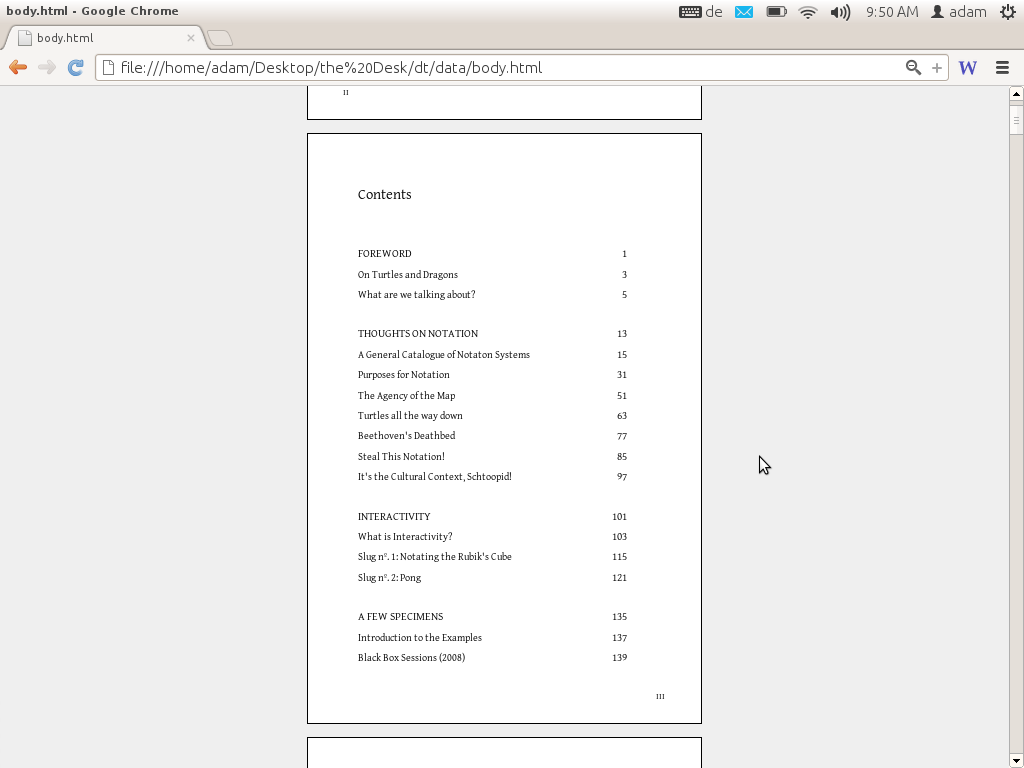

“Collaboration on a book is the ultimate unnatural act.”

—Tom Clancy

One of the most obvious opportunities open to online book production is collaboration. Of course, collaborative writing actually has a somewhat (unfairly) tainted name. During the first wave of wiki-mania, Penguin books conducted an experiment called A Million Penguins1, a collaborative writing project using a wiki. By all accounts, it was more successful as a social experiment than a literary experiment. I think most people think of this kind of thing when they think about collaborative writing. It's an interesting experiment, the thinking goes, but possibly it is not able to produce the same quality as a single-authored work.

However, let’s not forget that ALL books are produced collaboratively. Books generally carry the name of a single author but this is because the publishing industry trades on this. Publishing is a star system and its bottom line relies on it. It is better for a publisher to build up one star than distribute the glory over the 2,5, or 10 who were actually involved in producing the book. As a general rule acknowledging collaborative production is not good for business.

Rather than deny collaboration occurs, it is better to consider whether the character of the collaboration is weak or strong. Borrowing from a list of continuum sets outlined for collaboration in the book Collaborative Futures2 we could characterise it something like this:

- Weak – A single writer completes a work and secondary collaborators discuss or change elements with little or no interaction. For example, a friend reads and discusses elements or a proofreader is commissioned to clean the work up. In the case of the proofreader, little or no interaction occurs between the original creator and the proofreader although they are both aware of the proof reader’s role and changes in the text. The text is monolithic and attribution is solely to ‘the author’. An example would be any Tom Clancy work.

- Stronger – A single writer works with an editor, colleague, family member or friend to shape the text throughout the writing process. It is in part a form of mentor – writer relationship with the boundaries negotiated in a fluent and ongoing nature. The collaborator will make direct changes as challenges and suggestions. The text is monolithic but possibly with shared notes, and attribution is to ‘the author’ with thanks in an additional credit note to those that helped. This is a very typical methodology for publishers but also many works embrace this process informally. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is an example where many have argued that Mary Shelley formed a collaboration like this with her husband Percy Shelly.

- Strong – A multi-authored work where multiple collaborators share various levels of authority to act on the text in a highly modular and seemingly autonomous fashion. Although there is something of an over-reliance on the Wikipedia as an example, its unusually evolved structure makes it a salient case. Collaboration is remote but a coordinating and shared goal is clear: construction of an encyclopedia capable of superseding one of the classical reference books of history. The highly modular format affords endless scope for self-selected involvement on subjects of a user’s choice. Ease of amendment combined with preservation of previous versions (the key qualities of wikis in general) enable both highly granular levels of participation and an effective self-defense mechanism against destructive users who defect from the goal. Attribution is shared.

- Intense – A multi-authored work where the collaborators decide on the scope and character of the book in close and intense discourse throughout the production process. It is generally a very egalitarian environment and permission is not sought or needed to change a colleague’s work. FLOSS Manuals, originally established to produce documentation for free software projects, is a good example. Their method usually involves the assembly of a core group of collaborators who meet face- to-face for a number of days and produce a book during their time together. Composition generally takes place on an online collective writing platform, integrating wiki-like version history and a chat channel. In addition to those physically present, remote participation is solicited. It is necessary to come to an agreed basic understanding between collaborators through discussion of the scope and purpose of the book. Once underway both content and structure are continually edited, discussed and revised. The text is modular with granularity on the chapter level. Attribution is shared and often not as important as other forms of collaboration.

Producing books online obviously opens up some very interesting possibilities for collaboration. First, unlike a typical writer’s room, the net is a public space. That multiplies the possibility of making connections and working with people you may not know. It also means that you could box yourself in and open the door just to those you want to let in. The point is that you have the choice.

In addition to this continuum, there are open and closed collaborations. Open collaboration is an open door policy where anyone can come in and participate. A closed collaboration is where the boundaries of participation are set by social or technical means. Open and closed is a continuum characterised by the strong or weak porous nature of the boundaries. Closed collaboration is the default for the production of almost all books at the moment but some of the most amazing results can come from opening yourself up to open collaboration. My experiences working 5 years like this with a repository of 300 books and 4000 collaborators can recount many stories regarding this as the repository is completely open. Anyone can register and edit any book. As a result of these experiences, I find the case for ‘open collaboration’ extremely compelling. Interestingly, however, the more intensive the collaboration is the more difficult it is to sustain openness. New contributors may have missed formative discussions regarding the book and struggle to find a ‘way in’ to the content, additionally, new contributors may find it hard to enter the close-knit social fabric that is created as people work intensely together over time.

The following are two examples of collaborative workflows enabled by online book production. They investigate different points along the collaborative continuum. The first example is from James Simmons. James wrote several books online in a manner he calls a ‘Book Slog’ or ‘collaborating without co-authors’ – you might think of it as ‘the normal way’ to make books. The second example is of accelerated book production using a collaborative process known as a Book Sprint.

The normal way…

From the words of James Simmons:

A “Book Slog” is pretty much the normal way of writing a book. It is what most publishers would nail (attribute) to a single author. The long road to producing a book. For example: The book will, of necessity, take more than a week to write. More than likely it will take months, and will involve much research. The main author will end up knowing much more after finishing the book than he did when he began it. The book will have one main author, who will do most of the actual writing. The book may or may not have other contributors.The contributions of others may be informal. Other contributors will not be as highly motivated as the main author, or may have their own motivations that are not the same as the main author.The contributors will likely never meet face to face.

The question is, does online production have anything to offer the Slogger? Based on my own experiences, I would have to say it does. I used Booki (now Booktype) for my books. The main reason to use Booki rather than a word processor to write a book is to effectively collaborate with other authors. I have completed two books this way (and the Spanish translation of my first FLOSS Manual would definitely qualify as a third), so my opinions on this might be worth something.

Some might not think of these books as a collaborative effort, since I wrote every word, but in a very real sense they are collaborative works. I got lots of feedback from other developers, help in debugging my examples, help resolving problems with the test environments, and many useful suggestions. Writing the book on the web made that kind of collaboration much easier.

There were a couple of people who offered to write chapters, but this did not come to pass. In the end, this didn’t matter; the books ended up doing what they needed to do.

After the first book was published, there was interest in creating a Spanish version. Some of the most successful OLPC projects have been in South America, so I definitely wanted there to be a Spanish version. Unfortunately, I don’t speak any Spanish, so I didn’t feel qualified to do it. After the translation project got set up, a couple of people got accounts and looked over the book, and one of them translated a few paragraphs. Several of the people who had offered to help were concerned that they did not have the technical knowledge to translate the book, and for several days it looked like nobody was going to work on it.

A friend suggested using Google translate to create a base translation that native speakers could correct. I ended up using Babel Fish instead because the HTML generated by Google Translate had a lot of extra stuff in it like JavaScript and the original English text being translated. After I started doing this, a retired teacher who was fluent in Spanish started to correct the text, and I went through it and untranslated things that should not be translated, like code examples. It really needed native speakers to get it into shape. The retired teacher sent out an email on some lists explaining that we had a translation going that needed to be corrected. After that, several native speakers got accounts on the site and started to correct the text.

What I learned from this, is that starting a book from nothing is intimidating. However, once the book reaches a critical mass and there is no doubt that there will be a finished book, you’ll find that getting help and feedback is easier, almost inevitable.

The best motivation to collaborate on writing a book is a desire for the book to exist. To quote Antoine de Saint-Exupery:

“If you want to build a ship, don't drum up people together to collect wood and don't assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea”

If you can sell people on the idea of the book, you’ll get collaborators. That’s another reason you may have to write a substantial chunk of the book before collaborators show up. A partial book is easier to sell than an idea for a book.

With the book “E-book Enlightenment,” I collaborated with some people from an organization in Oregon called the Rural Design Collective. This is a group that has done work for both the Internet Archive and the One Laptop Per Child project. They have a summer mentoring program where talented students get involved with an Internet project and learn skills that may lead to a future career.

When I announced that Make Your Own Sugar Activities! was finished, I got an email from Rebecca Malamud of the RDC congratulating me. I told her about my plans for a new book and asked if she’d like to contribute.

At that point, the RDC was contemplating what to do for their summer mentoring program and they decided that working on my book might be just what they were looking for.

We all wanted the book to exist, but for different reasons. The RDC is focused on training young people to create websites, and so they chose to focus on the graphic design of the book more than the content.

The RDC found a talented young artist who did some terrific cover and interior illustrations (the small ones at the top of each chapter). The cover illustration that everyone liked didn’t really go with the title I had proposed, so I ended up changing the title. (The same artist also did new cover art for the printed Make Your Own Sugar Activities!) Another of their mentees created stylesheets which they used to create a really beautiful bound and printed edition of the book.

In addition to the RDC’s work, I also got much help and encouragement from the forums of DIY Book Scanning and Distributed Proofreaders. Again, this is not collaboration in the way the word is normally used, but it was a vital contribution to the book. I would post a link to the book on the FLOSS Manuals website and ask for comments. The comments I got often contained valuable information and suggestions.

So, in summary, I’d say that online production is a good way to collaborate on writing a book!

Book Sprints

A more radical action for online book production is the Book Sprint3.

A Book Sprint is a facilitated process that brings together a group of people to produce a book in 3-5 days (although it has been done in shorter time). While the group meet in person, the books are produced collaboratively using networked (online) end-to-end book production tools. Often remote participants also join in. Usually, there is no pre-production and the group is guided by a facilitator from zero to published book. The books produced are high-quality content and are made available immediately at the end of the sprint in printed (using print-on-demand services) and e-book formats. Book Sprints produce great books and they are a great community and team building process.

The quality of these books is exceptional, for example, Free Software Foundation Board Member Benjamin Mako Hill said of the 280 page Introduction to the Command Line manual produced in a two-day Book Sprint:

“I have written basic introductions to the command line in three different technical books on GNU/Linux and read dozens of others. FLOSS Manual’s Introduction to the Command Line is at least as clear, complete, and accurate as any I’ve read or written. But while there are countless correct reference works on the subject, FLOSS’s book speaks to an audience of absolute beginners more effectively, and is ultimately more useful, than any other I have seen.”

Book Sprints offer an exciting and fun process to work with others to make that book you always felt the world needed. It is a fast process – zero to book in 5 days. Seem impossible? It’s not, its very possible, fun, and extremely rewarding in terms of output (a book!) and the team building that occurs during the process.

There are three common reasons to do Book Sprints:

- Producing a book that will be ready at the end of the Sprint drives the process and helps to justify the effort.

- Producing knowledge in a short period of time forces the participants to master the issues related to their subject. They will work intensely on content together, share and reshape their understanding of a collective question.

- Reinforcing or creating social links. Mobilizing a community to produce a book or text forges and solidifies a sense of belonging among participants.

As a result, I have experimented a lot with this format. To understand the many facets of collaboration in this process let’s look at the second case study – Collaborative Futures.

This book was first written over 5 days (Jan 18-22, 2010) during a Book Sprint in Berlin. 7 people (5 writers, 1 programmer and 1 facilitator) gathered to collaborate and produce a book in 5 days with no prior preparation and with the only guiding light being the title ‘Collaborative Futures’. These collaborators were: Mushon Zer-Aviv, Michael Mandiberg, Mike Linksvayer, Marta Peirano, Alan Toner, Aleksandar Erkalovic (programmer) and Adam Hyde (facilitator).

The event was part of the 2010 Transmediale Festival . 200 copies were printed the same week through a local print on demand service and distributed at the festival in Berlin. 100 copies were printed in New York later that month.

The book was revised, partially rewritten, and added to over three days in June 2010 during a second book sprint in New York, NY, at the Eyebeam Center for Art & Technology as part of the show Re:Group Beyond Models of Consensus and presented in conjunction with Not An Alternative and Upgrade NYC.

Collaborative Futures – Second Edition cover by Galia Offri

Day one of the first sprint consisted of presentations and discussions.

During this first day we relied heavily on traditional ‘unconference’ technologies—namely colored sticky notes. With reference to unconferences we always need to tip the hat to Allen Gunn and Aspiration for their inspirational execution of this format. We took many ideas from Aspiration’s Unconferences during the process of this sprint and we also brought much of what had been learned from previous Book Sprints to the table.

First, before the introductions, we each wrote as many notes as we could about what we thought this book was going to be about. The list consists of the following:

- When Collaboration Breaks.

- Collaboration (super) Models.

- Plausible near- and long-term development of collaboration tech, methods, etc. Social impact of the same. How social impact can be made positive. Dangers to look out for.

- Licenses cannot go two ways.

- Incriminating Collaborations.

- In the future, much of what is valuable will be made by communities. What type of thing will they be? What rules will they have for participation? What can the social political consequences be?

- Sharing vs Collaboration.

- How to reconstruct and reassemble publishing?

- Collaboration and its relationship to FLOSS and GIT communities.

- What is collaboration? How does it differ from cooperation?

- What is the role of ego in collaboration?

- Attribution can kill collaboration as attribution = ownership.

- Sublimation of authorship and ego.

- Models of collaboration. Historical framework of collaboration. Influence of technology enabling collaboration.

- Successful free culture economic models.

Then each participant presented who they were and their ideas and projects as they are related to free culture, free software, and collaboration. The process was open to discussion and everyone was encouraged to write as many points, questions, statements, on sticky notes and put them on the wall. During this first day we wrote about 100 sticky notes with short statements like:

- “Art vs Collaboration”

- “Free Culture does not require maintenance”

- “Transparent premises”

- “Autonomy: better term than free/open?”

- “Centralized silos vs community”

- “Free Culture posturing”

…and other cryptic references to the thoughts of the day. We stuck these notes on a wall and after all of the presentations (and dinner) we grouped them under titles that seemed to act as appropriate meta tags. We then drew from these groups the 6 major themes. We finished at midnight.

Day two—10.00 kick off and we simply each chose a sticky note from one of the major themes and started writing. It was important for us to just ‘get in the flow’ and hence we wrote for the rest of the day until dinner. Then we went to the Turkish markets for burek, coffee and fresh pomegranates.

The rest of the evening we re-aligned the index, smoothed it out, and identified a more linear structure. We finished up at about 23.00.

Day three—At 10.00 we started with a brief recap of the new index structure and then we also welcomed two new collaborators in the real-space: Mirko Lindner and Michelle Thorne. Later in the day, when Booki had been debugged a lot by Aco, we welcomed our first remote collaborator, Sophie Kampfrath. Then we wrote, and wrote a bit more. At the end of the day we restructured the first two sections, did a word count (17,000 words) and made sushi.

After sushi, we argued about attribution and almost finished the first two sections. Closing time around midnight.

Day four—A late start (11.00) and we are also joined by Ela Kagel, one of the curators from Transmediale. Ela presented about herself and Transmediale and then we discussed possible ways Ela could contribute and we also discussed the larger structure of the book. Later Sophie joined us in real space to help edit and also Jon Cohrs came at dinner time to see how he could contribute. Word count at sleep time (22.00): 27,000.

Day five—The last day. We arrived at 10.00 and discussed the structure. Andrea Goetzke and Jon Cohrs joined us. We identified areas to be addressed, slightly altered the order of chapters, addressed the (now non-existent) processes section, and forged ahead. We finished at 2200 on the button. Objavi, the publishing engine for Booktype, generated a book-formatted PDF in 2 minutes. Done. Word count ~33,000.

Some months later the book was ‘re-sprinted’ in New York with another group of people. The following contains excerpts from the experiences and voices of those involved:

Over the course of the second Book Sprint, we often paused to reflect on the fact that editing and altering an existing book (one originally written five months prior by a mostly different group of people) is a completely different challenge than the one tackled by the original sprinters. While the first author group began with nothing but two words -Collaborative Futures- words that could not be changed but were chosen to inspire. This second time we started with 33,000 words that we needed to read, understand, interpret, position ourselves in relationship to, edit, transform, replace, expand upon, and refine.

Coming to a book that was already written, the second group’s ability to intervene in the text was clearly constrained. The book had a logic of its own, one relatively foreign to the new authors. We grappled with it, argued with it, chipped at it, and then began to add bits of ourselves. On the first day, the new authors spent hours conversing with some of the original team. This continued on the second day, with collaborators challenging the original text and arguing with the new contributions

If this book is a conversation, then reading it could be described as entering a particular state of this exchange of thoughts and ideas. Audience might be a word, a possibility and potential to describe this readership; an audience as in a performance setting where the script is rather loose and does not aim for a clear and definite ending. (It is open-ended by nature); an audience that shares a certain moment in the process from a variable distance. The actual book certainly indicates a precise moment, thereby it IS also a document, manifesting some kind of history in/of open source and counter-movements, media environments, active sites, less active sites, interpassivity (Robert Pfaller), residues of thought, semi-public space; history of knowledge assemblages (writers talked about an endless stitching over…) and formations of conversations.

The book as it is processed in a Sprint, is a statement about and of time. The reader or audience will probably encounter the book not as a “speedy material”. Imaginary Readers, Imaginary Audience. We came to recognize, however, that the point was not to change the book so that it reflected our personal perspectives (whoever we are), but to collaborate with people who each have their own site of practice, ideology, speech, tools, agency. In service of a larger aim, none of us deleted the original text and replaced it to reflect our distinct point of view. Instead, we came to conceive of Collaborative Futures as a conversation. Since the text is designed to be malleable and modifiable, it aims to be an ongoing one. That said, at some point this iteration of the conversation has to stop if a book is to be generated and printed. A book can contain a documented conversation, but can it be a dynamic conversation? Or does the form we have chosen demand it become static and monolithic?

In the end, despite our differences, we agreed to contribute to the common cause, to become part of the multi-headed author. Whether that is a challenge to the book or a surrendering to it, remains unclear.

- http://thepenguinblog.typepad.com/the_penguin_blog/2007/03/a_million_pengu.html^

- http://www.booki.cc/collaborativefutures/continuum/^

- http://www.booksprints.net^