Awesome startup founded by my buddy Nellie. Uses paged.js in the core and Nellie has been an active contributor. Whoot!

Donate here! https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/nelliemckesson/cartoonists-classics-a-high-tech-book-publishing-e

Awesome startup founded by my buddy Nellie. Uses paged.js in the core and Nellie has been an active contributor. Whoot!

Donate here! https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/nelliemckesson/cartoonists-classics-a-high-tech-book-publishing-e

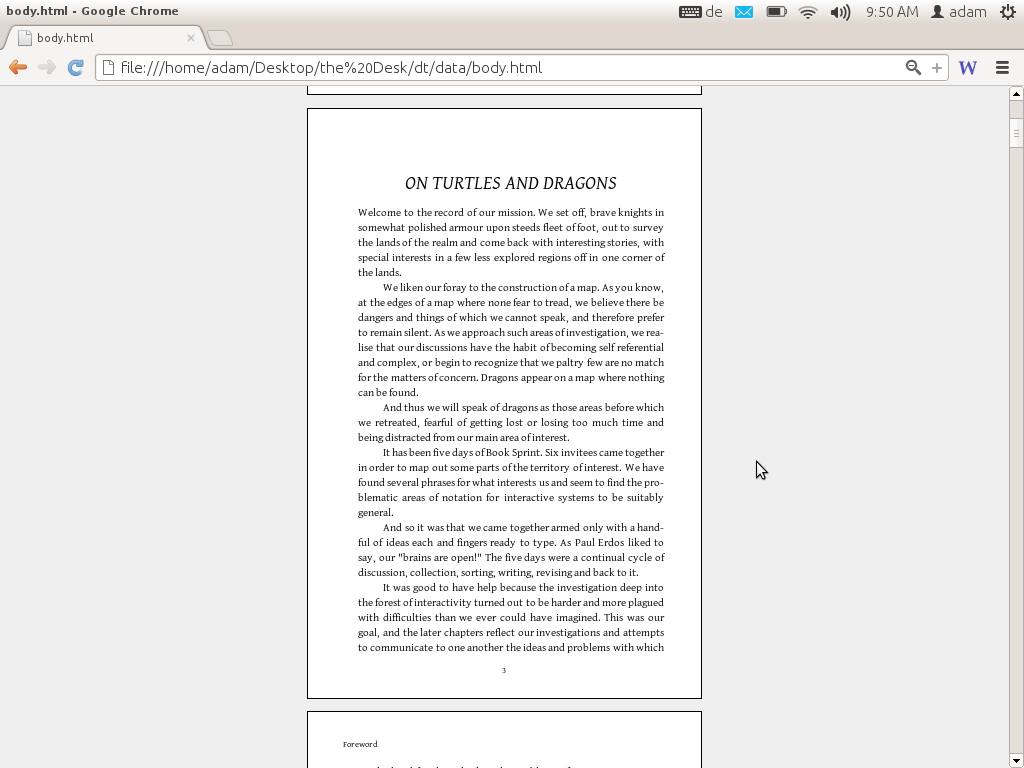

It brings us closer to in-browser print design and a step closer to the demise of desktop publishing. Although book.js is in an alpha form, it is a clear demonstration that the browser is fast becoming the new environment for print design.

That is an enormous leap, one that not only means print design environments can be developed using browser-based technology, which will surely lead to enormous innovation, but it radically changes the process of design. The design of books and paper products enters a networked environment. This will enable more possibilities for collaborative design and bring print production into the workflow of online content production. There will be no need to exit browser-based environments to take content from source to final output. This means there is no need to juggle multiple sources for different stages of production, there can be efficiency gains through integrated workflow, and, most interestingly, content production and design can occur simultaneously…

It is also important to realise that these same technologies, book.js and others that will follow it, can make the same things possible for ebook production. Flowing text into PDF for a paper book, or into e-reader screen display dimensions, is the same thing. This enables synchronous in-browser design and production on a single source for multiple output formats.

book.js is Open Source, developed originally by and for Booktype, but the team is looking to collaborate with whoever would like to push this code base further. It is at the alpha stage and a lot of work still needs to be done, so please consider jumping in, improving the code and contributing back into the public repository.

book.js demo and information can be found here . Note: This is strictly for the geeks to try as it requires the latest version of Chrome; see the demo information.

Originally posted on O’Reilly, 29 October 2012

http://toc.oreilly.com/2012/10/bookjs-turns-your-browser-into-a-print-typesetting-engine.html

The vast majority of authors under the current dominant model of publishing don’t make any money. Authors do it for the chance to make money, and they do it for the advancement of their careers and their profile. There is no monster financial industry pouring money into culture and knowledge workers, instead they are pouring money into book production and distribution.

I mention this because one argument against free content is that people won’t get paid. However, people often don’t get paid for writing books anyway, so with free content, nothing has changed. Nevertheless, there are many profitable businesses that have for a very long time made a lot of money from the resale of free (in this case, out-of-copyright) material. Take Penguin Books, for example. They can’t stop competition with sales of out-of-copyright classics but seem to be doing all right nevertheless. You can get many of the same out-of-copyright books at Project Gutenberg for free, but that doesn’t stop Penguin Books and many other publishers selling the same material in both paper and digital form and making a good profit. In addition, I believe that free books have revenue models which are more open to content producers than are the existing publishing models.

There are some major changes in the industry that point to this. First, it is reported that ebook sales are going through the roof. Amazon has reported that ebooks are the most popular book format1. Ebooks have lower costs for production, in fact, you can more or less say that producing an EPUB (a very popular and open ‘almost standard’ for ebooks) costs nothing. Find the right software and it’s done in minutes. This puts very profitable publishing in the path of federated publishing.

Second, business models are changing. The biggest shift I see is to put the money at the front of the production cycle instead of at the end. There are platforms like Unbound (http://www.unbound.co.uk/) that are giving this a go, and many successful examples in Kickstarter, such as Robin Writes a Book2 – a book project that raised $14,000 (USD) from crowdfunding. Robin Writes a Book by Robin Sloan is a fictional work funded before it was produced. In a blog post3 on Creative Commons the author states:

"I think the most important thing about a book is not actually the book. Instead, it’s the people who have assembled around it. It’s everyone who’s ever read it, and everyone who’s ever re- or misappropriated it. It’s everyone who’s ever pressed it into someone else’s hands [...] it’s that group of people that makes a book viable, both commercially and culturally. And without them — all alone, with only the author behind it — a book is D.O.A."

That’s a pretty good argument, from the inside of fringe cultural production, that it doesn’t need the current publishing industry to thrive. It also illustrates that social context is important for generating revenue. Sloan goes on to explain secondary economies he is trying to generate from the book.

There are many other examples of very well-funded books ($85,000 USD being the top earner4 for a book project on Kickstarter) that demonstrate a model we can all participate in as cultural and knowledge producers.

Kickstarter approaches have their issues, but they raise an interesting point – people are prepared to fund a book that they want before it is produced. That’s quite a reversal – the consumer is actively switching sides to become ‘part’ of the production team by helping finance the product. The advantage of this process is that if you can raise the funds for the project like this then you don’t have to rely on sales to recover your costs or make a profit. That means there is a better chance for the product to be a ‘no strings attached’ free product. The content can actually be free because no one is anxious to recover their costs from sales. That also means that the post-production phase can focus on distributing the content as far and wide as possible because at that stage the return is recognition through distribution. This can, if done well, help with the next project that needs funding… the better you are known for producing good quality free products, the easier it will be to convince people to help pay for their production. So getting the money before making the book is not only good sense, it is consistent with free culture values.

It is possible to consider at least two other ‘crowdfunding’ business opportunities for books – running a crowdfunding service as some kind of ‘Kickstarter for books’, and getting funding from crowds for your books. Clever publishing entrepreneurs might do both.

Kickstarter.com has taken up this concept of crowdfunding with what seems to be significant initial success. The premise is simple: an individual defines a project that needs funding, defines rewards for different levels of contribution, and sets a funding goal. If that pledges meet the funding goal, the money is collected from pledgers, distributed to the project creator, who uses the funding to make the project. If the project does not reach the funding goal by the deadline, no money is transferred. Most projects aim for between $2,000 and $10,000.

Kickstarter pledges are not donations, as most of the contributions are associated with tangible rewards, nor are they a form of micro-venture capital, as funders retain no equity in the funded project. While crowdfunding need not be limited in topic, Kickstarter is focused almost exclusively on funding creative and community-focused projects. Part of their goal is to create a lively community of makers who support each other. At the end of their first year, Kickstarter gave out a number of awards, including one to the project with the most contributors, the project that raised the most money, and the project that reached their goal the fastest. The award that might be most telling is for the “Most Prolific Backer”:

“Jonas Landin, Kickstarter’s Most Prolific Backer, has pledged to an amazing 56 projects. What motivates him? “It feels really nice to be able to partially fund someone who has an idea they want to realize.” blog.kickstarter.com/post/318287579/the-kickstarter-awards-by-the-numbers

This model is catching on and we can expect more nuanced and sector-driven approaches to financing book production this way. One such possibility, is finding organisations to sponsor book production and making the argument in business terms.

A while ago I worked with a Dutch organisation by the name of Greenhost.nl. They are a small hosting provider based in Amsterdam with a staff list of about 8. The boss wanted to bring the Greenhost crew to Berlin to make a book on Basic Internet Security and he wanted me to facilitate a Book Sprint to produce it. So we organised a Book Sprint, invited some locals to come and help, and sprinted the book over four days. In total, around 6 people were in attendance (including myself as facilitator) and we started on Thursday and finished the following Sunday, one day earlier than expected. The book is a great guide to the topic and quite comprehensive – 45,000 words or so in 4 days with lots of nice illustrations.

The following morning, the book went to the printers and then was presented in print form, 2 days later, at the International Press Freedom Day in Amsterdam.

The presentation at International Press Freedom Day was complimented by a PR campaign driven by Greenhost. The attention worked very well as the online version of the book received thousands of visits within a few hours (slowing our server down considerably at one point) and there was also a lot of very nice international and national (Dutch) press attention. This worked very well for Greenhost as this is the kind of promotional coverage that is otherwise very hard to generate. That makes sponsoring a Book Sprint a very good marketing opportunity for organisations.

There are some organisations that have taken this principle into their business. The President5 is a South Africa (Capetown)-based organisation that has won a lot of awards for their designs. They place great emphasis on book/content design as a more engaging and potent form of marketing for their clients.

There are of course some issues raised here the first being that this will only work for the sponsor if they keep their marketing-speak out of the book itself. If they put marketing texts into the book they sponsor, they are making marketing brochures, not books and they stand to look very bad. Let the book do what it has to do and get the kudos by saying you made it happen.

This kind of press is not only good for the organisations involved and good for the reader but it is good for the book itself because it raises the profile of the book, putting it in front of people that need it and can help improve it. This can, for example, raise the probability that a book will be voluntarily translated. A high-profile book can be an attractive prospect to voluntary translators. Not many people want to spend the hours translating a book that won’t be read, but if it’s a book with an established high profile then it’s a better proposition. To demonstrate this by example, Basic Internet Security (the book made by Greenhost) immediately had two groups start the German and Farsi translations voluntarily.

In addition to this, we also had unforeseen re-distribution channels open up for the book. In the case of this book, someone had gone to the trouble of creating a torrent (a peer-to-peer sharing method) and listed it on Pirate Bay. We didn’t create this torrent – someone noticed the book, downloaded it, and made the torrent themselves. It’s legal sharing and it works in favour of the book and the book’s producers.

Think about what kind of book your organisation may want to bring into the world. Think of a great book that would help make the world a better place. For example, are you a design or typography company? Want to make a book about How to Make Fonts? Are you a law firm? Want to make a book about basic rights in your country? Then design a PR strategy around the book that will justify the expense of its production.

Of course, this approach does not come without its issues. If people pay money to have something produced, then they generally do not like it if the thing produced disagrees or takes issue with them. Worse is the mindset that this can produce in the producers. Anticipating and avoiding disagreement is in effect a kind of self-policing that can stifle creativity especially when you are working collaboratively. Get a good facilitator!

Most of us know an ebook is a digital file that can be read by devices such as iPads and Kindles. There are many different kinds of ebook formats and each has its own strengths and weaknesses. Some ebooks made to be viewed on the Kindle, others on the iPad, still others for reading online via a web browser. Kindle, for example, works with the MOBI format, whereas the iPad-iBook reader works only with iBook or EPUB formats. EPUB is one of the most popular formats because no one owns the format as compared to, for example, the way Microsoft owns the .doc format. Anyone can produce an EPUB without having to pay royalties. That makes EPUB a popular type of ebook format for publishers.

What is important here, is that many of these ebook formats share a lot in common with the web page. EPUB, for example, in the words of the International Digital Publishing Forum (the group taking responsibility for managing the development of the format), is:

“…a means of representing […] Web content — including XHTML, CSS, SVG, images, and other resources — for distribution in a single-file format.”

EPUB pages are made of HTML, the language of the web. EPUB pages are web pages.

The change of carrier medium for books, from paper to HTML, changes everything. Publishers appear to believe that just the format of the book (from paper to electronic) and the distribution process (from bricks and mortar to net) have changed. These are enormous changes indeed, but what about everything else? What about the rest of the book’s life?

To get an understanding of how this transformation of the content medium from paper to web page affects things, let’s first take a bird’s eye view of the current life cycle of a book. Painting it with broad strokes, the book life cycle (still) looks something like this:

Digital networks and digital books, of course, have changed how publishers work. The disruption, however, has really been limited to the steps of object production and marketing strategies. Many publishers of genres from fiction to scientific journals do not have a workflow for the production of electronic books, they simply send their MS Word files to an outsourced business for transformation to EPUB. In their world, paper books are easier to produce than digital books. Even so, much has changed and can be captured in brief by the following:

Arguably, the life of a book has been reduced, as many book formats cannot be transferred from one device to another and so have only limited visibility. Books, for example, produced in Apple’s iBook Author do not follow the standard way of making EPUB and are often unreadable on non-Apple devices. This is changing a little with developments such as the Kindle app which can be installed on iPads and computers for reading books purchased on Amazon. However, there are still many issues.

What is most astonishing to me, is that there has been little or no innovation regarding the production of books. Sure paper and pen were replaced by typewriter and then a computer and word processing software. But these technologies largely support the same methods for making books. In 2013, many years into the digital media and digital network world, there is little change. We are still producing books as we did back in the days of handwritten manuscripts, except these days we can email the file to someone to check. It is as if the digital network is just a faster postal service.

There are some notable exceptions. For example, OReilly is experimenting with some networked and ‘agile’ (fast-moving and iterative) production processes, but overall, the innovation and change happening now within the publishing industry is constrained to everything that happens after the text is produced and before the book is archived by the reader.

As it happens, this is about as far as the publishing industry can innovate. They are too heavily invested in production workflows, tools and methodologies to change the production process. In addition, it is too difficult for publishers to consider changing as there is the fear such disruption could break things on a much deeper level. Single author works, for example, are an important part of reputation-based sales and you can’t change one without the other.

In many ways, it is simply bad business and logistically too hard for publishers to innovate around production as it cannibalises their existing models. At the other end of the cycle, publishers do not seem to be interested in the life of the book beyond purchase, except where they retard life expectancy with DRM, delete the book file or link from your device, or surveil your reading habits in order to offer the next book for your consumption. After reading the book on your reader, it sits there as it would on a bookshelf.

Ironically for the publishing industry, the biggest opportunities are in the areas they are not addressing. The new publishing world, which might be populated largely by those individuals, collectives, ‘groupings’ and organisations that are currently not publishers, looks like this:

The beginning of this cycle and the end are intimately linked. The conditions for collaboration have a lot in common with the conditions for extending the life of books.

The life cycle of a book is changing because books are web pages and production is coming online. Collaborative production is one very rich opportunity and it looks very unlike linear production models. In intensive collaborative or open collaborative environments, roles are concurrent and fluid. It is possible for one person to write original material, borrow material, improve another’s material, then proofread others’ work, edit and comment on design. This is all possible because the production environment is the browser. At its most intense, collaborative browser-based production becomes transparent. Anyone can look at the evolution of the book and witness the changes as they occur. In this kind of process, discourse becomes necessary and collaborators open up rich and valuable discussions which become part of the book. The book becomes a product of collective discourse and the discourse is often as rewarding as the book that comes from the process.

These conditions often lead to the book having an extended life as communities of collaborators form around the book and carry the book forward, amending and improving the work. The life of the work is then connected to the health of the connected networked community.

As the new production and carrier medium for books, HTML transforms everything. It leads naturally to collaborative production and the extended life of content. However, most of these transformations are occurring outside the existing publishing industry, leaving the future of publishing in your hands.

See also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Edl_HvcEjs

[Produced sometime in 2011]