientific journals housed within the single instance. The entire system is designed to be highly collaborative and concurrent. The platform includes a manuscript production interface, HTML and LaTeX document editing support, Word ingestion, a workflow management system, task management interfaces, admin interfaces, reports, and user dashboards. The platform was built in Ember-CLI, Rails, implements a highly customised Wikimedia Foundations Visual Editor, and uses Slanger for concurrency. It is an HTML-first system, has many innovative new approaches to journal systems, and solved many long-standing problems in this space. The project also involved a separate codebase named iHat that provides Aperta with an API service for queue-managed file conversions.

"At its core, this new PLOS editorial environment brings simplicity to the submission and peer review process by providing advanced task-management technology and a vastly improved user interface, which will enhance the publishing experience for our community of authors, editors, and reviewers." http://blogs.plos.org/plos/2015/07/publishing-initiatives-at-plos-a-look-back-and-a-look-ahead/

NB: I only work on Open Source systems. The sources are not yet available for this project.

PubSweet

2012 – present

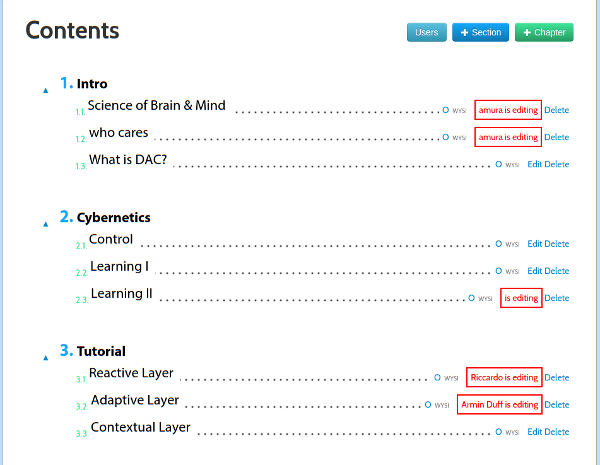

PubSweet is a platform designed to assist the rapid production of books in Book Sprints. The platform is very simple to use, with very little overhead for new users. The system provides dashboards, publishing consoles, card-based workflow management (task manager), discussions, data visualisations of contributions, a dynamic table of content management, and support for multiple chapter types. PubSweet can produce EPUB and leverages book.js (see below) to produce print-ready PDF (paginated in the browser). PubSweet is written in PHP, using Node on the backend, and CKEditor as the content editor.

Lexicon

2012

Lexicon is a platform produced for the United Nations Development Project to collaboratively produce a tri-lingual (Arabic, French, English) lexicon of electoral terms for distribution in Arabic regions. Lexicon provided concurrent editing for chapters with multiple terms, sorting by language, discussion forums and voting. Lexicon was written quickly in php with Node.

"The Lexicon was created with the aid of an innovative collaborative writing tool customized to suit the needs of this project. This web-based software allowed the authors, reviewers, translators and editors to simultaneously input their contributions to successive drafts from their various countries. "http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2014/11/19/undp-launches-first-lexicon-of-electoral-terminology-in-three-languages.html

![]()

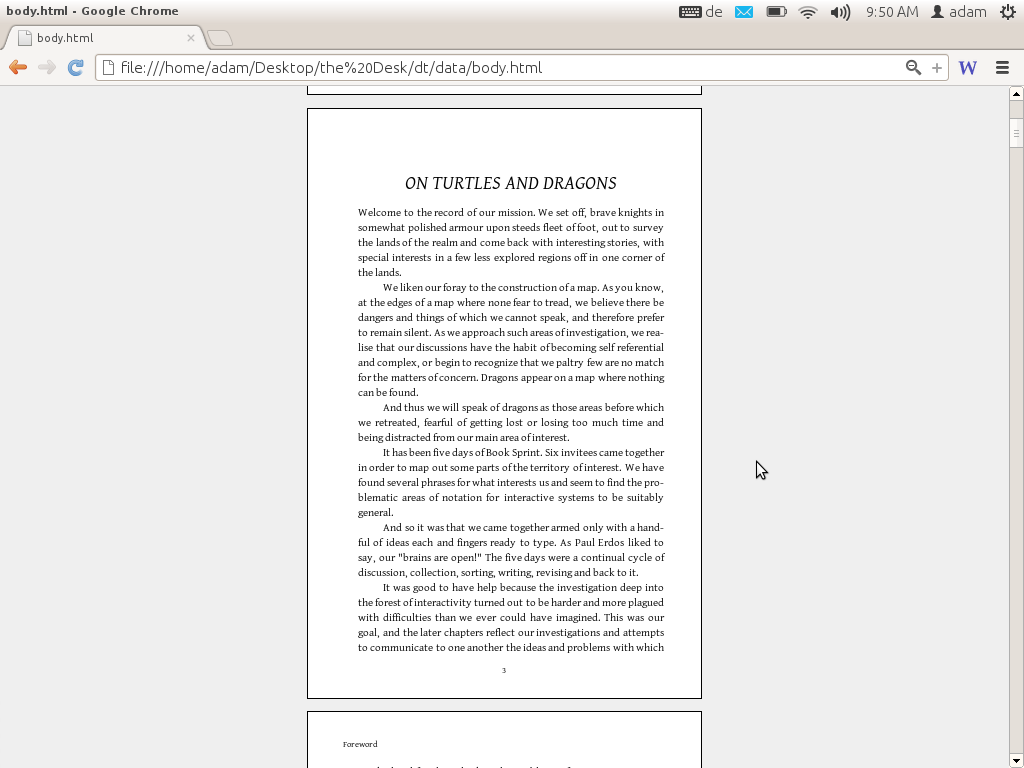

book.js

2012

book.js is a Javascript library that you can use to turn a web page into a PDF formatted for printing as a book. Take a web page, add the JavaScript, and you will see the page transformed into a paginated book complete with page breaks, margins, page numbers, table of contents, front matter, headers etc. When you print that page you have a book-formatted PDF ready to print.

book.js has given inspiration to a number of other JS pagination engines. See Vivliostyle, bookJS Polyfil, Pagination.js, simplePagination.js, and CaSSiuS.

Booktype

2010 / 2012

Booktype is a book production platform. I brought this platform to Sourcefabric (Berlin) as ‘Booki’ in 2012. Booki was started in 2010. Booktype is written in Python (Django).

“Booktype resolves challenging issues in collaborative knowledge production resulting in high quality print and ebooks.” – Erik Möller, deputy director, Wikimedia Foundation

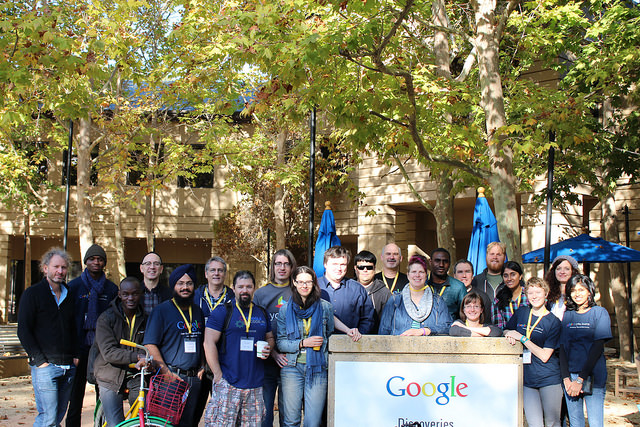

Google Summer of Docs

2011, 2012, 2013

The GSoC Doc Camp was an annual event over three years. It was a place for documenters to meet, work on documentation, and share their documentation experiences. The camp improved free documentation materials and skills in GSoC projects and helped form the identity of the emergent free-documentation sector.

The Doc Camp consisted of 2 major components – an unconference and 3-5 short form Book Sprints to produce ‘Quick Start’ guides for specific GSoC projects.

Each Quick Start Sprint brought together 5-8 individuals to produce a book on a specific GSoC project. The Quick Start books were launched at the opening party for the GSoC Mentors’ Summit immediately following the event.

Bookimobile

2011

The Bookimobile was a a mobile print lab in a van – essentially a van that contained all the equipment necessary to create perfect bound books. It was designed to take the ideas of Booki to people and make real books that have been created in Booki. The first Bookimobile was based on the Internet Archives Book Mobile and we took it to several book fairs and events throughout Europe. It was sponsored by Mozilla, CiviCRM, Archive.org, Francophonie.org, Google Summer of Code, and iCommons.

Objavi

2008

Objavi is an API-software service originally written for Twiki Book (see below) but also serviced Booki and later Booktype. Objavi converts books from their native HTML into PDF for printing. It also handled other file conversions (eg HTML to ODT, HTML to EPUB etc). I later produced a similar API-based conversion software for PLOS known as iHat. Objavi is written in Python.

TWiki Book

2006

TWiki Book didn’t have a real project name at the time. The project was the first publishing system I built. TWiki Books was created solely to meet the needs of FLOSS Manuals (see below) and it was built on top of TWiki, a Perl-based wiki. TWiki Book included book remixing features, side by side translation, table of contents building, publishing interfaces (I actually wrote a separate php-based system to manage this), edit notifications, versioning, diffs, live chats and many other features. It was a good system but reasonably difficult to extend and maintain since it re-purposed an existing wiki software (hence my approach to building purpose-built book production systems after this point).

FLOSS Manuals

2006

FLOSS Manuals was the project I founded in 2006 that got me started on this whole publishing thing. FM was, and is still, an active community of volunteers that creates free manuals about free software. There is now a foundation and several language communities (notably French and English). The contributors include designers, readers, writers, illustrators, free software fans, editors, artists, software developers, activists, and many others. Anyone can contribute to a manual – to fix a spelling mistake, add a more detailed explanation, write a new chapter, or start a whole new manual on a topic. The aim was produce high quality free works and we succeeded – creating many fantastic manuals in over 30 languages (and still growing).

“Introduction to the Command Line” is at least as clear, complete, and accurate as any I’ve read or written. But while there are countless correct reference works on the subject, FLOSS’s book speaks to an audience of absolute beginners more effectively, and is ultimately more useful, than any other I have seen.” -- Benjamin Mako Hill, Wikimedia Foundation Advisory Board, Free Software Foundation Board

Presentations about publishing

I am asked to talk about publishing from time to time. The following are some links to some of those presentations.

Choosing a document network

August 2015, Vancouver, Public Knowledge Project

Open Access and Open Standards

Oct 2014, San Francisco, Books in Browsers

May 2014, Rotterdam, Off the Press

May 2014, San Francisco, I Annotate

May 2013, San Francisco, I Annotate

Oct 2013, San Francisco, Books in Browsers

May 2012, Berlin, re:publica

Writings

I have been writing about publishing here and there. Since last year these efforts have been focused on this site. The following are some links to some of my other works:

Fantasies of the Library : After the Proprietary Model

Interview with me about the future models for publishing, published by k-verlag (Berlin).

Radar O’Reilly posts

When Paper Fails

What happens when books, ownership, authority and authors are all challenged by a network.

Visualizing Book Production

Why is no one visualising data on how we make books?

Zero to Book in 3 Days

A little bit about Book Sprints.

Forking the Book

When books are forked.

Over Thinking EPUB

Commentary on why EPUB might be confusing the issue.

Changing the Culture of Production

How to change the way we produce knowledge.

WYSIWYG vs WYSI

The evolution of the editor.

Math Typesetting

the sorry state of math typesetting.

InDesign vs CSS

Why HTML wins versus Desktop Apps.

The Blanche Dubois Economy

Why ‘Open API’ is really a silly idea.

Gutenberg Regions

Paginating in the browser.

Browser as Typesetting Engine

More commentary on the browser as a typeset engine.

The New New Typography

The evolution of Javascript Typesetting.

Other Projects

Seaweed

2008, Quarantine Island, New Zealand

This project was actually called ‘Intertidal’ but I like the name Seaweed better. Douglas Bagnall and I created a one-day community project to discover a new species of seaweed. We hosted this on Quaratine Island in the Dunedin Harbour and invited anyone to come work with us and a marine biologist from the local research center to search for a new species. The project was a community project and a reflection on the notions of species as an out-moded idea, and on taxonomy as a dying art. About 50 or 60 people – individuals, groups, and families – came out on the free boat (provided by the local sea scouts) and hiked across the island to participate on a coldish Dunedin day to search for and document seaweed. We possibly discovered a new species.

throwing into focus the ever-present potential for new knowledge. Drawing upon 19th century methods of species discovery, involving collecting, looking and drawing, their work formed questions around what we don't know.

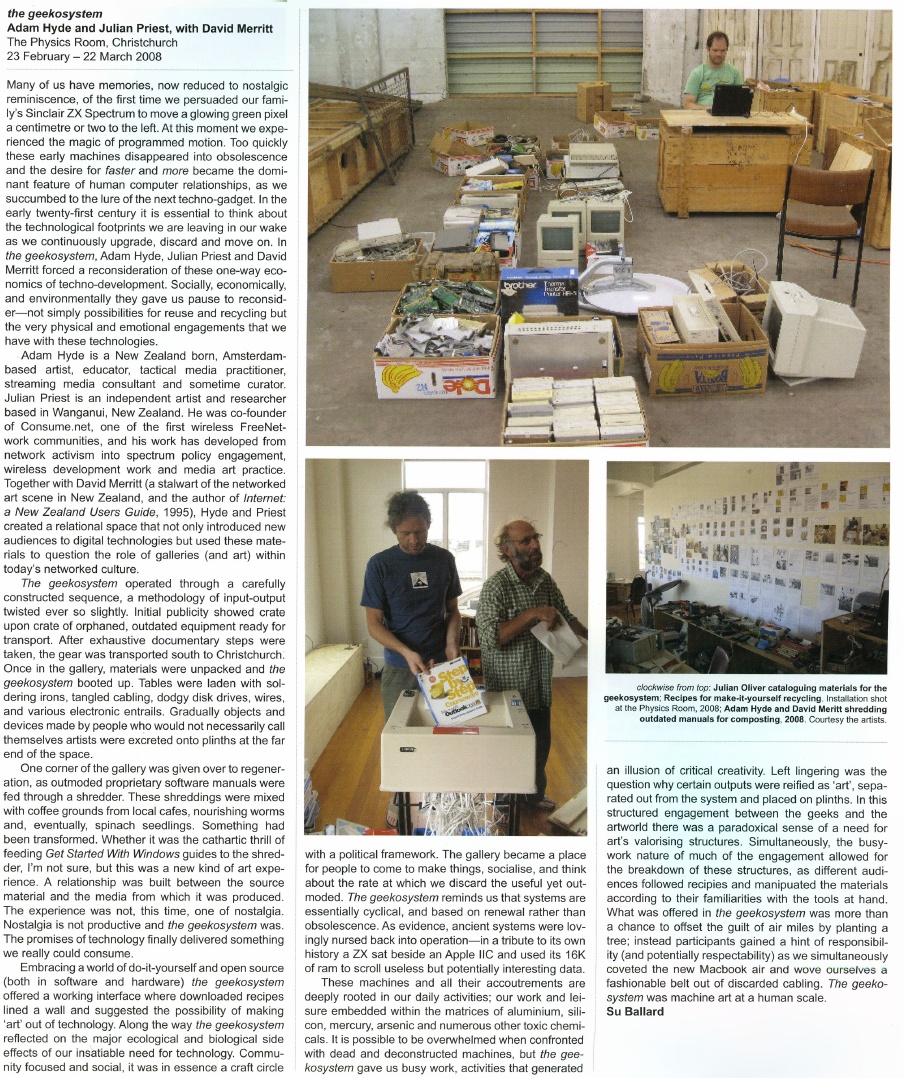

Geek-o-system

2008, Christchurch, New Zealand

Julian Priest, Dave Merritt and I drove about a tonne of old electronics 700km or so in an old landrover (top speed 35km/hr) from Daves warehouse in Wanganui to an art gallery in Christchurch, New Zealand. In the gallery, we served up the old electronics as a participatory art project and invited anyone to come and build new objects from the old. It took 3 days to get there. It was an adventure.

A Geekosystem was a participatory workshop based on a redundant technology collection created by David Merritt. Items were selected from the collection and packed into a Landrover and driven to The Physics Room in Christchurch. A call for participation was issued by The Physics Room and a group of geeks gathered to re-configure the technology into artworks. A workshop space was created and plinths were placed at once end of the gallery and populated with artworks made from the e-waste. The workshop was open to the public and continually added to during the duration of the show. Old technology books were formed into a library. Proprietary software manuals were shredded and mixed with coffee grounds. This was mulched into soil and silver beet seedlings were successfully germniated in floppy disk trays.

A Geekosystem was shown first at the Physics Room in Christchurch in 2008 and then at The Green Bench during the Whanganui Open studio week in 2008. The Geekosystem garden was transferred to a permanent location and produced vegetables for a number of years.

Paper Cup Telephone Network

2006, Exhibited at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, Zero One Festival in San Jose, and many other venues.

This was a project I made with Matthew Biederman and Lotte Meijer. The Paper Cup Telephone Network (PCTN) was a free communication system and comment on how ‘simplicity’ in technical systems is trickery, and problematising the corporatisation and ever increasing individualisation of modern communications.

The PCTN was a network of paper cup telephones. Just like the games played by children, anyone could put a PCTN cup to their ear to listen, or to their mouth to speak. However, the difference between the PCTN and the original game is that the “string” is connected to the World Wide Web where your voice is streamed to all the cups on the network carrying it, blocks or even miles or a continent away. We built the entire system from free software telephony systems (asterisk and SIP phones), open and standards-based telephony protocols, cups, and string.

As simple as it was, it remains the most difficult technical project I have ever undertaken.

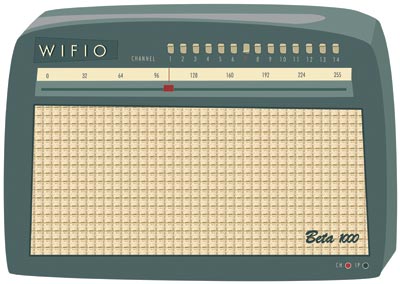

Wifio

2006, exhibited at the Waves exhibition in Riga, Latvia

Wifio was a project I did with Lotte Meijer and Aleksandar Erkalovic. Wifio was a comment on the naivety in which we broadcast our personal information. It was a hardware UI and software that allowed anyone to tune into the World Wide Web wifi traffic. If someone near you was browsing the web on a wifi network, you could simply tune in with Wifio by selecting the right channel and tuning into their IP address.

…but don’t worry, you don’t need to know what their “IP Address” is, in fact you don’t even need to know what an IP address is! Just move the dial until you hear their emails or what they are saying in chatrooms.

I was proud when Julian Oliver (an old buddy from NZ) referenced this project as inspiration for one of his works.

Sound Elevator

2007

r a d i o q u a l i a (see below) were commissioned to make a new work for Forte di Bard in Valle d’Aosta in Italy for “Cima alle stelle (Stars)”, a large exhibition showing historical works by major masters like Durer, Tintoretto and Guercino; contemporary artists such as Pierre Huygue, Olafur Eliasson and others; and astronomical instruments and writings by Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Newton and Einstein.

We made a new site-specific sound installation inside two of the glass elevators which take visitors from the arrival area of Forte di Bard, to the gallery levels. Much of the elevator travel is external to the Forte (pictured below). Sound Elevator consisted of two linked sound environments inside the elevators. As the elevators ascended to the exhibitions halls, visitors experienced an auditory journey from the local celestial environment to the edges of the Universe. In the first elevator, visitors sonically travelled through the Earth’s ionosphere and magnetosphere, hearing our closest star, the Sun, interacting with our planetary atmosphere. The upward and outward journey continued in the second elevator, with sounds from our planetary neighbours, the sonic echo of distant stars, and finally the sound of the Big Bang itself.

I-TASC

2006/2007 Antarctica

I did a 2-month residency in Antarctica at SANAE (South African Research Base) as part of I-TASC, ultimately a failed network of individuals and organisations working collaboratively in the fields of art, engineering, science and technology on the interdisciplinary development and tactical deployment of renewable energy, waste recycling systems, sustainable architecture and open-format, open-source media. But it was still a great experience.

The coolest thing about it, was the 2 weeks each way on the beautiful icebreaker the SA Agulhas (now decommissioned). I kept some diary pages on the Interpolar site. I also did a few other projects while there including Polar Radio (see below).

The worst thing about it was that we shouldn’t have been there. There is no need for anyone to be in Antarctica. Most of the ‘science’ projects are strategic positioning for a land grab when the time comes. Some science might be justifiable… but arts projects?

Leaving Antarctica I cried my eyes out. It was just too much for me to deal with. Too amazing. After Antarctica, I gave up the art world. I couldn’t think of anything else the art world could do for me.

It was a conflicted but beautiful experience.

Polar Radio

2006/2007, Antartica

Polar Radio was a community radio project initiated by I-TASC and

r a d i o q u a l i a. The first prototype station began FM broadcasts on 29 December 2006 in the Dronning Maud Land sector of Antarctica, where South Africa maintains their base, SANAE IV. It was Antarctica’s first artist-run radio station. It was the first step towards establishing a permanent polar radio presence in Antarctica, which may eventually broadcast in between geographically dispersed Antarctic bases.

But y’know…I wish I hadn’t done it. When I first got to Antarctica I turned on a radio and went through many many frequencies… and I heard nothing… that was amazing. Where else in the world can you not hear anything on your radio? I then went ahead and polluted the spectrum. Darn. I regret it.

Polar Radio was part of a series of projects run by I-TASC – the Interpolar Transnational Art Science Constellation.

Mobicast

2005, Transiberian Express

Capturing the Moving Mind was a conference on board the Trans-Siberian train. It was about new forms of movement and control, war and economy, in the current situation. 50 international researchers, artists and activists participating in the mobile conference formed a mobile production unit aboard the train. For the audiovisual streams, Luka Princic and I developed a free software ‘mobicasting’ platform which enabled mobile transmission of material on the web from mobile phones on the train. Mobicast was initially developed during a residency I had at MAMA Media Lab (Zagreb, Croatia).

It was a great project but really really fragile. The tech of the time was not up to it. Mostly it ran on Puredata and some obscure bits of code from here and there. Still it worked. Best moments were hanging out on the train laughing at people trying to be ‘artists’ in real time… huh? …and getting sardonic with Dr Gillian Fuller – the world’s best queue hacker. Watching the train wind around the Gobi desert… also kinda cool.

mobicast was initially developed to overcome the problem of delivering live video from a moving train to the internet. Traditionally this is the domain of OB (Outside Broadcast) technologies or expensive vehicular satellite uplink hardware. However mobile phones are now very capable remote broadcast environments. Many modern phones record images, video, audio and allow the editing and transfer of these media through wireless data networks (eg. GPRS) with almost global coverage. The quality of these recorded media have generally been considered 'low-fi' but fidelity is increasing and importantly, the expectations of networked media are becoming more appropriate. Once upon a time there was a mythic "broadcast quality" threshold all media had to pass before being accepted by broadcast organisations and (theoretically) audiences. However, now there are active calls for content generated by "on the spot" accidental observers by large scale media organisations. The tide and scale of remote media is changing. The nature of experimental media on this type of platform is the intentional playground of mobicasting. With this emerging new type of media witness cultural forms are also emerging. Multiple networked media phones is in itself a platform for collaborative cultural development and opens interesting doors for experimental media.

MiniFM and SilentTV

2001-2004, International

For many years I had a wonderful mentor – Tetsuo Kogawa. He is the father of MiniFM. I saw Tetsuo build a mini FM transmitter at the Next Five Minutes festival in Amsterdam. Sometime after that, I asked him if he would teach me how to make them too, and he very generously spent a good deal of time making sure I understood the ins-and-outs of the process. Together we designed a workshop and Tetsuo worked out even simpler ways to build the transmitters. For many years I travelled the world leading transmitter-building workshops and often Tetsuo would stream in from his studio in Tokyo to talk about the idea and give a quick demonstration before we started building.

Later Tetsuo and I created a project called SilentTV which was the same idea but using simple elements to broadcast TV.

I’m forever grateful to Tetsuo for his kindness and mentorship.

re:Play

November 2003, South Africa

re:Play explored the world of the computer game. It featured an exhibition of artists’ computer games by Andy Deck, Josh On + Futurefarmers, Mongrel, Natalie Bookchin, the escapefromwoomera collective and Max Barry, and a programme of workshops and lectures. re:Play was a collaboration between the Institute for Contemporary Art, Cape Town and r a d i o q u a l i a. It launched at L/B’s – The Lounge at Jo’Burg Bar in central Cape Town, South Africa, and went on to be exhibited at Artspace and the Physics Room in New Zealand.

The games in the exhibition were not typical computer games. While all of them encouraged play, and involved a gaming objective, unlike regular computer games, they had a strong political dimension and explored how play, interaction and competition can be utilised in an artistic context.

The re:Play education programme included talks and workshops lead by Graham Harwood of Mongrel and r a d i o q u a l i a at Cape Town High School, Fezeka Senior Secondary School in Gugulethu; the Alexandra Renewal Project, Johannesburg and at Wits School of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

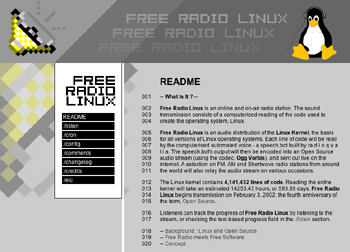

Free Radio Linux

2002, The World

Another project that got a lot of attention for r a d i o q u a l i a, most notably through being exhibited at the New Museum in NYC, but it also at Banff and other places. I loved this project because it brought together several threads.

Formally, Free Radio Linux was an online and on-air radio station. The sound transmission was a computerised reading of the entire source code used to create the Linux Kernel, the basis of all distributions of Linux.

Each line of code was read by an automated computer voice – a speech.bot

utility I built for the work. The speech.bot’s output was encoded

into an audio stream, using the early open source audio codec, Ogg Vorbis, and was broadcast live on the internet. FM, AM and Shortwave radio stations from around the world also relayed the audio stream on various occasions.

The Linux kernel at that time had 4,141,432 millions lines of code. Reading the entire kernel took an estimated 14253.43 hours, or 593.89 days.

Listeners tracked the progress of Free Radio Linux by listening to the

audio stream, or checking the text-based progress field in the ./listen

section of the website (which is no longer up)…

Essentially this was all about how free radio and free software were wierdly the same. If you ever worked with free radio geeks, you will know they are nerdy technophiles who believe in the purity of what they are doing. Very much the same as Open Source geeks at the time. Most were interested in the tech and the political ideal of the respective mediums (radio and software). So, FRL was a comment on this. It was also a comment on how free radio was, ironically, very difficult to achieve on the internet unless serious attention was made to developing free codecs. But also FRL had two other elements going for it. The first was to (again) poke fun at the ridiculous hyperbole that surrounded the open source movement. People were expounding this ‘amazing new phenomenon’ and extrapolating how it would change the world (much as they did about wikis a short time after) when they had never come into contact with code or geeks. So this was an attempt to expose those people to the code…or what it sounded like. But also, at the time there was a lot of early talk about how to preserve digital media (a problem still not solved) and radio waves apparently never die… so by broadcasting the Linux kernel into space we were preserving it on the oldest medium ever, forever. Hehe…

I did, however, feel very sorry for the attendants at the New Museum who had to work 8-hour shifts listening to “one dollar sign dollar sign comma hatch four new line seven two dollar sign dollar sign…”

Thing FM

2002, New York City

This was, in theory, a radio network but in reality, just a few transmitters got installed. Still, it was fun. Thing FM was based in NYC and built during a residency I did at the Thing in NYC. The same week that the Yes Men came into the office to film their ‘shit burger’ stunt. They came into the Thing and asked who wanted to go and I didn’t go! doh! Anyway, we built the network using internet audio (via wireless and wired connections) and miniFM. Each of the transmitters was about 0.1 W output and sourced their audio live from the internet using the Frequency Clock scheduling system I had built earlier.

This partly adopts the ethic of micro-radio as founded by Tetsuo Kogawa, where many low powered FM transmitters are coupled to create an effective broadcasting entity that ‘falls beneath the radar’ of the communication authorities. fm.thing.net combined this ethic with that of net.radio which was a relatively new phenomenon focusing on the use of the internet as a carrier signal, best illustrated by the practices of the Xchange network. By combining the net.radio and micro-radio we hoped to build an efficient radio network in New York that used the internet as a primary carrier of the audio for re-broadcasting on legal or almost legal microFM broadcasts.

Hanging with Ted Byfield and Jan Gerber was a highlight of this experience. Wolfgang Strauss was also pretty fun but I was so intimidated by him. He was just so cool. Also sharing a tenement apartment in Ludlow Street with 3 people (bath in the kitchen) was pretty fun.

Radio Astronomy

2001

Radio Astronomy was an art and science project which broadcasts sounds intercepted from space, live on the internet and on the airwaves. The project was a collaboration between r a d i o q u a l i a, and radio telescopes located throughout the world. Together we were creating ‘radio astronomy’ in the literal sense – a radio station devoted to broadcasting audio from our cosmos.

Radio Astronomy had three parts:

- a sound installation

- a live on-air radio transmission

- a live online radio broadcast

Listeners heard the acoustic output of radio telescopes live. The content of the live transmission depended on the objects being observed by partner telescopes. On any given occasion, listeners may have heard the planet Jupiter and its interaction with its moons, radiation from the Sun, activity from far-off pulsars or other astronomical phenomena. Honor from rQ later made a TED Talk about it.

Dino, drummer from HDU, did the website design…thats gotta rate…

RT32

2001, Latvia

In 2001 I had the good fortune to be part of the Acoustic.Space.Lab project which started a long love affair with the RT32 radio telescope. Formerly a cold war device, this telescope was liberated when the Russian Army pulled out of Latvia. I worked with this telescope as an artistic device and with the generous scientists for many years after. The doco clip below introduces the explorations of the international Acoustic Space Lab Symposium which took place on the site of RT-32 in 2001.

Highlights of this period in Latvia included being evicted by Russian builders, getting a hernia, and being amazed Marc Tuters survived eating so many dodgy looking mushrooms he found in the forest.

Open Sauces

May 2001, Scotland and also later…

I have come to realise there is just too much stuff I have tinkered with to comment on. Open Sauces falls into that bucket. Google tells me this was 2001. Essentially I got sick of all the Open Source blah blah of the time.. everything was suffixed by OPEN and it got very tiring (Open Gov, Open Hardware, Open Society…). No critical reflection on the fact that geek methods are geek methods and they are not transportable – AND – OPEN processes, methods etc existed well before geeks came along and inherited the word. No geek invented openness. I’m still tired of this I have to say…still…. I created Open Sauces which was an open database of recipes… anyone that did a residency could add their favourite recipe and you could just tick all the ingredients you have in your fridge and get a recipe to suit… doesn’t sound too revolutionary but at the time this sort of thing didn’t exist. It was a comment on this abuse of the use of the word ‘open’ and how cooking way preceded sharing of ‘code’ / ‘instructions’ etc… and also how food is probably the most important part of any collaborative project, whereas unsocial nerdy talk is optional. Later Fo.am in Brussels were inspired by the idea and started an Open Sauces theme.

net.congestion

2000, Amsterdam

I’m particularly proud of this project. It came about when I was a very naive newly arrived resident of Amsterdam. I suggested to Geert Lovink this idea for a festival and he said to speak to Erik Kluitenberg. Both huge legends in my mind you understand… I mustered the courage up to suggest it to Erik who was a cultural curator at De Balie at the time. He said he would think about it and I thought I wasn’t very convincing. A week later he called me up and said let’s do it! Whoot!

The festival was held in Amsterdam in October 2000. Net.congestion was an intensive three-day celebration and critique of the new cultures that have arisen from all forms of micro-, narrow- and broad- casting via the internet, now collectively known as streaming media.

The event covered most of the interesting ground of the time for streaming media, from the transformation of issues surrounding intellectual property to the uses of streaming as a mobilisation tool for global resistance through to the more rarefied questions of aesthetics and how narratives are transformed when embedded in networks. The overwhelming experience of many visitors to Net.congestion was a sense of tools, networks and sensibilities being re-purposed, returning us, again and again, to a primary experience of the net as a social space.

Net.congestion occurred just months before dot.com bubble burst, exploding the ‘new economy’ and ‘the long boom’ with its fantasies of a world in which the economic laws of gravity had been repealed. There is no doubt that if the same event were to be held now, the atmosphere would be markedly different. It is not that Net.congestion was an industry event which depended on the hype for its existence, as the very title indicates that we mixed a healthy dose of skepticism with our festivities. But none of us, however critical, can entirely escape the zeitgeist and there is no doubt that in those brief heady days Warhol’s aphorism was re-written; we could all dream of becoming billionaires, if only for 15 minutes. A strange historical phase when (particularly for anyone involved in streaming media) the normally fixed boundaries between business, art, technology, science fantasy and just plain bullshit temporarily blurred to create a moment of unique cultural hysteria. In that sense our timing was perfect.

The Theory Machine

2000

In an attempt to make theorists a little more funky, I made a software they could use to put their brainy thoughts to glitchy syncopation. It was mainly used by Eric Kluitenberg including one memorable performance at Club Otok in Dubrovnik.

HelpB92

1999, Amsterdam

I helped found an organisation during the Nato bombing of Serbia and Kosovo in 1999. The international support campaign for independent media in Yugoslavia, including the famous Radio B92 media centre, in operation between March and July 1999. We did some pretty cool things but mostly I was very happy to be involved in what must have been one of the web’s early large-scale activist campaigns. It was also the start of my longish relationship with Amsterdam as XS4ALL offered me a job and I stayed for a few years. I still have a bike there somewhere.

What was tricky, though, is that I agreed to go to Skopje to assist an Albanian refugee radio station (Radio 21). It was kinda nerve wracking. There were literally bombs set to explode to take out as many Albanians as possible. Some kids lost their legs across the street from where I was working. I was a milk and cookies boy from NZ.. what was I doing here? Still, I stuck it out and we managed to set up quite an innovative way of getting radio transmissions out of the refugee camps to Radio Netherlands Shortwave.. .I’ll write that up when I get time.

The Frequency Clock

1998 – 2004 or so, The World

This was one of the earliest r a d i o q u a l i a projects and how I learned to program. To understand this project you have to understand the dark ages of the internet when video and audio hardly existed. Essentially we built a media scheduling system that allowed you to build archives of live and pre-recorded content, tag them, and then schedule them. All built in JavaScript… remembering these were these days when Javascript was very rudimentary.

The Frequency Clock was originally conceived as a mechanism to control FM transmitters over the internet. In essence it was a networked timetabling system, connecting globally dispersed FM transmitters so they could broadcast the same internet audio simultaneously. The original player was a popup window but we also built desktop apps to do the same thing using VisualBasic (Win) and RealBasic (Mac). All open source.

However… then we realised that video could also work… and we used it to control community TV channels in Amsterdam and Linz and we also controlled giant video billboards in Estonia and a whole lot of other things. It was exibited a lot, most notably at the Walker when Steve Dietz was still there. We even installed a transmitter in the roof of De Waag! It was a remarkable experiment for its time. Yes, yes, pre-Napster and YouTube and all those other toys… while writing this I found some kind of prototype online.

Sound Performances

1996 – 2008, the world.

Performing solo as ‘eset’ and with Honor Harger as r a d i o q u a l i a I did a lot of sound performances, most using sounds from space and either live performances in real space or on radio. Some stuff still exists online:

https://soundcloud.com/radioqualia

Or eg:

r a d i o q u a l i a

This was the project that liberated me from the south and the reason I moved to Europe with no money and no return ticket. My plan was to make coffee and do some arty stuff in London. Thankfully, Nato bombed Serbia (hoho) and everything changed.

What I really loved about this time, was that I felt part of a lovely international community of artists. We used to travel around and bump into each other in various crazy places. This group included people like Marko Pelijhan, Heath Bunting, Rachel Baker, James Stevens, Luka Frelih, the Mama crew, Lev Manovich, Steven Kovats, Matthew Beiderman, Giovanni D’Angelo, Zita Joyce, Adam Willetts, Rasa Smits, Raitis Smits and so many many others…it was an awesome time.

r a d i o q u a l i a was an artist project that consisted of myself and Honor Harger. I have described some of our exhibitions and performance projects above, and listed some below. There were many more.

In August 2004, r a d i o q u a l i a was awarded a UNESCO Digital Art Prize for the project Radio Astronomy. In September 2003, we were awarded the Leonardo-@rt Outsiders 2003 New Horizons Prize together with the participants of the Open Sky installation at the @rt Outsiders exhibition at the Museum of European Photography in Paris.

Selected r a d i o q u a l i a exhibitions and performances:

Lecture & performance at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Work: Sonifying Space, as part of the Space Art conference

Exhibition at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, USA

Work: Free Radio Linux, as part of the OpenSourceArt_Hack exhibition

Exhibition at the NTT InterCommunication Centre, Tokyo, Japan

Work: Radio Astronomy, as part of open nature, a show curated by Yukiko Shikata

Online exhibition / commission / installation at Gallery 9, Walker Art Centre, USA

Work: Free Radio Linux

Exhibition at Arsenals Exhibition Hall, Riga, Latvia

Work: solar listening_stations, part of WAVES

Exhibition at HMKV, Dortmund, Germany

Work: solar listening_stations, part of Solar Radio Station

Exhibition at the Walter Philips Gallery, Banff, Canada

Work: Free Radio Linux, as part of The Art Formerly Known As New Media

Exhibition at Centre d’Art Santa Monica, Barcelona, Spain

Work: Radio Astronomy, as part of Sonar 2005

Performance at Tesla, Berlin, Germany

Work: from polar radio to solar wind

Performance, La Batie Festival, Geneva, Switzerland

Work: signals as part of signal-sever

Exhibition at Ars Electronica, Linz

Work: Radio Astronomy

Exhibition at ISEA 2004, Helsinki, Finland

Work: Radio Astronomy

Symposium & Performance, Ventspils International Radio Astronomy Centre, Latvia

Work: Acoustic Space: RT32: Orchestrating the Solar System

Broadcast on Radio New Zealand

Work: Revolutions Per Minute 1: Frequency Shifting Paradigms in Broadcast Audio

Broadcast on Radio New Zealand

Work: Revolutions Per Minute 2: Little Star

Exhibition at Small Gallery, Los Angeles, USA

Work: comma.data.space: 11 Ghz

Performance at the Moving Image Centre in Auckland, New Zealand

Work: comma.data.return :: 56:30 – 21:1

Performance at Version festival, Auckland, New Zealand

Work: listening_stations v0.3: langmuir waves

Exhibition at the Physics Room, Christchurch, New Zealand

Work: re:Play

Exhibition at Artspace in Auckland, New Zealand

Work: re:Play

Exhibition & education programme, South Africa

Work: re:Play

Exhibition at the Reg Vardy Gallery, Sunderland, UK

Work: Free Radio Linux, as part of the Art for Networks exhibition

Exhibition at Museum of European Photography/ Maison Europeenne de la Photographie, Paris, France

Work: listening_stations, as part of @rt Outsiders exhibition

Exhibition at the Physics Room, Christchurch, New Zealand

Work: data.spac.ereturn, as part of the Audible New Frontiers exhibition

Locative media Residency at K2, Karosta, Latvia

Work: Locative Media

Exhibition at Turnpike Galleries, Leigh, UK

Work: Free Radio Linux, as part of the Art for Networks exhibition

Exhibition at Fruitmarket Galleries, Edinburgh, UK

Work: Free Radio Linux, as part of the Art for Networks exhibition

Radio show on Resonance 104.4FM, London, UK

Work: r a d i o q u a l i a on resonanceFM

Exhibition at the Generali Foundation, Vienna, Austria

Work: listening_stations as part of the Geography and the Politics of Mobility exhibition

Exhibition at Chapter, Cardiff, UK

Work: Free Radio Linux, as part of the Art for Networks exhibition

Performance & Broadcast, Ars Electronica, Linz Austria

Work: Radiotopia @ Ars Electronica

Radio Broadcasts on Austrian National Radio, Vienna, Austria

Work: i s o l

Exhibition at CCCB, Barcelona, Spain

Work: frequency clock – gallery installation – [sNr v.0.1]

Sonar 2001, Barcelona, Spain

Action & Broadcast, Ars Electronica, Linz, Austria

Work: Take Over Cultural Channel

Performance, Residency & Symposium at, Ventspils International Radio Astronomy Centre, Latvia

Work: Acoustic Space-Lab

Exhibition at Video Positive, Liverpool, UK

Work: Frequency Clock – gallery installation – [ vp00 v.0.0.3 ]

Workshop & Performance, Adelaide Festival of the Arts, Adelaide, Australia

Work: Closing the Loop 2000

Seminar & Performance at Lux Centre, London, UK

Work: Tuning the Net

Performance at the Stockton Festival, Stockton, UK

Work: transitions & undercurrents part of live-stock

Exhibition & Performance at OK Centrum, Ars Electronica, Linz, Austria

Work: pso.Net, as part of Sound Drifting

Exhibition at Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide, Australia

Work: Frequency Clock – gallery installation – [ eaf v.0.0.2 ]

Exhibition at Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide, Australia

Work: Illata

Exhibition at Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

Work: e Q

Performance at LADA98 Festival, Rimini, Italy

Work: we are alive and well but terribly uncommunicative

Exhibition, Ars Electronica, Linz, Austria

Work: Frequency Clock – gallery installation – [ aec98 v.0.0.1 beta ]

Performance, Ars Electronica, Linz, Austria

Work: 56h LIVE!: Acoustic Space

Exhibition at Bregenz Festival, Bregenz, Austria

Work: gl^tch.bot

Performance and presentation at net.radio.days 98, Berlin, Germany

Work: self.e x t r a c t i n g.radio (.ser)

Online Project

Work: self.e x t r a c t i n g.radio (.ser)

Exhibition at the Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts, Tokyo, Japan

Work: The Qualia Dial

Exhibition at Fabrica New Media Art Institution, Italy

Work: Balance

more to do….

Streaming Suitcase

PliegOS

Re:mote

Low Res

Skint Stream

Open Source Streaming Alliance

Open Channels for Kosovo

self.extracting.radio

ovalmaschina

Gema

simpel