So, I have a pet thesis…. it goes something like this… Open Source, as we know it out there in the wild, is a code-centric pursuit. Its roots are in code, the culture is all about developers solving problems, the tooling is code-centric, and the culture values code above all else. That is not a very controversial thesis so far. However, I have experienced a lot of kickback when I get to the next bit… and that is, open source has both succeeded and failed because of the these characteristics. It has succeeded to produce a lot of code, and a lot of tools and libraries that developers need, but it has failed in any category of software where the primary beneficiaries of the software are not developers.

To me it makes sense. But bringing it up has produced so much blowback, notably from long-time open source practitioners, that it only reinforces to me the truth in the mini thesis. There is a huge blind spot in open source culture that does not recognise where it has failed. It is a pity because I believe the first step in succeeding in these areas is to recognise why open source has failed. Only then can you fix it.

I believe it will take a long time to change this and I once had aspirations to be part of the fix-it movement, but I think it’s too long a game so I have elected instead to play a part in addressing these issues in realms where I know I can have an immediate effect. Hence, in Coko, a not for profit I co-founded, we are spending a lot of time to see how we can create an open source project that values all contributions as much as traditional open source values code contributions.

Part of this is making way for UX design. It is pretty much the high-value role, when it comes to conquering the most obvious limitations in open source, since it is where the rubber hits the road when it comes to ‘user’ meets software.

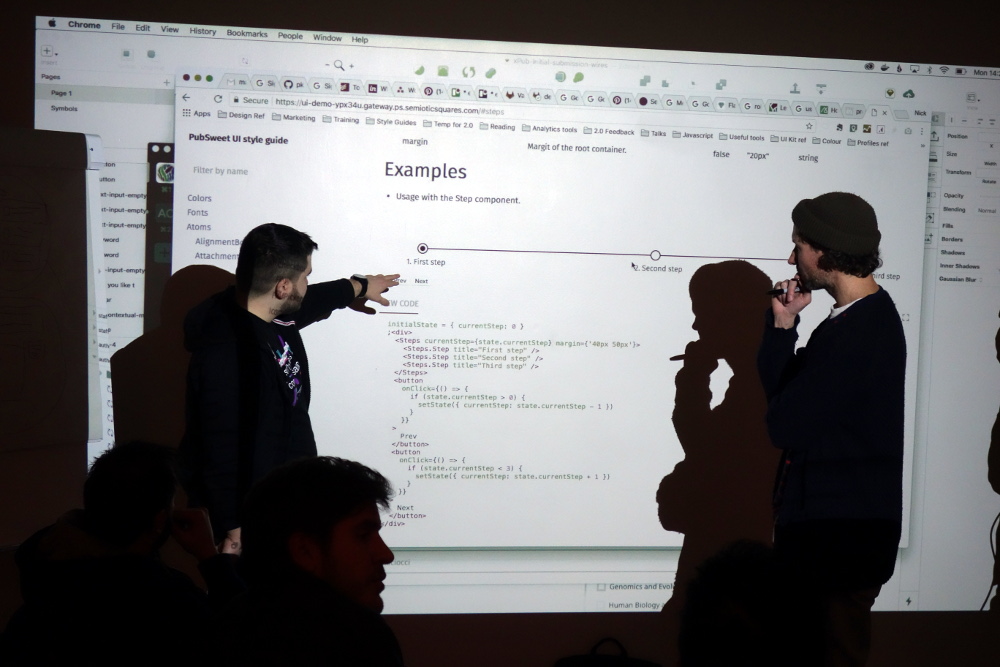

In the Coko community, Julian Taquet and Nick Duffield (eLife) are putting a lot of time into this with the able assistance of Yannis Barlas (there has also been a lot of excellent input from Sam and Tam from YLD and others). I’ve shepherded the process from a distance – setting the scene and making the space for the right people to do the right work and making sure this work has the right value accorded to it in the Coko culture.

So, in essence, we have realised that collaboration in UX comes down to three things:

- identifying the common ground

- tooling

- process

Common Ground

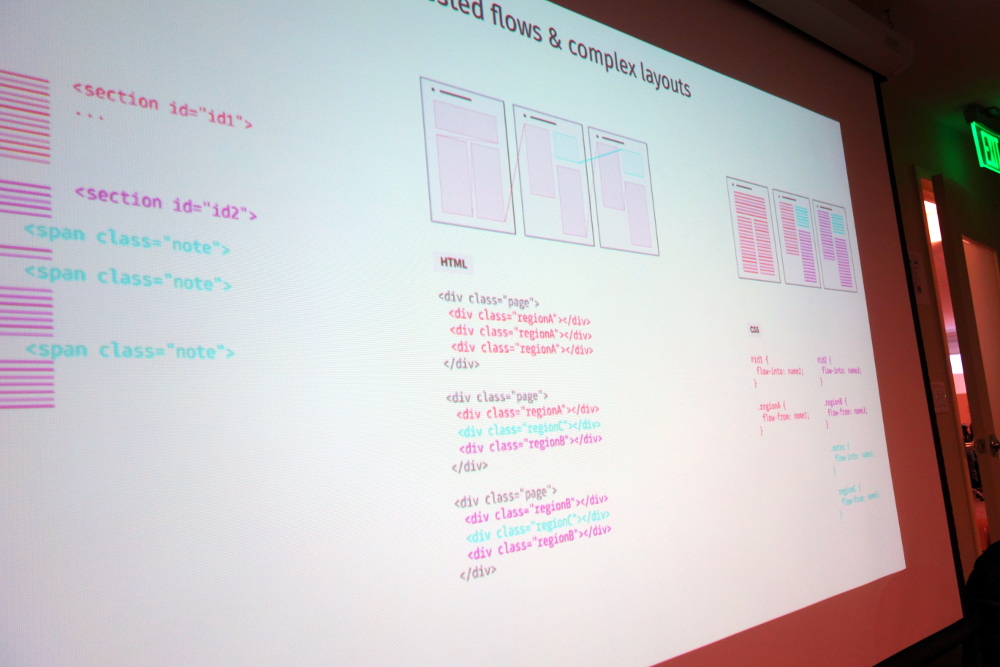

Identifying the common ground actually took some discussion. We initially thought the common ground – think of it as UX space shared across projects – was on the page-level. We thought, for example, one org would need a dashboard and so they make it and others can use it. While this is true for a limited number of specific page level components it soon became obvious that there was a higher opportunity for reuse should we break the page-level components down into smaller components. We then had a short period of lexicon confusions (“duh. what sort of component is a login?”) until we settled on Brad Frost’s atoms and molecules concepts and lexicon.

After that, we could make faster progress as we had identified, and could talk about, a new level of component that had infinitely more opportunities for reuse across projects.

That was the highest level common ground we identified.

Tools

Next, we moved onto tooling… there had been a lot of discussion about this. The trick was to get the designers to experiment with and understand the options. It also highlighted the fact that in each collaborating org there was a different workflow that might play into some discussions and not into others. For example, Julian from Coko does as much of the tweaking of CSS variables and values in the code, whereas Nick from eLife does the design and then hands these designs to others to implement. So, in many ways, the questions about tooling are informed by these workflows ;and different people, even if identified as having the same kind of role, have very different questions and needs. This is important to take into account and we will need to keep this very much in focus as we go forward. One easy way to keep issues of this in focus is to always insist that any discussion, workflow change or feature that affects design workflow must include the designers in that conversation. You get better results and people are much happier! Not to mention that it saves a lot of time as there is more informed discussion as you progress and fewer possibilities for major rollbacks because someone wasn’t looped in.

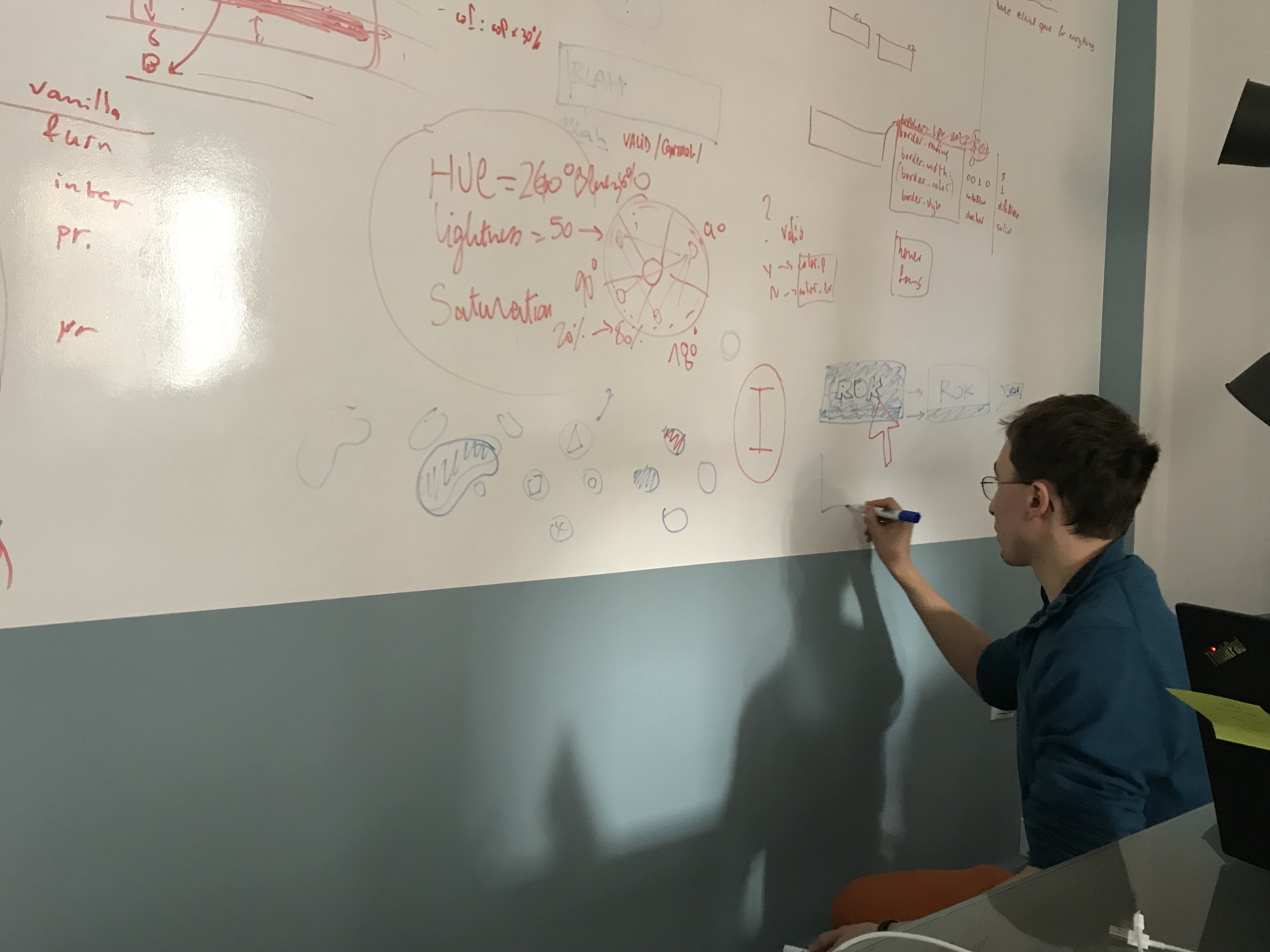

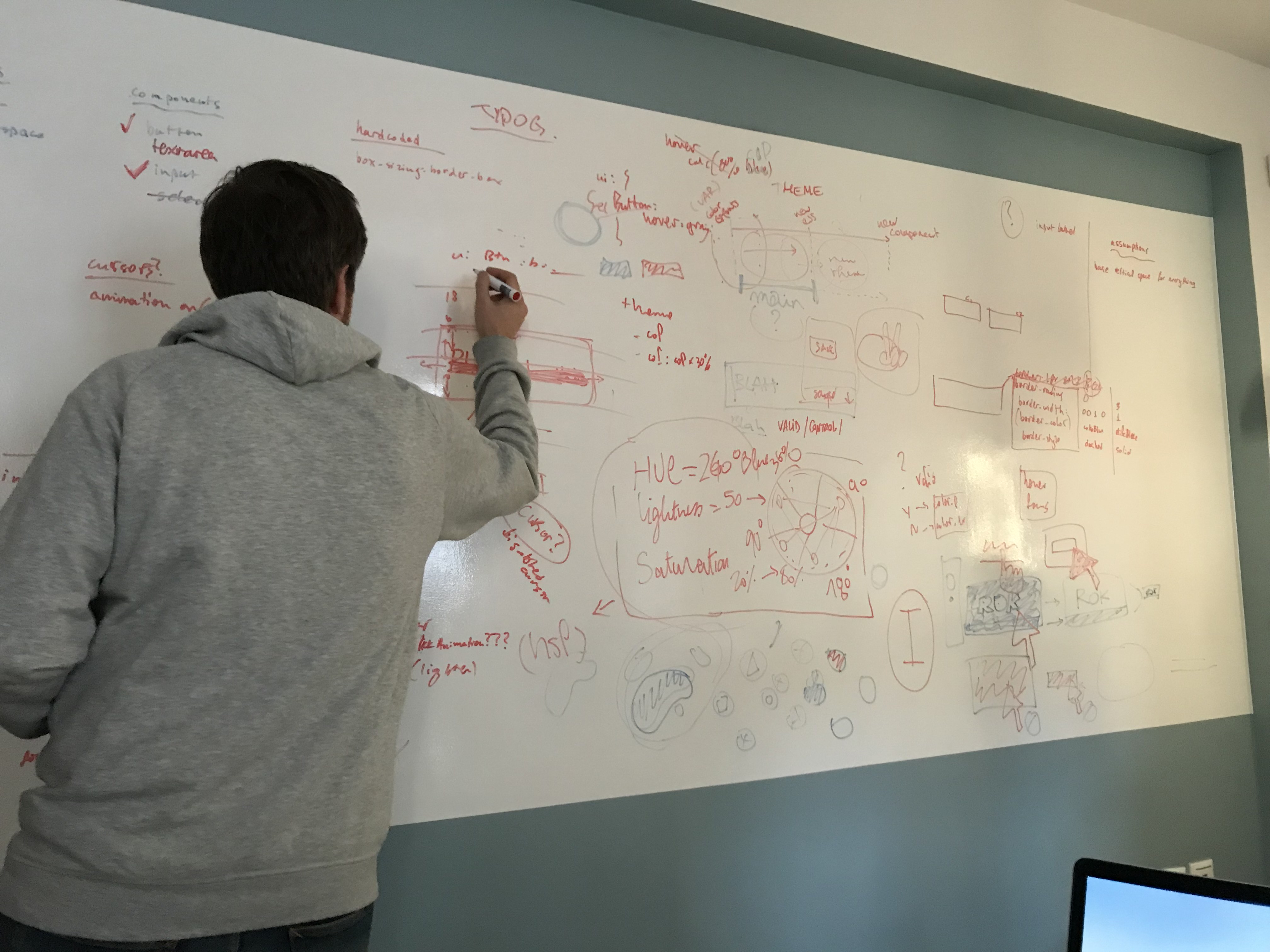

This conversation on tooling took quite a few weeks; there were many options on the table and we wanted to make sure the right people were in the right conversations. It came to a close, for at least the foundational stage, when Nick and Julien met with Yannis in Athens for a 3 day UX meet and nailed down the final agreements on tooling (amongst other things). This highlights to me also the need for periodic in person meets if you can manage it, as required. You can clear out a lot of ‘hanging issues’ in one swoop if you meet in person for short focused bursts.

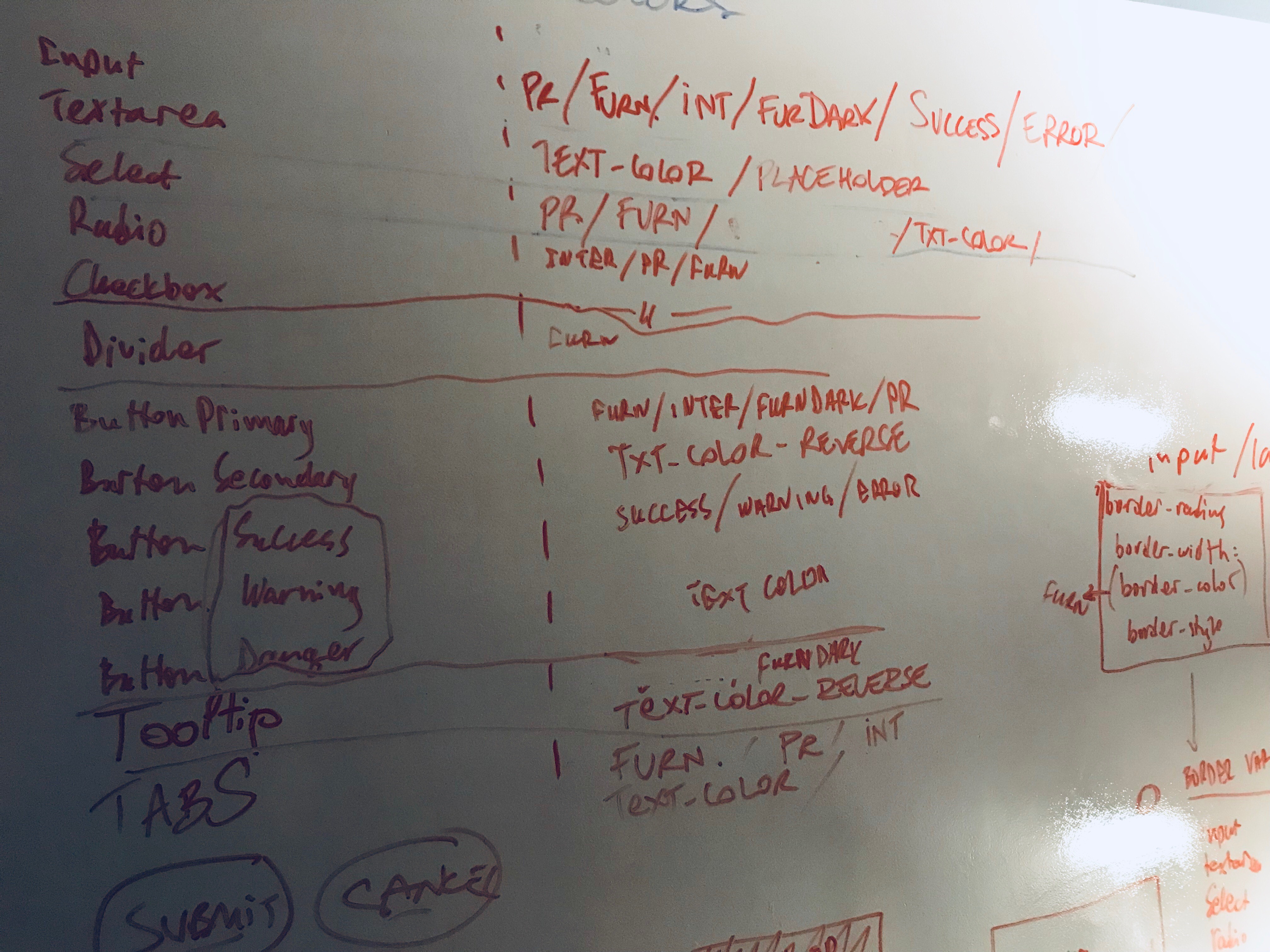

Below are some pics from this very important meet in Athens showing Nick, Julien, and Yannis at work on the whiteboard in our Athens office.

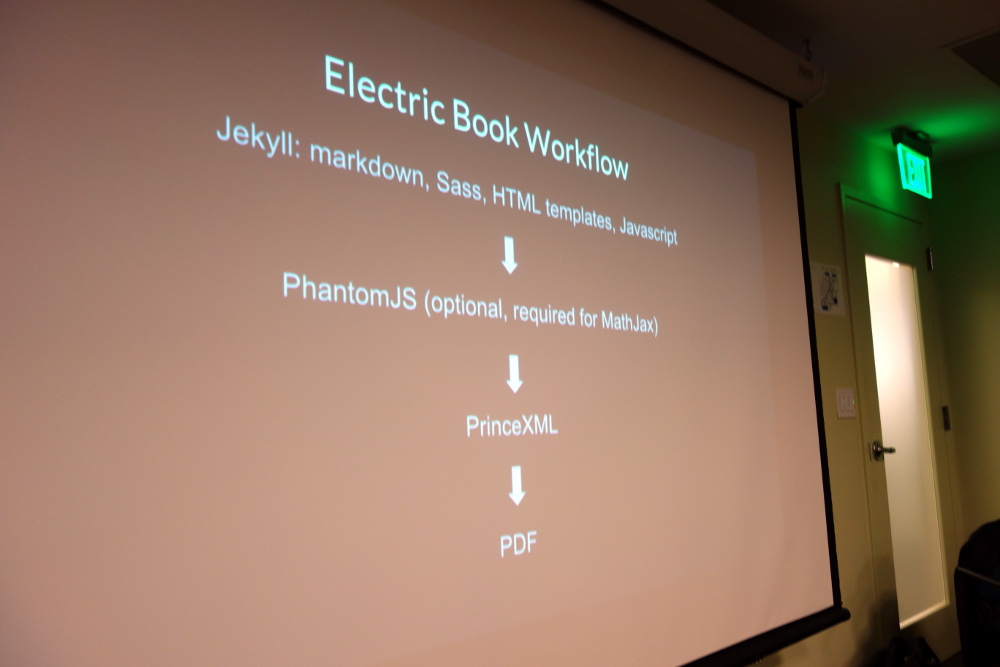

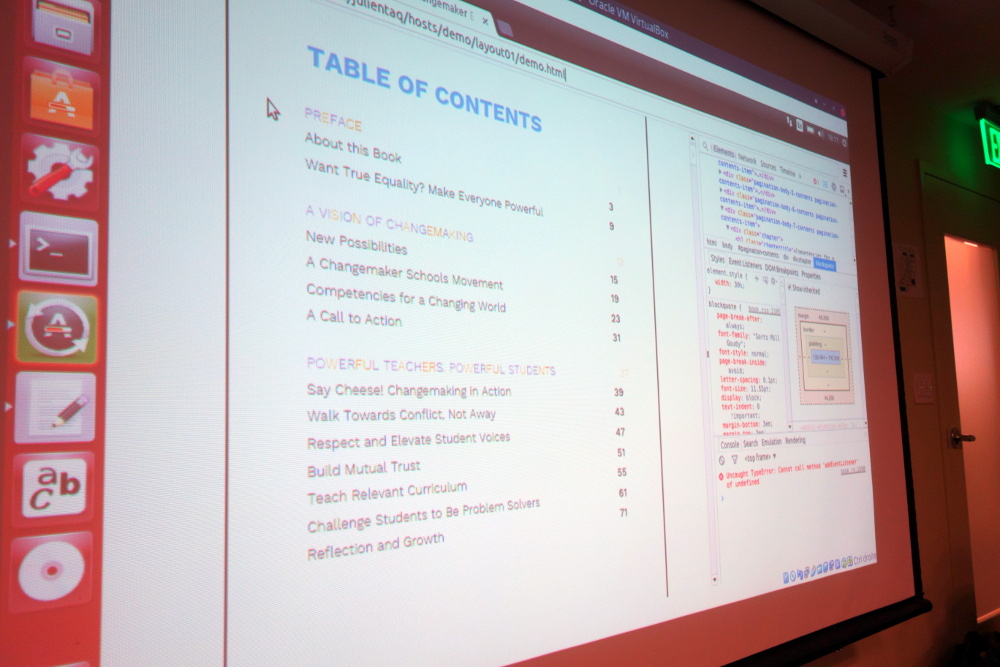

We now have general agreement on the use of CSS styled components, as well as an understanding of what a basic atom or molecule would look like, a high-level list of agreed design principles, an approach to ‘plain vanilla’ theme with org-specific overrides, and a prescribed set of common CSS variables.

You can see the embryonic documentation about design decisions here – https://gitlab.coko.foundation/pubsweet/design

So, the crew nailed down the tooling with a few things left to discuss. There are many tools in the design/UX workflow. Unfortunately, there are not many good open source tools to support open source design workflows. That is because of the limited scope of open source projects to involve designers as I mentioned above. So design has not been seen as a priority and, consequently, the tooling is not there. You can see this in GitHub and GitLab – where are the tools that support designer workflow?

Process

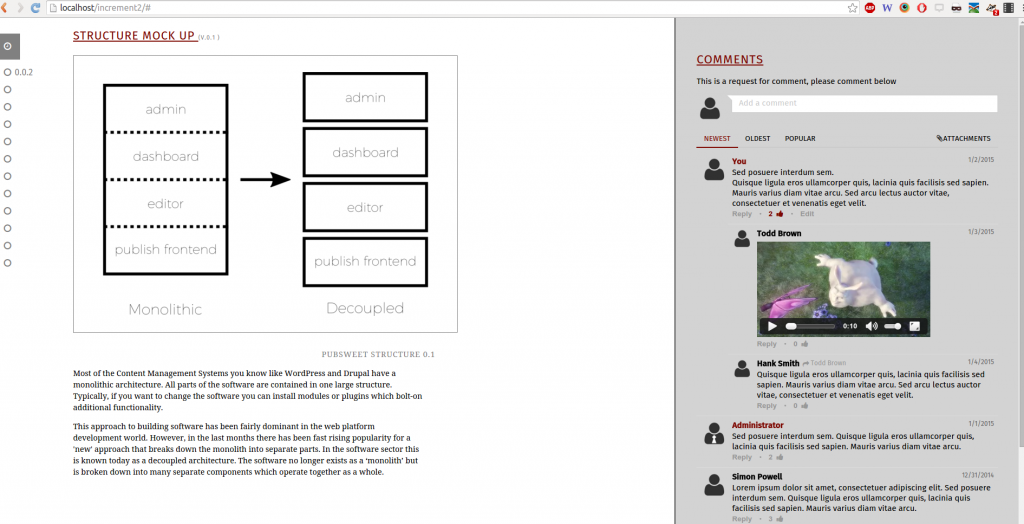

Which brings me to the final item – process. We are still working this out, but essentially each org will design components as needed, and then scope these to common established CSS variables, and then ask for feedback through Mattermost. When agreed, the component will be built and committed to the common styleguide for reuse. When the flow is established it should be a pretty fast way of working. The idea being, in essence, that atoms and molecules are developed for a target, common, ‘plain vanilla’ theme, and then each org can have their own theme that will use those common components and apply their own CSS values to the common variables.

After writing the above I asked Julien if it all looked ok, he wanted to make the following additional point about tooling and sharing design ideas and mocks:

For now, we’ve stopped the conversation at ‘let’s share svg through syncyng folders and see how it goes’.

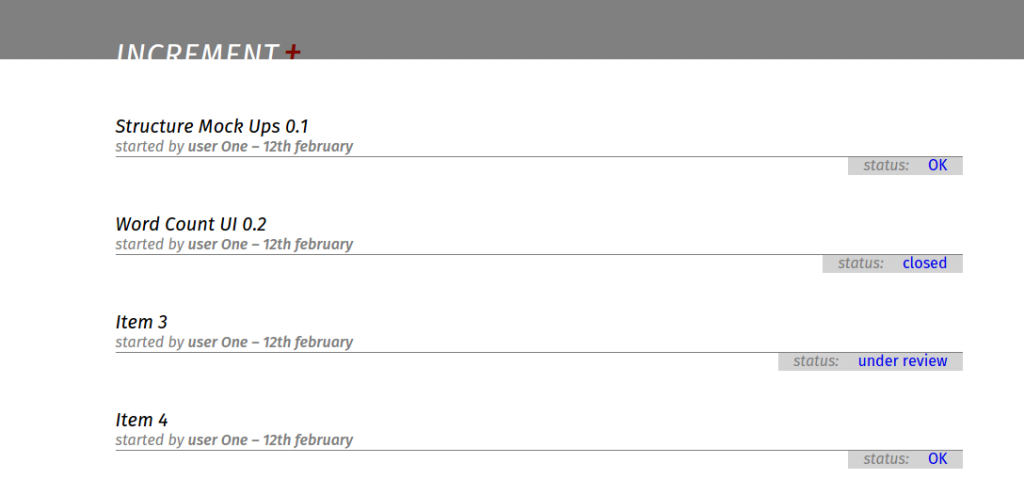

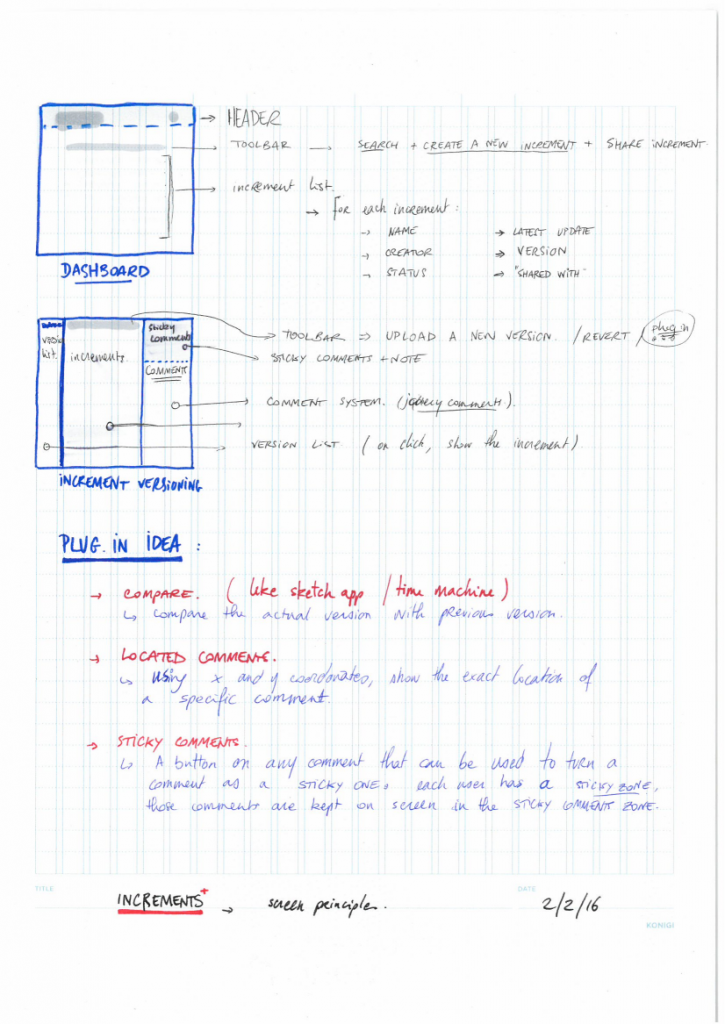

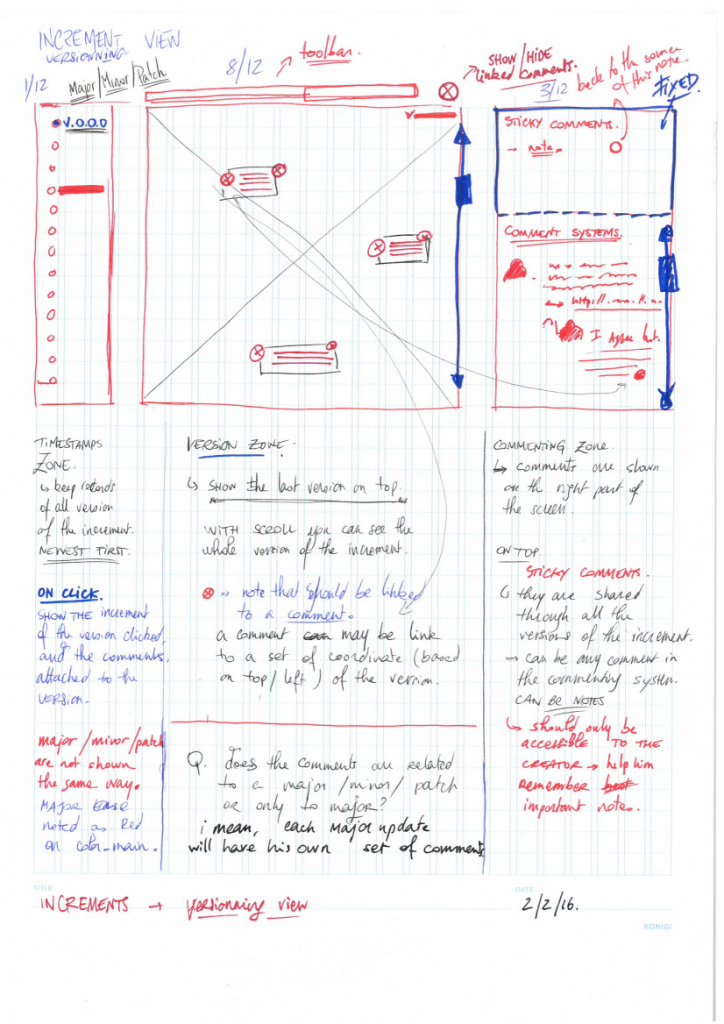

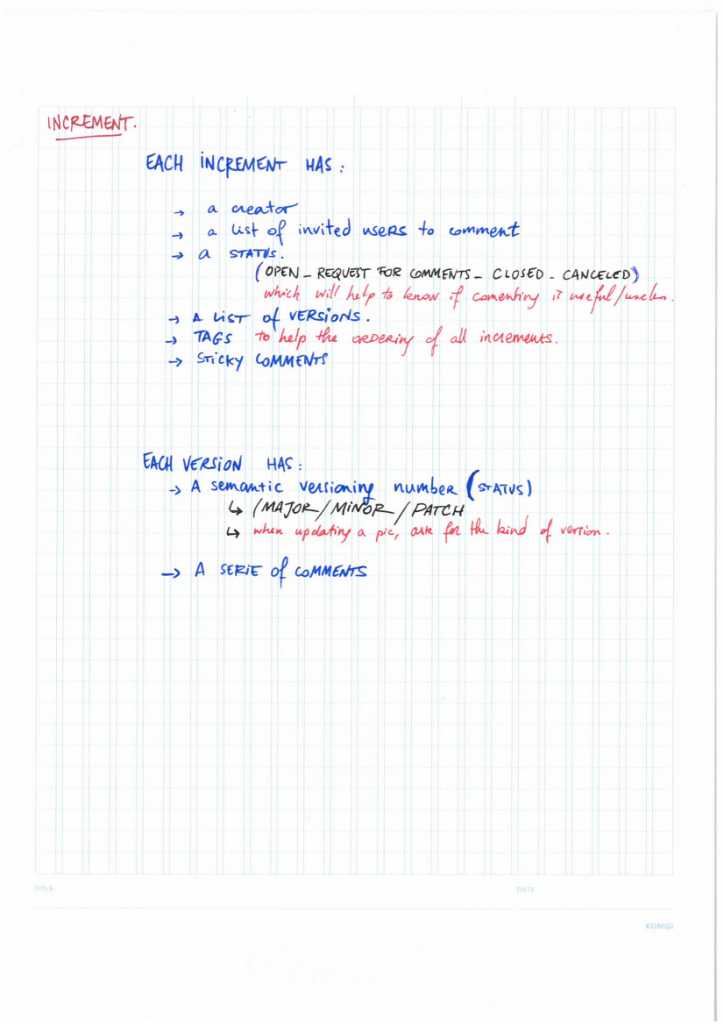

The only things that will stay in the library of components, shared for all Pubsweet apps (from Coko and others), is the code. Therefore, since there is no easy way to test mockups with different themes (which is the thing that we would need), we will end up sharing png and discussions (for which, the Increment project could be helpful: https://gitlab.coko.foundation/adam/increment).

So for now, I don’t think we can say more, specifically if we don’t want to force the user on a specific tool.

In other words, the atoms and molecules will go into the shared component library, but the mocks and discussions leading up to the creation of the components will occur elsewhere. This is because the current open source software development tools don’t support these processes (collaboration around iterative design in a live environment). Julien also makes the point that the mocks will also be shared as SVG since that allows each org to decide for themselves which environment (design software) they will use to create the mocks, so SVG, in a way, acts as an interface between the collaborating designers.

It sounds simple, but it takes time to work out simple solutions. We are also finding that there are no established models for collaborating on open source UX that we know of that we can follow… so discovery always comes with an overhead but it’s also exciting to be leading, in some small way, with creating a demonstrable real ‘in the wild’ example of how to collaborate across orgs on UX design in an open source project. That comes with its own challenges, and with its own sense of satisfaction.