At Coko we are tackling the long unsolved problem of design in Open Source. I have written a bit about this elsewhere, and it is a hard problem to solve, mainly because it is not solved anywhere – there are no good community models for this and very little discourse about the issue.

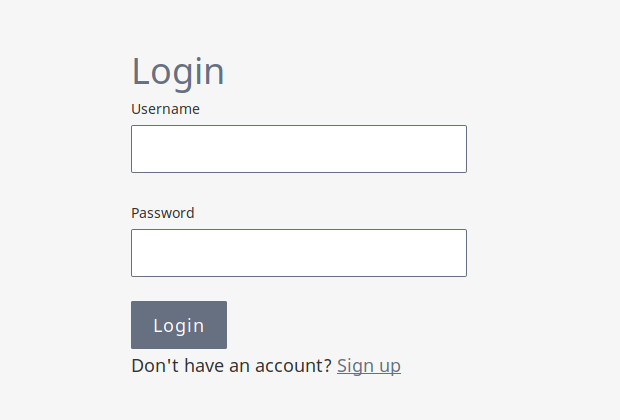

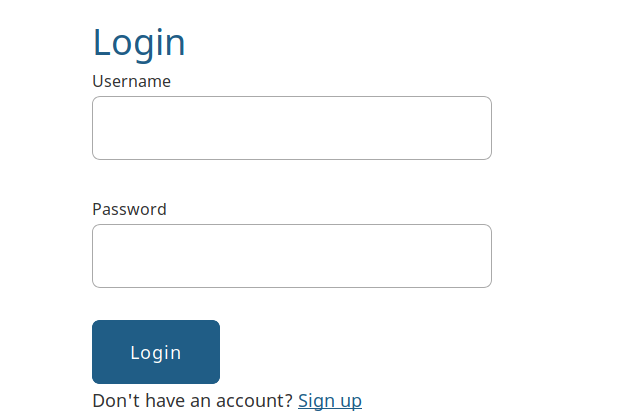

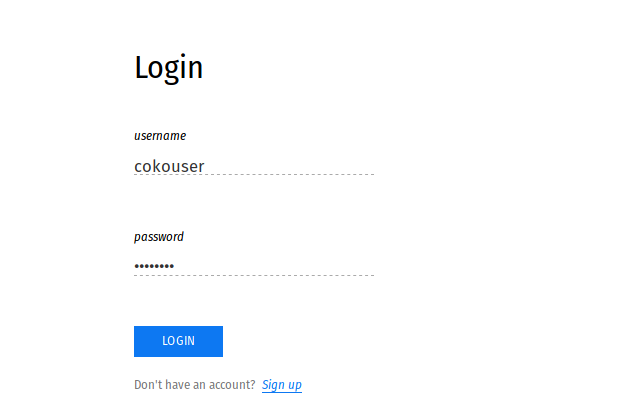

Design, of course, covers many things. I am chiefly talking about UX, although we have also solved the problem of designing for users by getting users (I prefer to call them ‘use case specialists’) to design their own systems. But this is not about that. I want to talk just about community processes for UX that will yield common best practices, while also enabling each organisation to realise their desired aesthetics ie achieve the look and feel they want that best reflects their organisation. As reflected in the following screenshots of xpub-Hindawi, xpub-eLife, and xpub-collabra:

There are several mechanisms that we have employed to achieve this. The first is that we have ‘elevated’ design to the same level of value in the community as code. I say ‘elevated,’ not because we had to raise its value in the Coko community, but rather the estimation of the value of design in the open source community at large is very low. So, against this, as a baseline, at Coko we have chosen to value design more than in your typical open source project. Also, I don’t want that to imply there are other disciplines in the software development process that do not rank as highly as these two – documentation, feedback, testing and so on… these are all equally valued alongside design and code, but for now I want to focus just on UX design.

To ‘elevate’ design, it took just the simple step of stating it to be so. As the co-founder of this community I have some sway over the direction and form of the culture. So I cashed out some of this capital to make a very simple statement when I was facilitating a community meeting that we must value design as much as we value code. It was this simple statement that set a placeholder for building processes that put design in the value-center of the community.

Next, when there was a call for more processes to assist communication across the various orgs, I made sure we had two work groups which each consisted of one person from each collaborating organisation. These two foundational WorkGroups were the Dev WorkGroup and the Design WorkGroup.

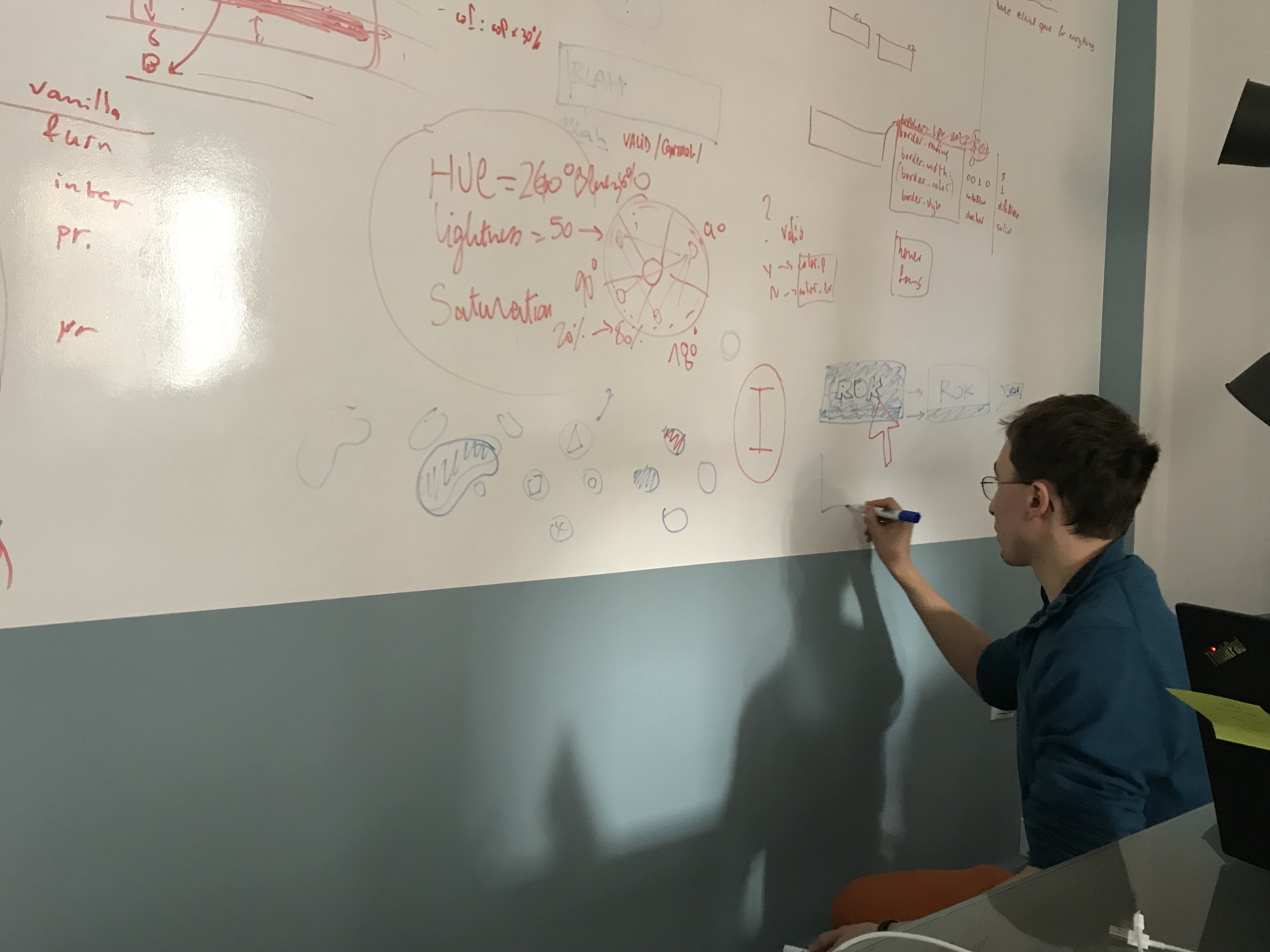

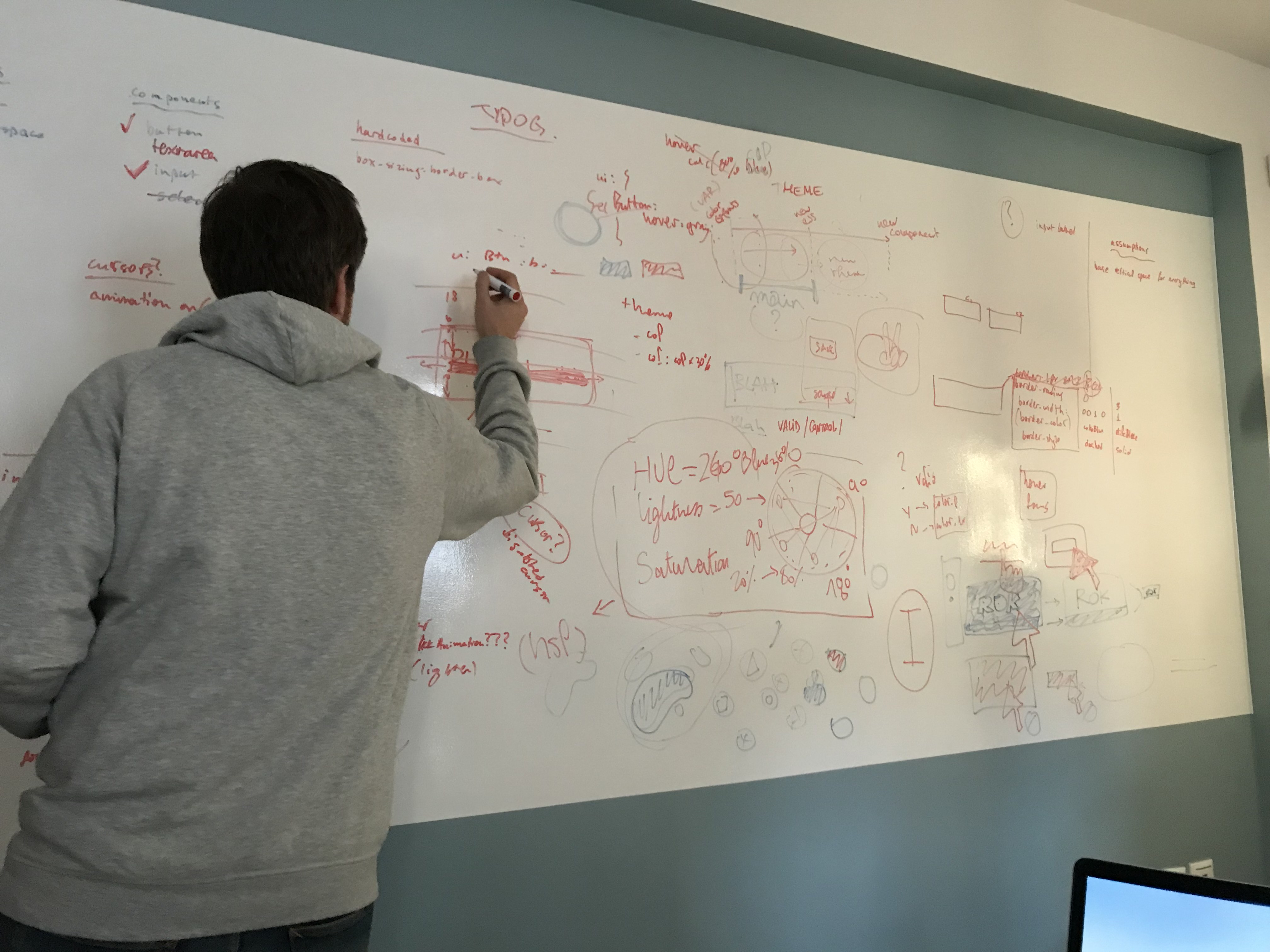

The Design WorkGroup then went ahead and started discussing how we might contribute to a platform where each org could have the look and feel they wanted. It was a process of first understanding the problem and then working through possible solutions. It was necessarily like this, a process of discovery before implementation, because there are not very many established or discussed processes like this in the open source world that we could follow (as mentioned above). So we have to discover the problem, and then invent a solution.

The problem boils down to small levels of abstraction. Interfaces are, after all, made up of many small parts. The problem therefore resided in how to account for different stylistic approaches to, what we now call, atoms (see Brad Frost’s article on Atomic Design), and how atoms fit together to form ‘molecules’ ie. we needed a level of abstraction that would allow any org to have the look and feel they wanted for an (eg) button, and also how that button was situated with other elements.

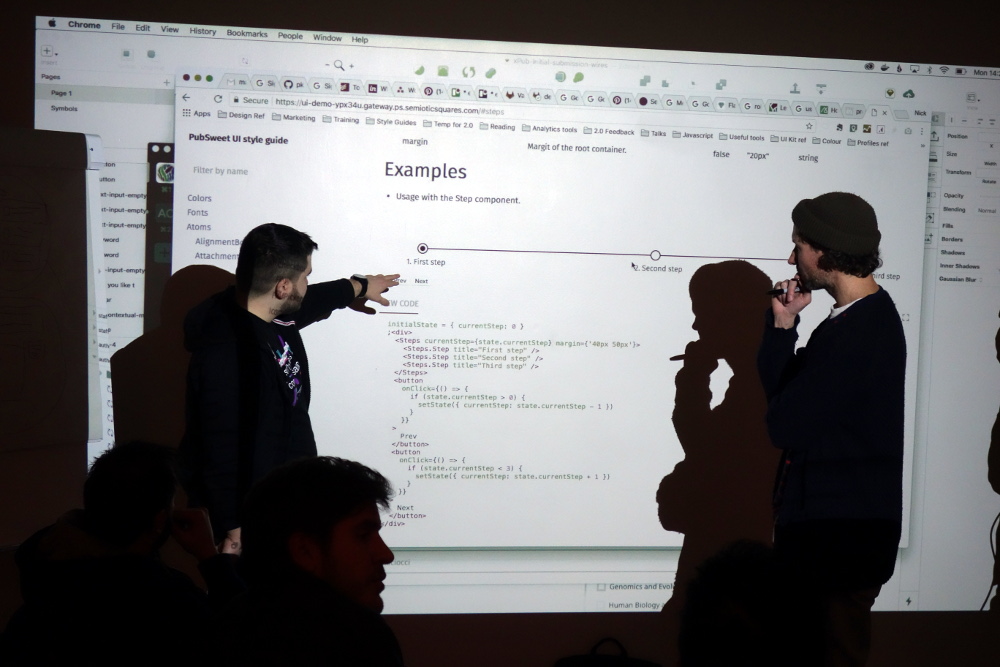

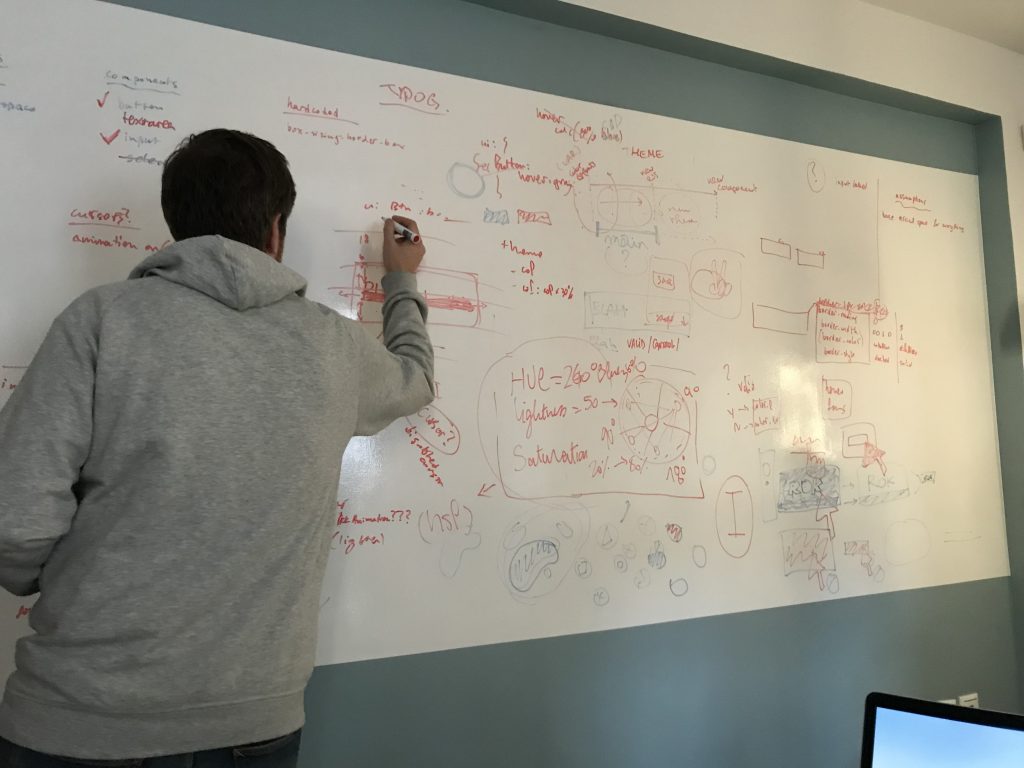

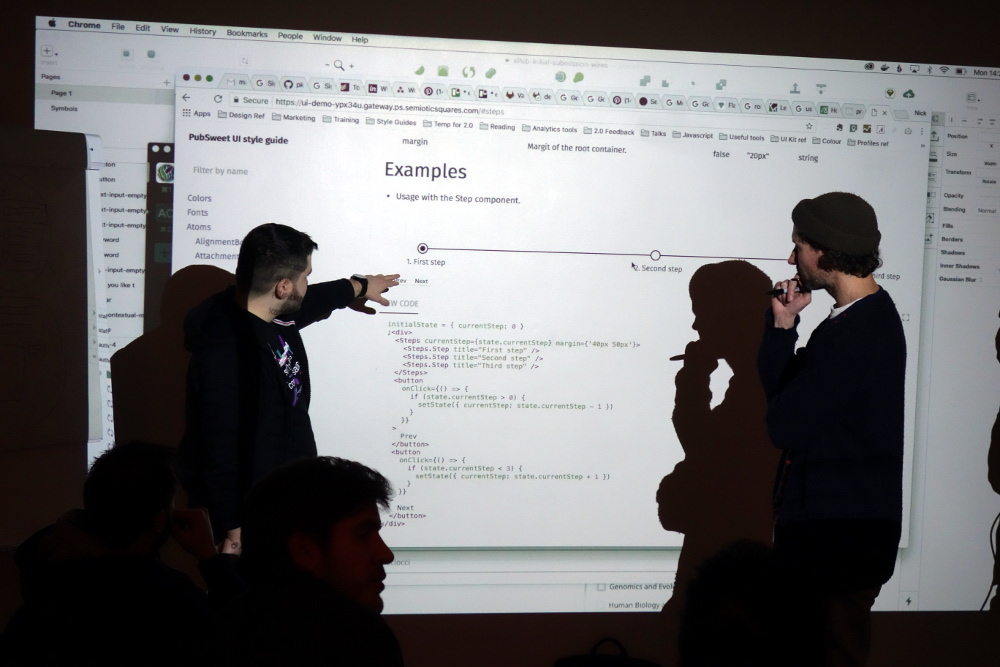

Julien Taquet (Coko) and Nick Duffield (eLife) met with Yannis Barlas (Coko) in Athens for three days to thrash this out.

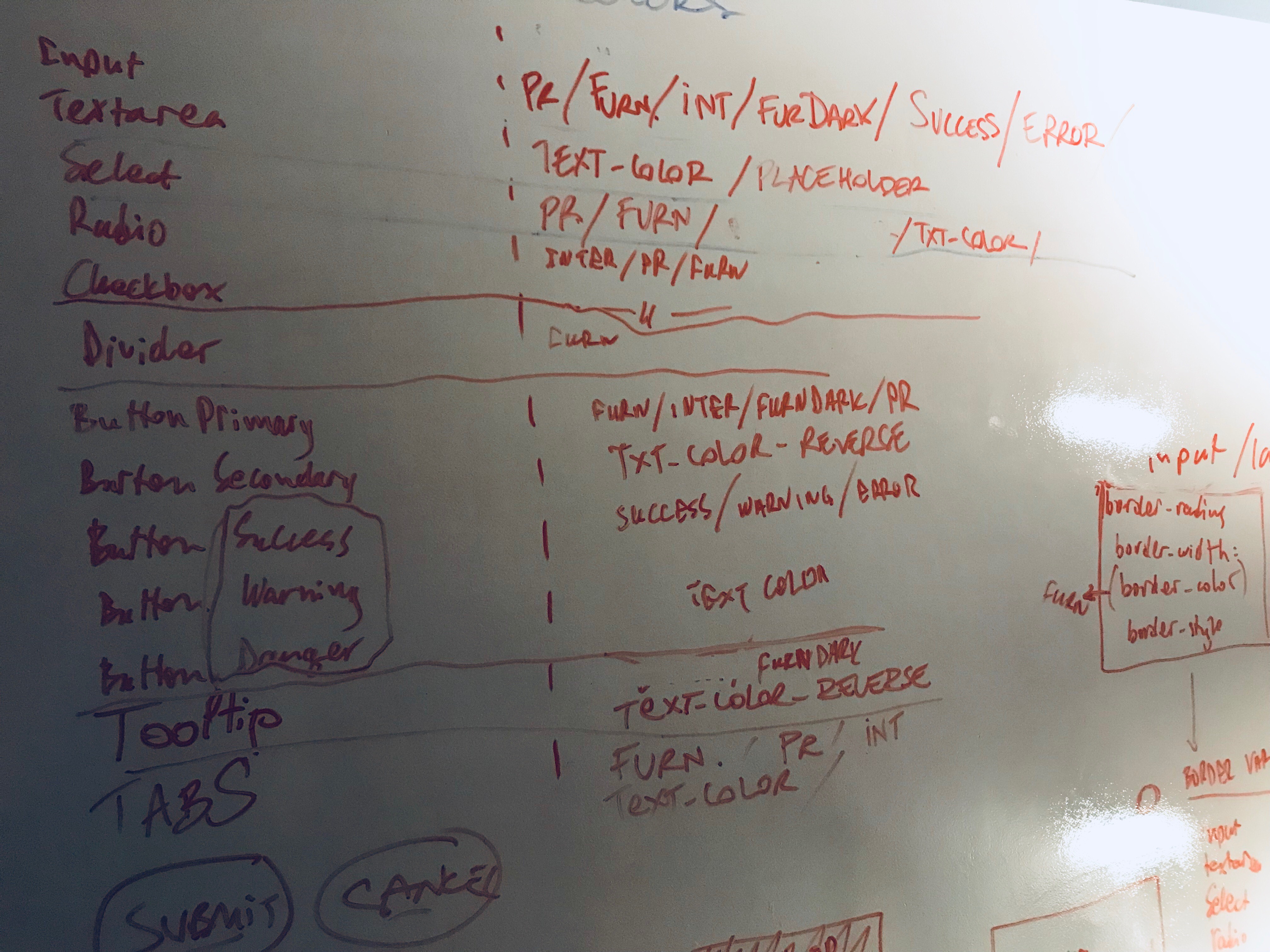

They came up with an agreed common set of standardised CSS attributes per UI element, and associated reusable CSS variables that could be used across any UX element.

You can see these lists here…

- Color Variables

https://gitlab.coko.foundation/pubsweet/design/issues/1 - Typography Variables

https://gitlab.coko.foundation/pubsweet/design/issues/2 - Form Variables

https://gitlab.coko.foundation/pubsweet/design/issues/3 - Spacing Variables

https://gitlab.coko.foundation/pubsweet/design/issues/4

That is the simple starting point. In effect, this means that if any organisation designs a feature using UI elements (eg a login form) they can use these shared style names and populate them with their own values. This means another org’s stylesheet will apply equally well to inherited/reusable components as it does to the ones they build themselves.

Which seems simple: it is… but understanding the problem space, and where the commonality lies, was half the battle.

The group has now also identified a common set of UI elements that can be reused and are iterating through this list, designing them as they go. See https://gitlab.coko.foundation/pubsweet/design/issues/21

This is required because even the simplest UI element may have several contexts it has to account for. Take the example of a ‘simple’ button, one of the simplest UI elements of them all…. however, there are actually 5 different button states that must be accounted for – the default state, active, hover, pressed and disabled. In each case, the style variables must be applied appropriately. See here for more information – https://gitlab.coko.foundation/pubsweet/design/issues/19

So, it’s not quite as easy as it might first seem.. the good news is that the teams are very committed to working through these issues, as without doing this groundwork, components are really not reusable.

The result is you can grab components that another org has made, be it a page-based component (eg. Dashboard), or a molecule (eg a Staff Assignment dropdown) and plug it into your system and it will look like it is part of your system.

We are making good progress on all of this, including now integrating common best practices for accessibility into the design process. Also, since this groundwork has come quite far, new orgs joining the Coko community can benefit a lot from the work already done and pick up components from the shared/common UX stylebook and integrate them… pretty cool….