I recently went over some publishing systems with Yannis and Christos from Coko. We looked at various systems and discussed them. As we did this, I realised that I’d actually built quite a few! Although we weren’t just talking about those I had built, I began to think through what I had done right and wrong when building those earlier systems. Each development is a learning process and you will always get things both wrong and right at the same time. The trick is to get less wrong the next time round…

In the ten years that I have been building these systems, I have worked with some pretty talented people, including Luka Frelih, Douglas Bagnall, Alexander Erkalovic, Johannes Wilm, Remko Siemerink, Juan Gutierrez, Lotte Meijer, Fred Chasen, Michael Aufreiter, Oliver Buchtala, Nokome Bentley, Andi Plantenberg, Mike Mazur, Rizwan Reza, Gina Winkler and many others including the entire team of Coko – the most talented bunch of them all. Coko team:

Kristen Ratan – CoFounder, San Francisco

Jure Triglav – Lead PubSweet Developer, Slovenia

Richard Smith-Unna – PubSweet Developer, Kenya

Yannis Barlas – PubSweet Frontend Developer, Athens

Christos Kokosias – PubSweet Frontend Developer, Athens

Charlie Ablett – INK Lead Developer, New Zealand

Wendell Piez – XSL-pro, East Coast USA

Julien Taquet – UX-pro, France

Henrik van Leeuwen – Designer, Netherlands

Kresten van Leeuwen – Designer, Netherlands

Juan Guteirez, Sys Admin, Nicaragua

Alex Theg – Process, San Francisco

All systems except, unfortunately, one (see below) are open source.

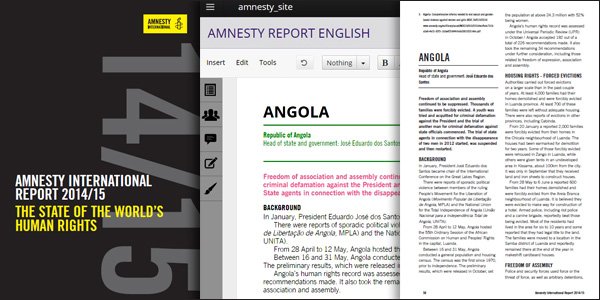

FLOSS Manuals

The first publishing system I designed and built didn’t have a name really. It was the glue behind the FLOSS Manuals English site. FLOSS Manuals was, and is still, a community focussed on building free manuals about free software. I started the development in English but the system needed to be useful to a number of different language communities, of which Farsi was the most interesting. Today, only the French and English communities are still operational.

I built the FLOSS Manuals system in Amsterdam in about 2006. It was based on TWiki, an open-source Perl-based wiki. I chose TWiki because back then it was the only wiki around that had good PDF-generation support – I think this came from some of its plugins. TWiki had a good plugin and template system and I came to think of it as a rapid prototyping application – it was pretty malleable if you knew how. I was a crap programmer so I cut and pasted my way to a system that became usefully functional.

I leveraged the account creation and permission systems of TWiki, and ripped out the wiki markup editing and replaced it with an HTML WYSIWYG editor (I think it was TinyMCE). So in wiki world terms I had committed something of a crime. Throwing out wiki markup at the time was unheard of in the post-2004 euphoria of Wikipedia. But JavaScript WYSIWYG editors were coming along just fine, and I thought wiki markup no longer made any sense (in fact it had been invented to make making HTML easier than writing raw HTML). But y’know… wiki markup was no easier than using a WYSIWYG editor, despite the sacred status of Wiki markup in the Wikimedia community. And despite my heresy,the Wikimedia did give me a barnstar for my efforts, which was nice of them:)

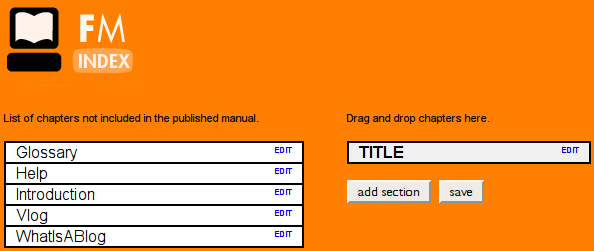

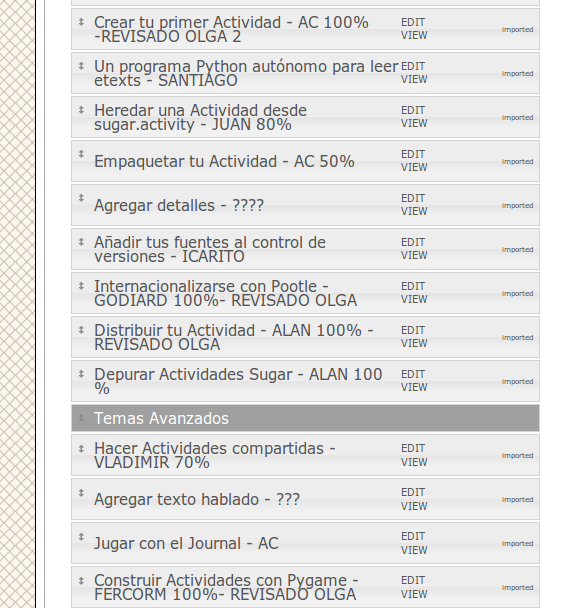

After I reached the limit of my coding skills, a friend, Aco (Alexander Erkalovic), helped build the next bits. I found some money to pay him and that is when things started to move forward. I can’t remember all parts of the system, although it’s still in up and running for some FLOSS Manuals language sites. The core of the system was the manual overview page. This contained a list of all chapters in a manual. You could also set the status, add new chapters, view overall progress etc. from this one page. We had a separate mechanism for creating an ordered table of contents (index) for a manual.

Index builder, essentially a dynamic drag and drop mechanism for arranging chapters

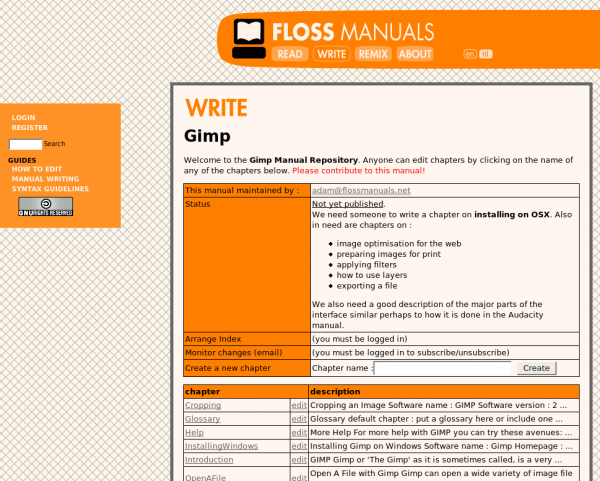

The overview page

Essentially, you added a chapter on the overview page and then opened the index builder and arranged the chapters. When saved, the (refreshed) overview page displayed the correct (new) order of chapters. We had to do it like this because back then, in the era of the ‘page refresh,’ it wasn’t possible to synchronise dynamic elements across multiple clients. So we couldn’t have one ‘shared’ index builder that would dynamically update all user sessions simultaneously. Nevertheless, it worked pretty well.

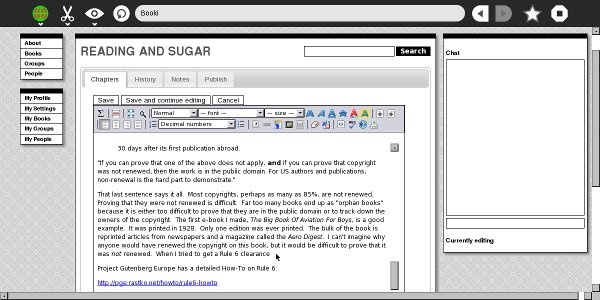

From the overview page, you could choose a chapter to edit. When you did so, you locked the chapter and, through some JS trickery Aco cooked up, we wereable to do this across multiple clients so everyone could see in real time who was editing what.

When editing a chapter, you could save the document and then, when ready, publish it. This way you could have an ‘in progress’ state of a chapter and a published state. At publish time the chapter was copied across to the system’s web delivery cache.

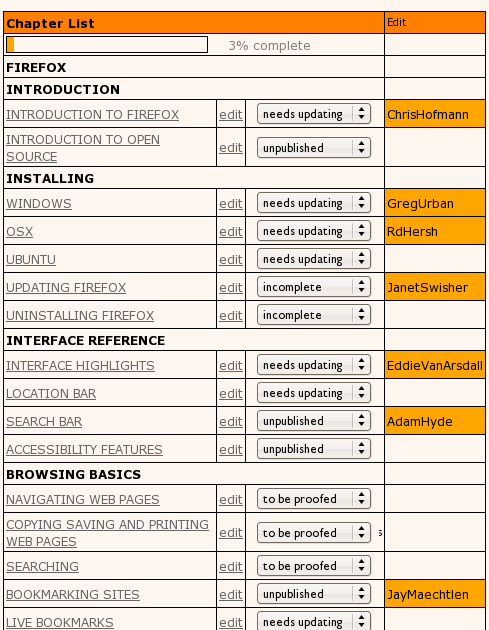

We also added chapter status markers, as you can see from the above image. It was pretty basic but nifty.

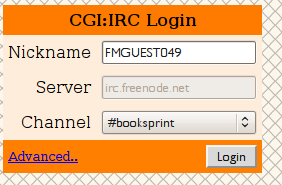

Next I hacked in a live chat, initially using IRC (freenode) for a global FLOSS Manuals-wide chat:

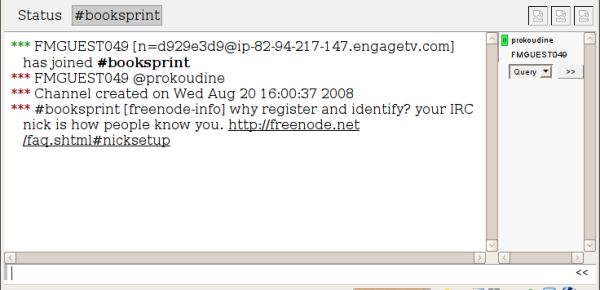

Then I hacked a fancy AJAX script into the chapter edit interface so each manual could have its own chat with the interface present while you were editing a chapter. It also looked a little nicer than the IRC channel. From the beginning, I tried to make everything look like it was meant to be there, even if it was a fiddly hack.

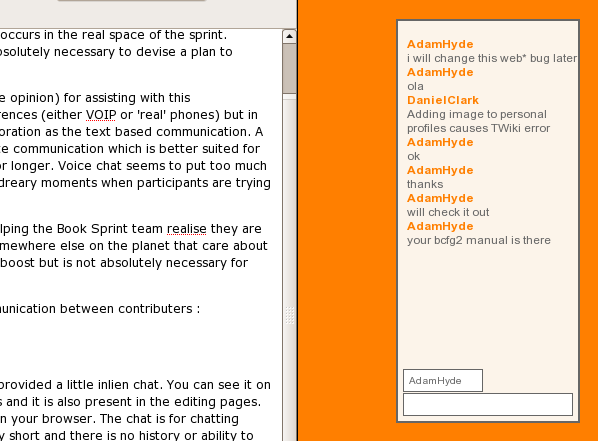

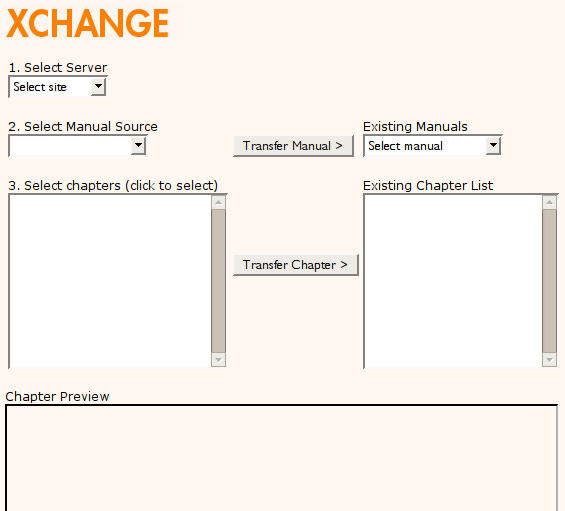

FLOSS Manuals also had a lot of other interesting goodies. We had federated content, for example. This was established so one language site could import an entire manual from another and set up a translation workflow.

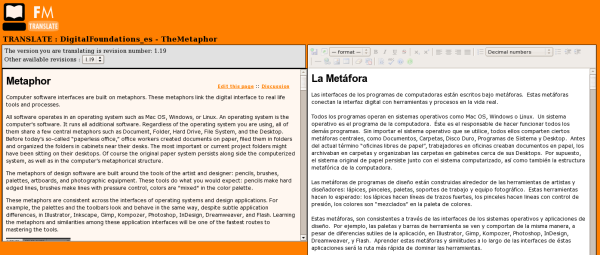

We also had a simple side-by-side editor set up for translation that worked pretty well for translators.

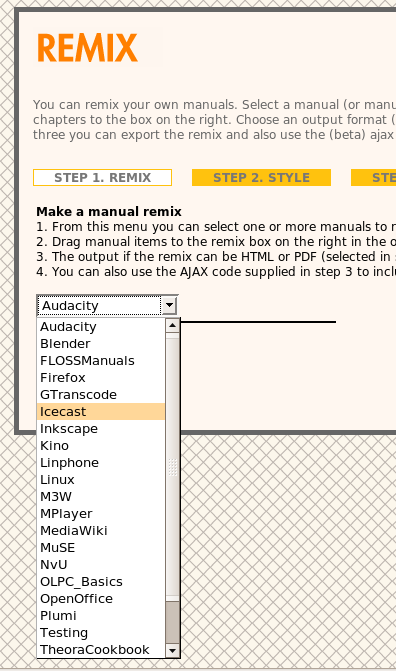

In addition, we had a remix system for generating new versions using mixed content from other manuals. This was useful for workshops and for making personal manuals, for example.

In addition, we had a remix system for generating new versions using mixed content from other manuals. This was useful for workshops and for making personal manuals, for example.

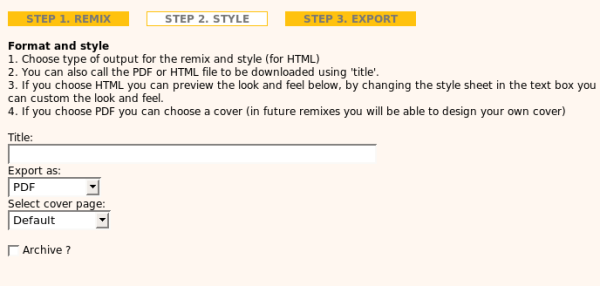

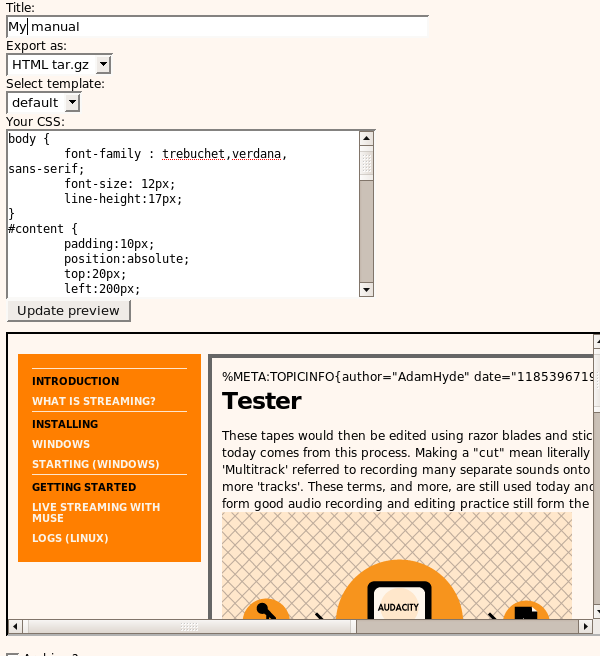

One of the cool things about the remix is that you could output in many formats such as PDF and zipped HTML, add your own styles through the interface, PLUS you could embed the remix in your own website 🙂 The embed worked similarly to methods used today to embed YouTube or Vimeo videos in websites (by cut and pasting a simple snippet). The page delivery was ‘live,’ so any updates to the original manual were also displayed in the embed. I thought that was pretty cool. No one used it of course 🙂

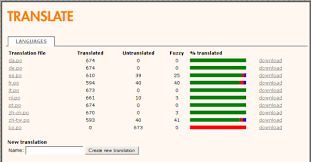

The system also had diffs so you could compare two versions of a chapter. It was good for seeing what had been done and by whom. In addition, it was possible to translate the user interface of the entire system to any language using PO files and a translation interface we custom built:

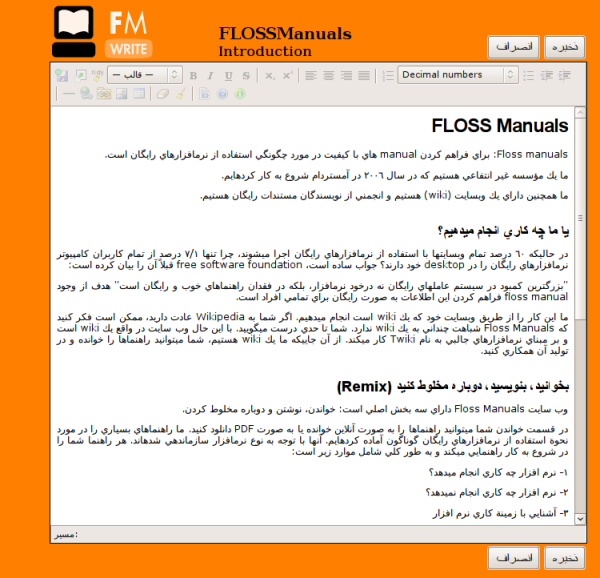

But by far the most interesting thing for me was building FLOSS Manuals to support Farsi. It was interesting because, at the time, no PDF-renderer I could find would do right-to-left rendering. Behdad Esfahbod advised me to just use the browser to do it. Leslie Hawthorn from Google Open Source Programs Office introduced me to him after I went on a naive search in the free software world for ‘someone that knew something about RTL in PDF’. I was very lucky. The guy is a generous genius. He just suggested an approach a new way to think about it and later I worked with Douglas Bagnall (see below) to work out how to do it. The basic idea being that HTML supported RTL and the PDF print engines rendered it nicely…so…it was my first realisation that the browser could be a typesetting engine.

But by far the most interesting thing for me was building FLOSS Manuals to support Farsi. It was interesting because, at the time, no PDF-renderer I could find would do right-to-left rendering. Behdad Esfahbod advised me to just use the browser to do it. Leslie Hawthorn from Google Open Source Programs Office introduced me to him after I went on a naive search in the free software world for ‘someone that knew something about RTL in PDF’. I was very lucky. The guy is a generous genius. He just suggested an approach a new way to think about it and later I worked with Douglas Bagnall (see below) to work out how to do it. The basic idea being that HTML supported RTL and the PDF print engines rendered it nicely…so…it was my first realisation that the browser could be a typesetting engine.

Implementing RTL in the FLOSS Manuals system was so very tricky, and I was unfortunately on my own for working out Farsi regex .htaccess redirects and other mind-numbing stuff. Just trying to think in right-to-left for normal text did my head in pretty fast, but somehow I got it working.

Outputs of all language books were PDF and HTML, later also EPUB. I initially used HTMLDoc for HTML-to-PDF conversion. It was pretty good but didn’t really think like a book renderer needs to. This was my first introduction to the overly long wait for a good HTML-to-PDF typesetting engine. Later I found some money and employed Luka Frelih and then Douglas Bagnall to make a rendering engine separate from the FLOSS Manuals site (see Objavi below). Inspired by my chats with Behdad (above) Douglas introduced some clever PDF tricks with the Webkit browser engine to get book formatted PDF from HTML. I can’t remember exactly how he did it but essentially he used xvfb frame buffer to run a ‘headless browser’. In short, and for those that don’t know those terms, he came up with a very clever way to run a browser on a server to render PDF. It did it by rendering HTML to PDF in pages (using the browser PDF renderer) and then rendered another set of slightly larger blank PDF with page numbers etc and embedded one within the other. Wizard. Hence we were able to make PDF books from HTML. It also supported RTL 🙂 I think I need to say here that this whole process was immensely innovative and we did it on a dime. Also, because we refused to use proprietary systems we were forced to innovate. That was a very good thing and I welcomed the constraint and the challenge.

Later we also used WKHTMLTOPDF to make PDF. It worked and we worked with that for a long time. I even tried to start a WKHTMLTOPDF consortium with Jacob Trulson, the founder of the project, it got some way but not far enough (I am very happy WKHTMLTOPDF is still going strong!).

I played a lot with Pisa and Reportlab for generating PDF and finally cracked it when I started book.js (more on this below). Actually, when it comes down to it I think I used everything that wasn’t proprietary to make book formatted PDF from HTML. It was the start of a long love affair with the approach. I promoted this approach for a long time, even calling for a consortium to be formed to assist the approach:

http://toc.oreilly.com/2012/10/the-new-new-typography.html

http://toc.oreilly.com/2012/11/gutenberg-regions.html

As it happens, all this time later I’m still doing the same thing 🙂

http://www.pagedmedia.org

We integrated FLOSS Manuals with the Lulu API (now defunct). This allowed us to generate books automatically from HTML using Objavi (below) and they would be automagically uploaded to the Lulu print-on-demand marketplace for sale…that was amazing! Ah…but also no one used it. Lulu shut down the API as soon as they realised no one was using it.

We made many many manuals with this setup. Many of them printed from the auto-PDF magic and were distributed as paper books. Many of the books were in Farsi. The One Laptop Per Child community even built a FLOSS Manuals app that was distributed on all OLPC laptops with the documentation made with FLOSS Manuals.

The system produced loads of manuals and printed books about free software. All free content.

The FLOSS Manuals platform didn’t have a name. It was a hack of TWiki. While you could get all the plugins online, it would have been a nightmare to deploy. I did deploy it many times but I essentially copied one install to another directory and then cleaned out all the content and user reg etc. and went to town rewriting all the .htaccess redirects. It sounds stupid now, but I spent a lot of time doing URL redirects to ditch the native TWiki URLs (which were extremely messy) and make them readable. Hence the system was a pain to deploy or maintain. It was feeling like we needed a standalone, dedicated, system….

Booki

Booki was the next step. It was clear we needed something more robust and also it was clear no web-based book production system existed, hence the hackery Twiki approach. So it was about time to build one. At the time, though, I remember it being very difficult to convince anyone that this was a good idea. I didn’t have access to publishers, and everyone else thought books were just soooo 1440. What they didn’t realise is that we were building structured narratives and that, IMHO, will have a lot of value for a long time. Call it a book or not. Anyway, we built Booki on Django (a Python framework) and the first time we used it was a Book Sprint for the Transmediale Festival in Berlin.

Aco literally would be building the platform as it was being used in the Book Sprint – restarting when everyone paused to talk. It was an effective trick. We learned a lot working with the tool and building it as it was being used.

At the time I couldn’t imagine book production being anything other than collaborative. FLOSS Manuals collaboratively built community manuals. Book Sprints were short events building books collaboratively. So Booki was meant to be all about collaboration. Booki also was run as a website (booki.cc) which was freely available for anyone to use.

Many groups used it which was cool.

Booki.cc run from with the OLPC laptop

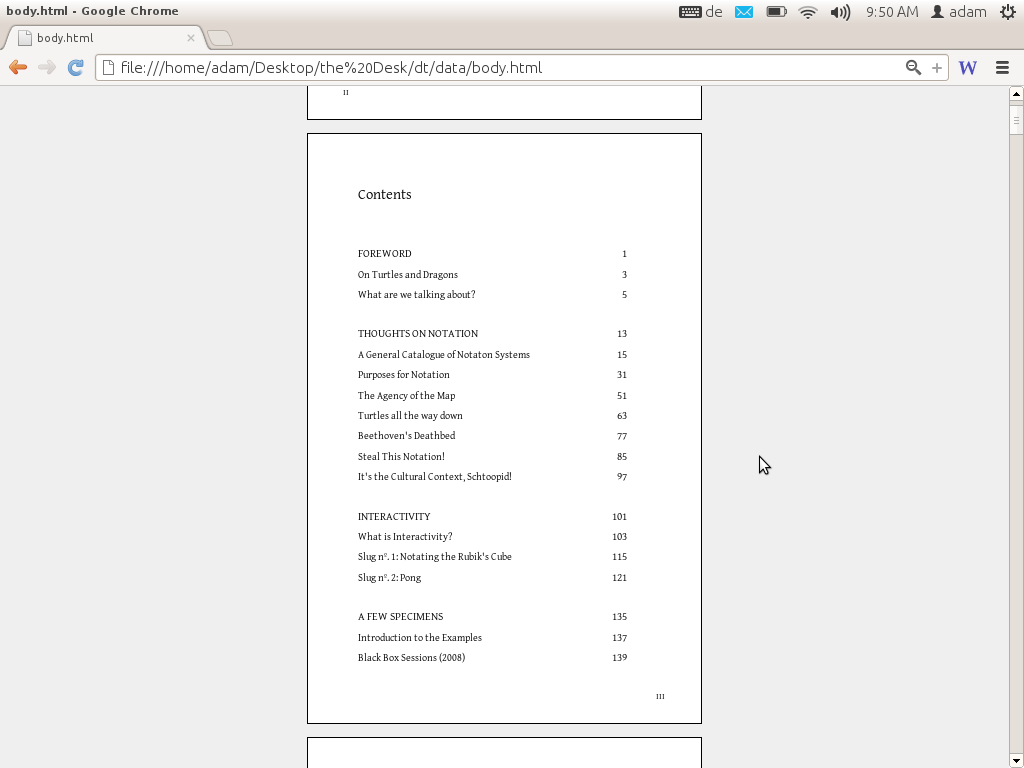

Booki had all the basic stuff the FLOSS Manuals system had and we advanced the feature set as our needs became more sophisticated, but the basics were really the same.

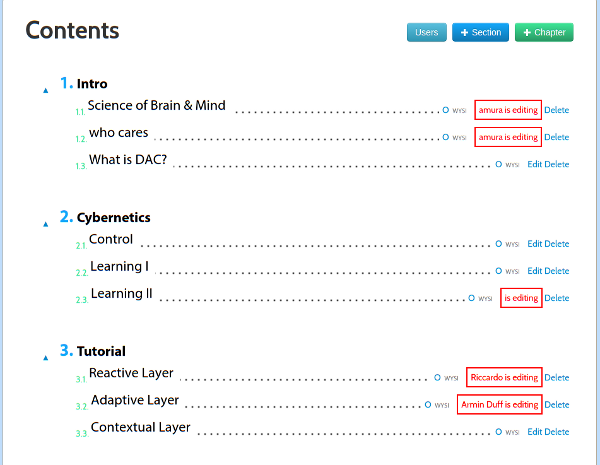

The main differences were that we had a dynamic ‘table of contents’ where you could add and rearrange chapters etc and the updated ToC would be dynamically updated across all user sessions. Hence the ToC became a kind of ‘control panel’ for the book.

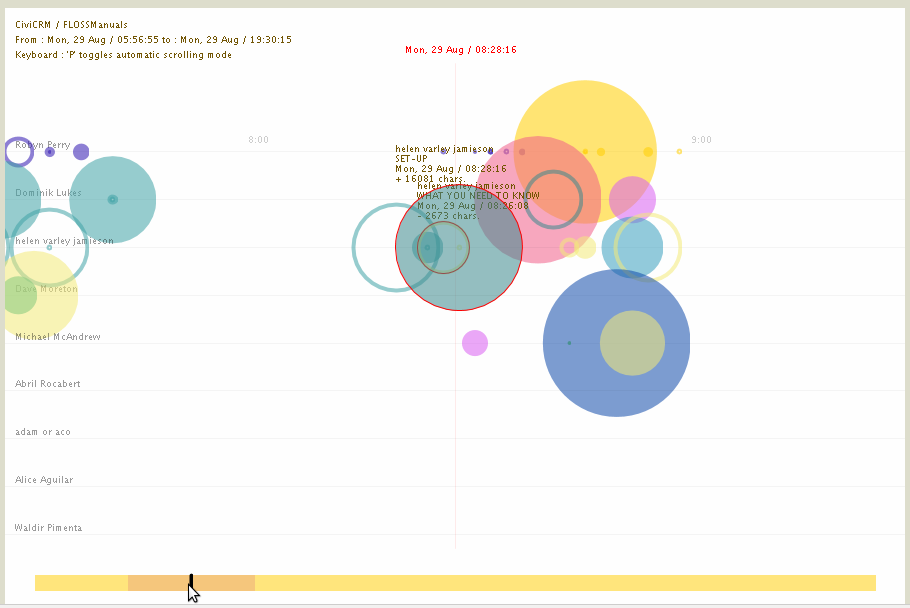

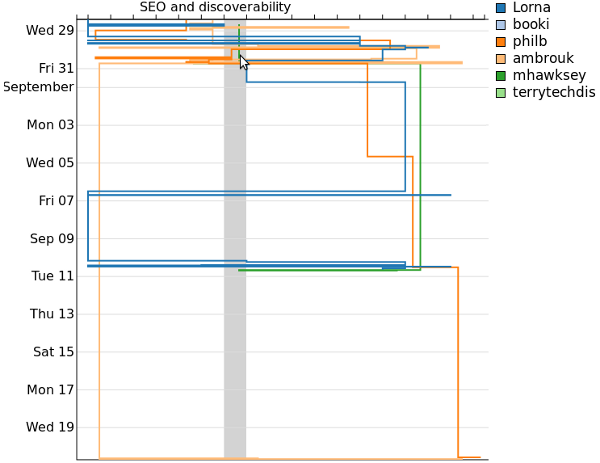

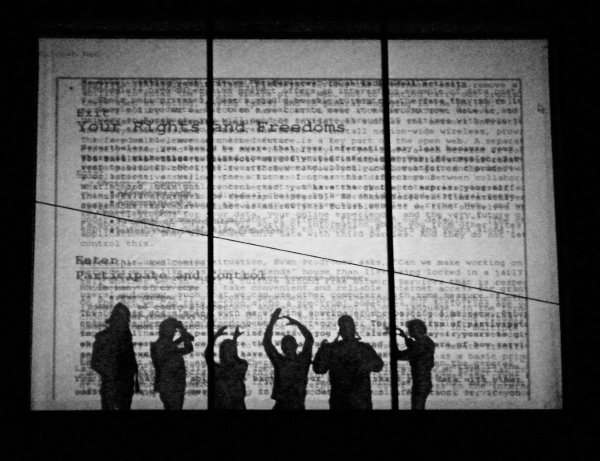

We also experimented with data visualisations of book production processes.

We did some cool stuff with the visualisations. For example, during the Open Web Book Sprint (also in Berlin) we worked in the Hungarian Embassy. They had a huge window that you could backwards project onto so people could see the projections on the street. So we made a visualisation of text from the book being overlayed as we wrote it. Below is an image shot with us standing in front of the projector…I mean..c’mon…how cool is that? 🙂

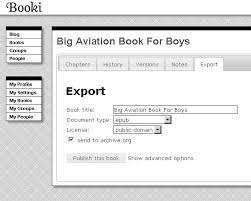

Booki also had federation. You could enter the target URL of a book from another install and Booki 1 would make a portable archive (booki.zip) and send it to Booki 2. Booki 2 then unpacked the zip and populated the book structure complete with images etc. I liked the idea very much of using EPUB instead as a transport technology instead and was later able to do so for Aperta and PubSweet 1 (see below).

In general, Booki didn’t advance much further from the FLOSS Manuals set up. It kind of did ‘more of the same’. I think the only stuff that went further than the previous system was the dynamic table of contents plus it was easier to install and maintain. Having groups was also new, but that wasn’t used much. It was in some ways just a slightly different version of the previous system.

Booki was also used for producing a tonne of books.

Objavi 1 & 2

Alongside the development of the FLOSS Manuals system and Booki, I headed up the development of Objavi. Objavi is basically a separate code base that was used as a file conversion workhorse. Objavi 1 was a little bit of a hacky maze but it did a good job. It would basically accept a request and then pipe that through a preset conversion pipeline. It did a good job. What I found most useful from this is that each step left a dir that I could open in a browser to inspect the conversion results. So if the conversion needed several steps, this was very helpful in troubleshooting.

Objavi 2 was meant to be an abstraction. However I don’t think it really got there, and Booki, which later became Booktype, came to internalise these conversion processes after I left the project. I always thought internalising file conversion was a bad idea because file conversion is resource-intensive, making it better to throw it out to another external service. And having a separate conversion engine enables you to completely overhaul the book production code without changing the conversion code. Hence FLOSS Manuals could migrate to Booki but still use the same external conversion engine. This was a HUGE advantage. Further, all the FLOSS Manuals instances, as well as booki.cc could use a single Objavi install for their conversions.

Objavi was actually also the magic behind the federated content in both the FLOSS Manuals system and Booki. All content would be passed through Objavi for import and export so Objavi became the obvious conduit for passing a book from one system to another. This gave me a lot of ideas about federated publishing which I have written about elsewhere and archived here.

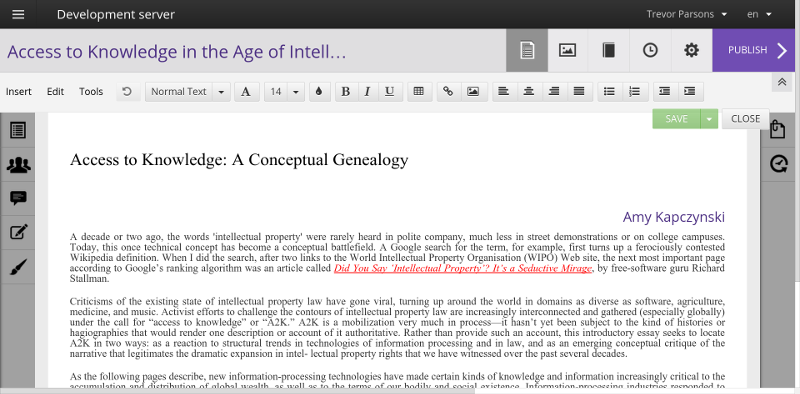

Booktype

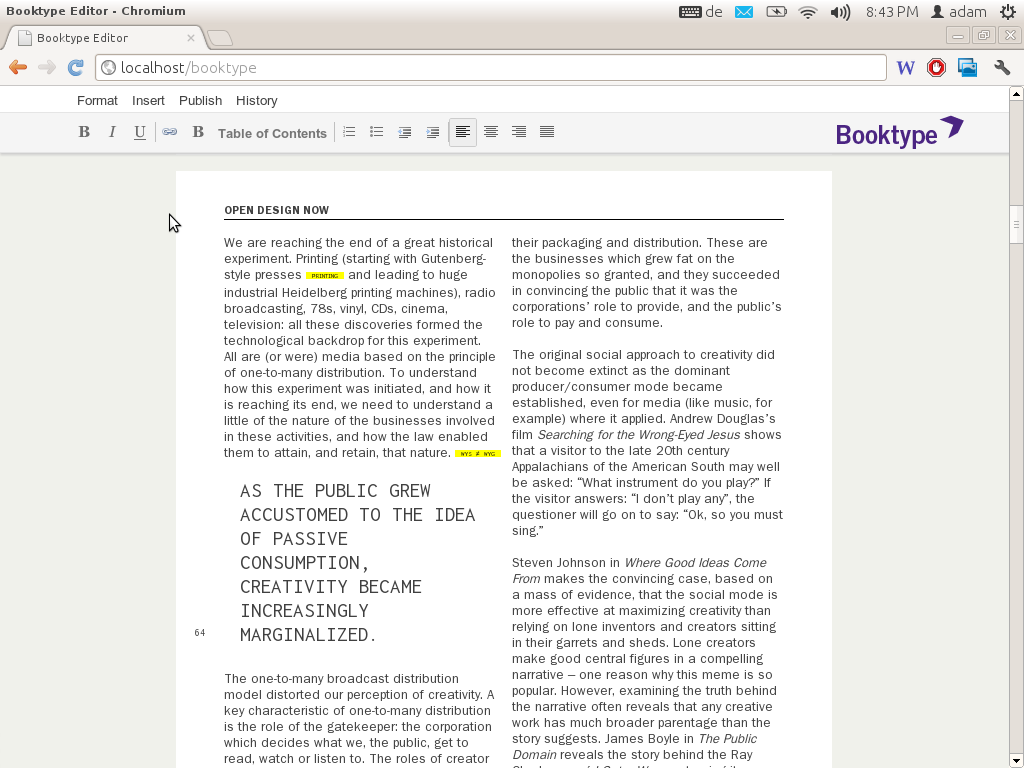

Booktype was really Booki taken to market. I was frustrated by not getting much uptake, so I took Booki to Sourcefabric in Berlin and headed up the development there. Booktype gained a UX cleanup. The editor was changed after an event I organised in Berlin called WYSIWHAT. The event was meant to catalyse energy around the adoption of a shared editor for many projects. It was of many things I did in pursuit of the perfect editor. At that event, we chose the Aloha contenteditable editor. I don’t think that was as useful a change as expected at the time, but back then contenteditable looked like the way to go despite there being few editors that supported it. Since then TinyMCE, CKEditor and others all have contenteditable support, further econtenteditable became a bit of a lacklustre implementation in browsers.

Booktype was literally the same code as Booki but rebranded. So many of the same features persisted for quite some time until Booktype eventually took on a life of its own.

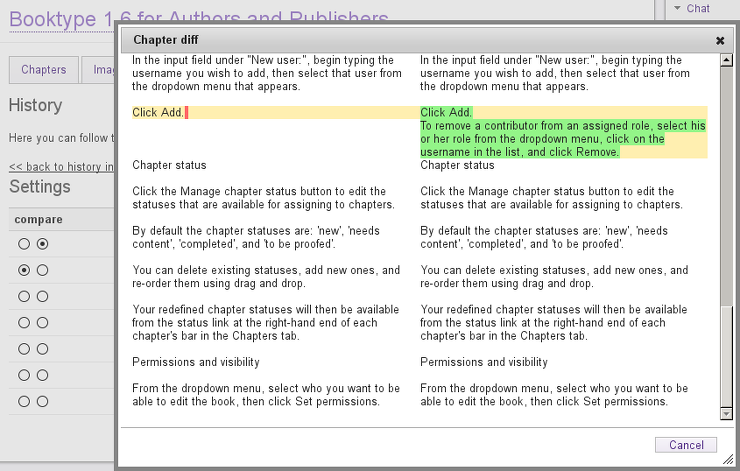

Displaying ‘diffs’ (differences) between 2 different versions of a chapter

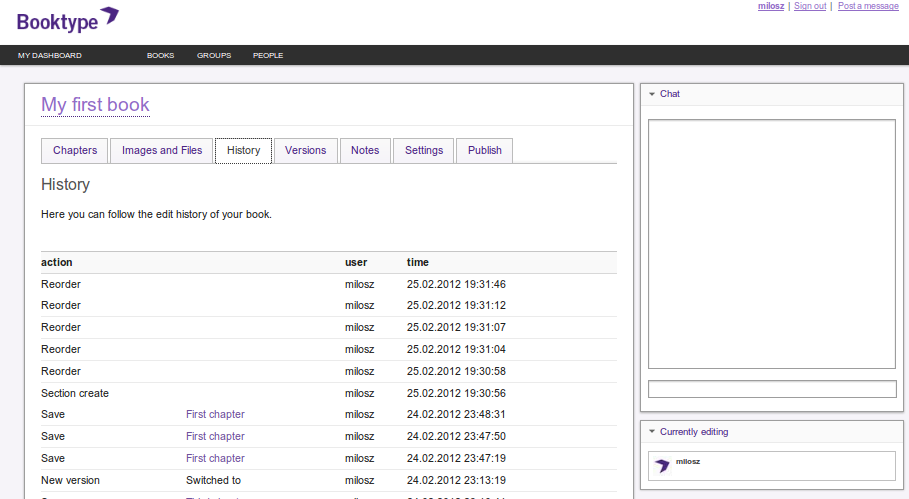

Activity stream of a book

I prototyped some interesting things in Booktype but not much of it got built. For example, I was keen on editing content in the style of the final output. The example below is using the CSS layout of Open Design Now which I mentioned below with reference to BookJS.

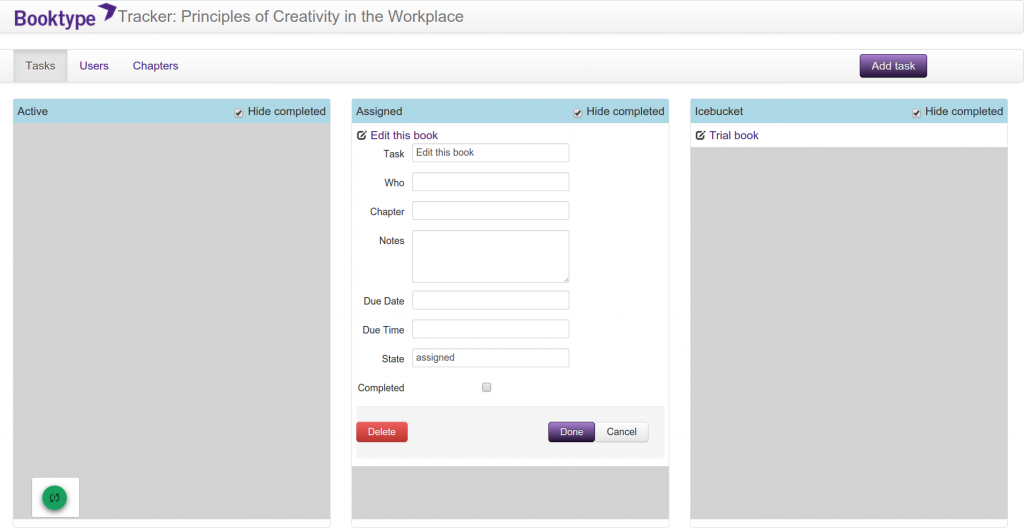

I also made a task manager prototype based on kanban cards but it was never integrated into Booktype.

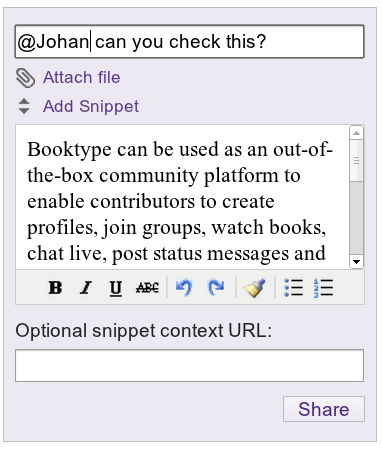

I think there are only really three parts of Booktype’s development that occurred while I was in charge of the project. First was the integration of a short messaging system into a user’s dashboard and into the editor. Essentially you could highlight text in a chapter, click on the msg widget and a short message could be sent with that text to whoever you wanted (in the system). It was intended for fact checking or editing snippets etc. The snippets were loaded into an editor to assist with this kind of use case.

A good idea but seldom used.

In addition, Booktype supported groups, so users could form groups which were populated by users and books. The idea behind this was that you could form a group to work on a collection of books collaboratively.

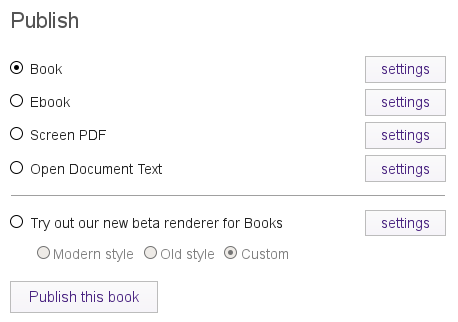

Lastly, the renderer was integrated in a more sophisticated way so you had more control of the output from within Booktype. Essentially you could choose a number of output options and style them from within Booktype.

These were all interesting additions, but in the end, Booktype was really only Booki taken a step further as a product without offering much that was new. I think we should have probably actually removed a lot of things rather than adding new things that didn’t get used.

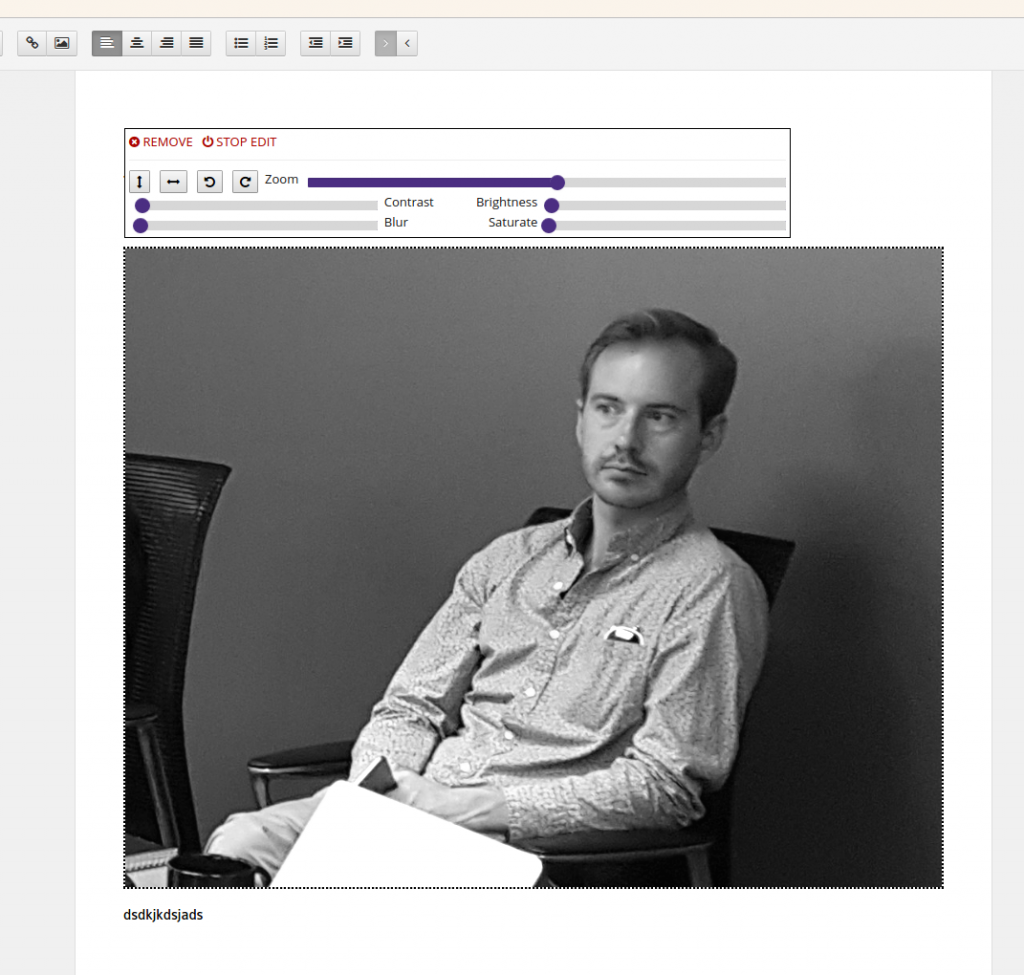

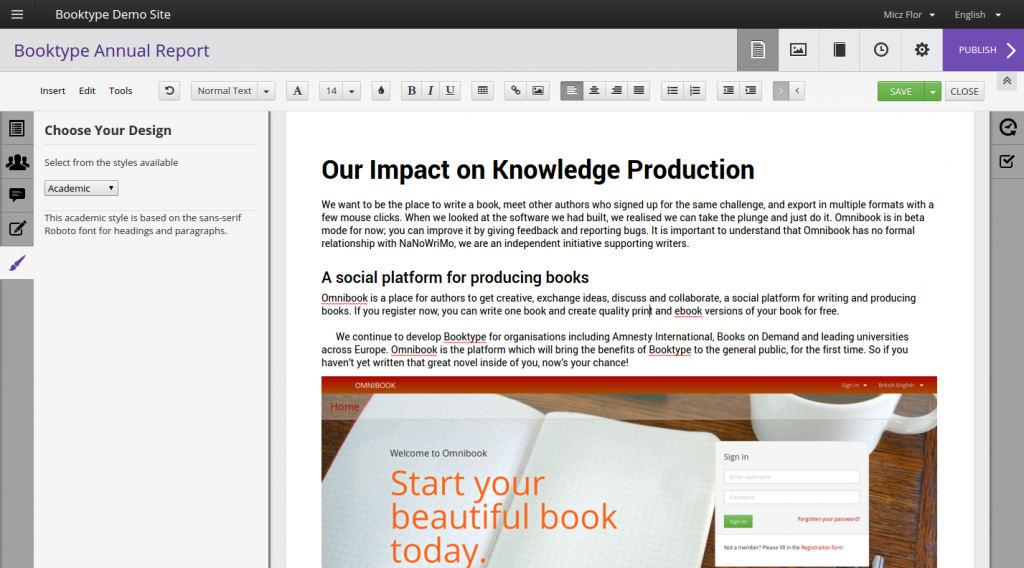

Booktype developers added some interesting stuff after I left. I particularly like the image editor and the application of themes to the content.

The image editor enables you to resize and effect an image from within the chapter editor.

The theme editor allows you to choose from an array of styles/themes and edit them.

Booktype 2 has since been released. It has become a standalone business and is doing good work. Also, the Omnibook service is a ‘booki.cc’ online service based on Booktype 2.

Booktype has been used by many organisations and individuals to produce books.

I think Booktype 2 is good software but I didn’t particularly like the direction of the Booktype UX after I left the project – it was becoming too ‘boxy’ and formal. ‘Good UX’ is not necessarily good UX. So I eventually developed another system with a much simpler approach, specifically for using with Book Sprints (but it has had other uses as well). More in this in a bit.

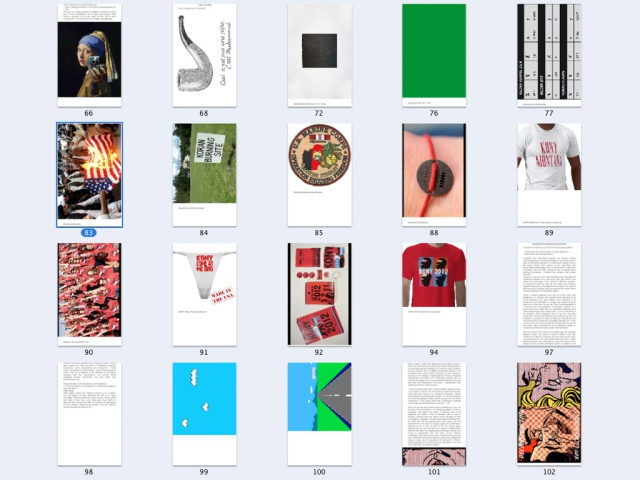

book.js

One innovation, and a further exploration of using the browser as a typesetting engine, that resulted from my time with Booktype is book.js. Essentially I had been looking for a new way to render books from HTML using the browser. I wanted to understand how Google docs could have a page in the browser and then render it to PDF with 1-to-1 accuracy. Surely the same could be done with books? However, no one could tell me how it was done. So I researched and eventually found out about the nascent CSS Regions that would allow you to flow text from one box to another in HTML. I worked with Remko Siemerink at a workshop in Amsterdam to explore PDF production from CSS. We made an interesting book with some of the Sandberg designers.

After more research and breaking down what I thought could happen, Remko worked with CSS Regions (& js) to replicate the page design of a book called “Open Design Now.” It was amazing. He got the complex design down plus it was all just HTML and CSS, it looked like a page AND when printed from the browser it retained a 1:1 co-relation. Awesome.

The following summer I was able to employ someone for Booktype to work on the tech and I hired a developer (Johannes Wilm) to work on the PDF rendering. From there we eventually had BookJS that enabled in-browser rendering of books which could then be exported to print-ready PDF by just printing from the browser. Whoot!

After time, BookJS (original site still available) could also formulate a table of contents etc. It was, and is, pretty cool and IMHO is the right way to do this. Unfortunately, Google Chrome decided to discontinue CSS Regions so if you now want to use BookJS you have to use a very old version of Google Chrome. However, better technologies have come along that support the same approach, namely Vivliostyle (which Johannes later worked on).

Github Editor

During the time with Booktype, I also did some experiments in other processes. One was using Github as the store for an EPUB and using the native zip export that Github offered to output EPUB (since EPUB is just a zip formatted in a specific way). Juan Gutierrez put together a quick demo and I published about it here:

http://toc.oreilly.com/2013/01/forking-the-book.html

Sadly the demo is no longer available but later a good buddy, Phil Schatz, adopted the idea and built something similar and (I think) much better:

http://philschatz.com/2013/06/03/github-bookeditor/

PubSweet 1

Since Booktype was going its own way, I wanted to develop a new, lighter, system for Book Sprints. Hence Juan and I worked out PubSweet, a simple PHP-based system. This would later be reformulated as a JavaScript system (see below).

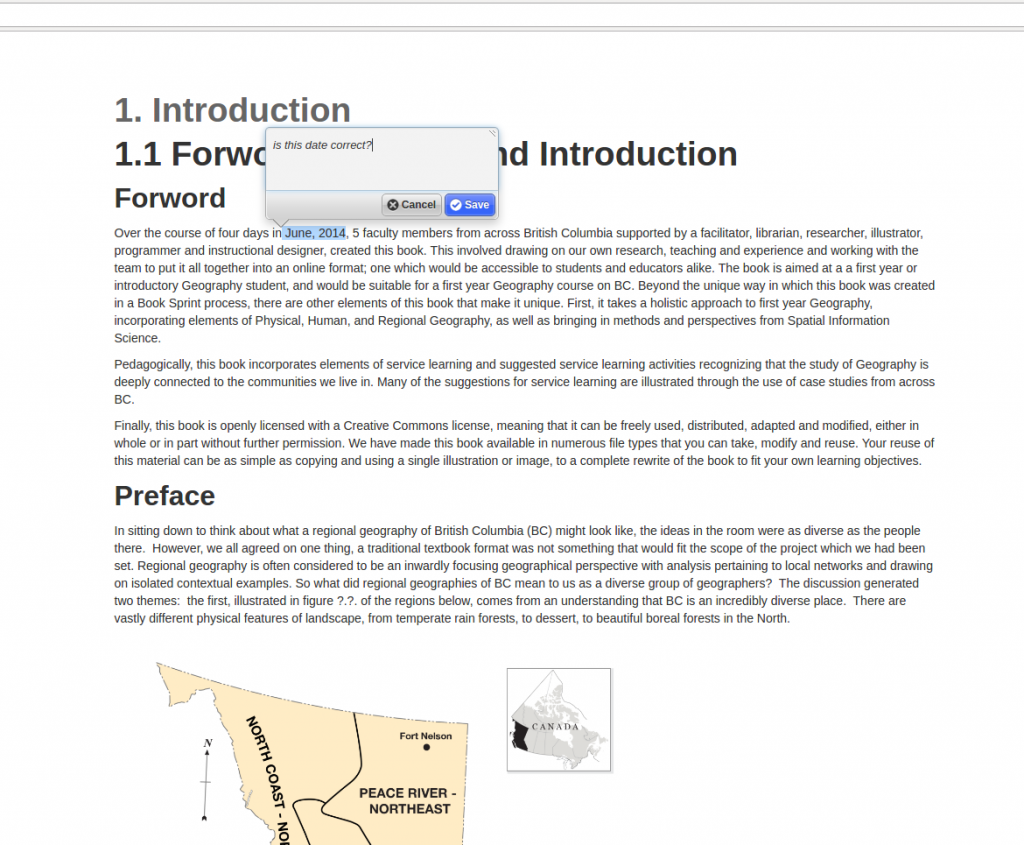

PubSweet was very simple. Essentially 3 components – a dashboard, a table of contents manager, and an editor. It would later evolve to include more features but it was really the same as the systems I had developed earlier, though simpler. I wanted to get to a cleaner interface and bare basic features. I also wanted to retain some book elements, hence the table of contents manager looks a little like a book table of contents (except the garish colors ;).

PubSweet 1 is still in use by the Book Sprints team and functions well. It uses BookJS for rendering paginated books and for PDF rendering straight out of the system. It can also generate EPUB directly. Apart from that, it is pretty simple and effective. I used a basic card-based task manager for this, based on an earlier prototype I made when working with Booktype. It was a simple kanban type board but we never properly integrated it.

We included annotation using Nick Stennings Annotator project:

PubSweet 1 has been involved in producing more books than I can count, for everyone from OReilly books to Cisco, to the World Bank, UNECA, IDEA etc etc etc

PleigOS

Somewhere along the way, I developed a simple system for creating Pleigos – one-page books created by folding a single piece of paper which has text and images. The system places text and images so that when you fold a single page after printing, a small book is formed. It was more an artistic experiment than anything but it was fun.

http://www.pliegos.net/

Note: the Pleigos project was by my good friend Enric Senabre Hidalgo, I just developed the initial Pleigos software.

Lexicon

The UNDP approached me to build software for developing a tri-lingual lexicon of electoral terminology. The languages to be supported were English, French, and regional Arabic. It sounded interesting so I used PubSweet as the basis for this.

The main difference between Lexicon and PubSweet was that you could choose to create a chapter from 2 different types of editor. Editor 1 (‘WYSI’) was a typical WYSIWYG editor. This was used for producing chapters with prose. The second type of editor (‘lexicon’) allowed you to create a list of terms, each with three different translations – English, French, and Arabic. This opened my eyes to the possibilities of having different types of editors for different content types, a strategy I hope to use again.

![]() The ‘lexicon’ editor in action

The ‘lexicon’ editor in action

The final print output looked pretty good:

![]()

The system enabled a dozen or so people from different Arabic regions to discuss translations and work collaboratively through a list while at remote locations. We built a specific discussion forum for them as part of the system and had up and down voting etc. I liked this project a lot because it was very different from any other project I had worked on yet it employed many of the same strategies.

Aperta

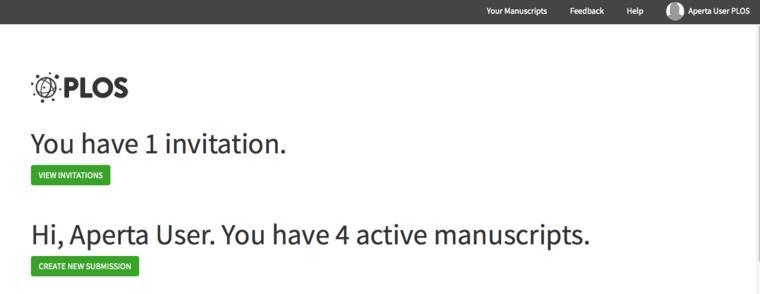

Along the way I was approached by John Chodacki of PLOS to build a Journal system for them. I knew nothing about scientific journals, so I went through a process of re-education 🙂 It sounded interesting! I spent a year-and-a-half heading up a team to design and develop this system. This is pretty much the first time I wasn’t scraping together pennies to build a system.

Journal systems aren’t that different from book production systems, in fact doing this project helped me realise that the production of knowledge, in general, follows a particular high-level conceptual schema:

- produce

- improve

- manage

- share

Each artifact (journal article, chapter, book, issue, legislation, grant application etc) follows its own kind of path, with its own unique processes, through these four stages. I have written more about this elsewhere in this blog so won’t go into more detail about it here.

Research articles, (Aperta wasn’t initially intended to deal with Journal Issues which are a collection of articles) come into a Journal as (predominantly) MS Word. They then need to follow a process of checks (eg. to make sure the article is right for the journal etc) before going through the hands of various editors (handling editors, academic editors, etc) and reviewers, including a back-and-forth with the author(s) and a final pass through a production team and/or external vendor to prep the files for publication. The biggest difference I found from my previous experience with book production systems is that there is more to-and-fro involved. Simply put, there is more workflow. So Aperta addresses this with a simple workflow engine based on the Trello/Wekan kanban card-based model.

Aperta was built in Rails with Ember JS. The front end was pretty much decoupled from the backend. It was pretty ambitious and we decided to use the Wikimedia Foundations Visual Editor at the heart of the project. It was the most sophisticated editor available at that moment. I have come to learn that you have to take what you have at the time and work with it. We committed to adopt it and make contributions. I hired the Substance.io chaps (Michael and Oliver) to work on the editor. They did a great job. (Subsequent development of their own editor libs has enabled us to work with them for Coko (more below). )

Aperta’s approach was to simplify the submission process that was managed by Aries Editorial Manager. We leveraged the OxGarage project for MSWord-to-HTML conversion and imported the manuscripts into Aperta. Then workflow templates could be set using kanban cards (as per above). These cards then enabled a flexible method for gathering information (submission data) from the authors at submission time. A lot of time was spent on getting good clean, simple, UX. The kanban card system was very modular – the cards themselves were their own applications, enabling anyone to build a card to their own requirements. This made the cards extremely powerful as they were essentially portable applications.

Further, I developed a model of sorting a lot of cards into columns much like Tweetdeck’s saved-columns model. It was all rather neat. A ton of innovation. Unfortunately, I don’t have any screenshots apart from what I see PLOS has on their website:

http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/s/aperta-user-guide-for-authors

http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/s/file?id=d45b/Aperta-Quickstart.pdf

http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/s/aperta-user-guide-for-reviewers

Aperta is in production now for PLOS Bio but unfortunately the code still isn’t available.

I think Aperta radically rethought how Journal workflows might be managed. I learned a lot through this process and it informed decisions and architecture for the next platform I was to work with – PubSweet 2, developed by Coko.

I also think taking a step into another realm where many concepts were transferable but the use case was different was very good for me. It helped me abstract a few notions. It was also good to build a sophisticated framework in another language and to have the resources to try things out. It was an excellent incubation period where I learned a lot while building a pretty good platform.

During this period I also developed a kind of Objavi 3 but I’m not sure now what it is called or if it is used.

PubSweet 2

The following systems are a result of a team of very talented people at Coko. This has been the first group of people that I have worked with that enable the systems to get close to what I believe is an ideal state for the problems at hand, the time we live in, and with the technology available. If I have learned one thing over the past years, it is that, generally speaking, development teams often prevent good solutions from happening. The Coko team is a rare case where the solutions can flourish and become what they need to be. I’m very lucky to be working with such people.

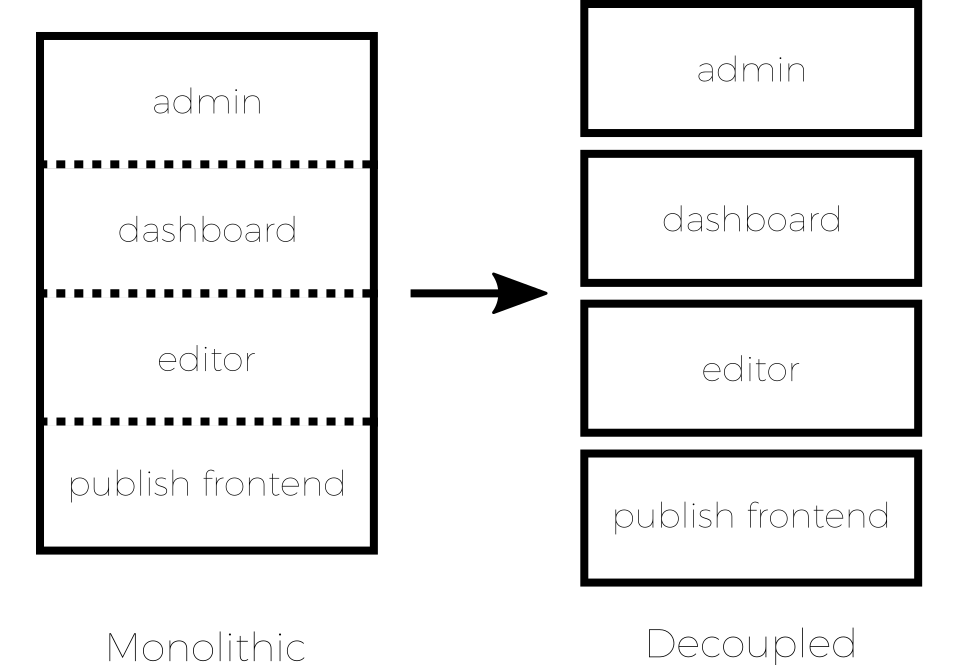

PubSweet 2 is not actually a publishing platform, it is a de-coupled JavaScript framework that enables the production of multiple publishing platforms.

With all the other platforms I have been involved with I have always learned something. So the next platform is always better. Strangely enough, because when I look back I remember, for example, thinking that Booki was the best platform ever, and perhaps the best I could do. But not so. Each subsequent platform has been much better. So… why not build a framework that enables the rapid development of many platforms at once? good idea! Imagine what you could learn… Indeed!

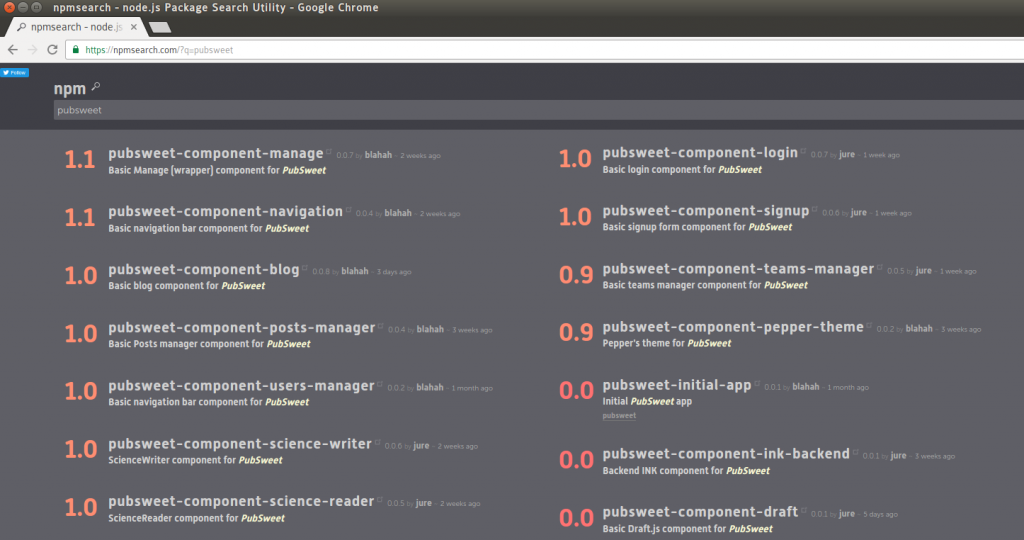

Using PubSweet, we have developed two platforms to date. Science Blogger and Editoria. For the purposes of this blog post I’ll just focus on Editoria as Science Blogger is more of a reference implementation. However, all these front components can be developed independently of each other, and independent of the core framework. Hence we have released some PubSweet NPM modules (sort of like front end plugins) online:

If you would like to read more about PubSweet check here:

http://slides.com/eset/ismte

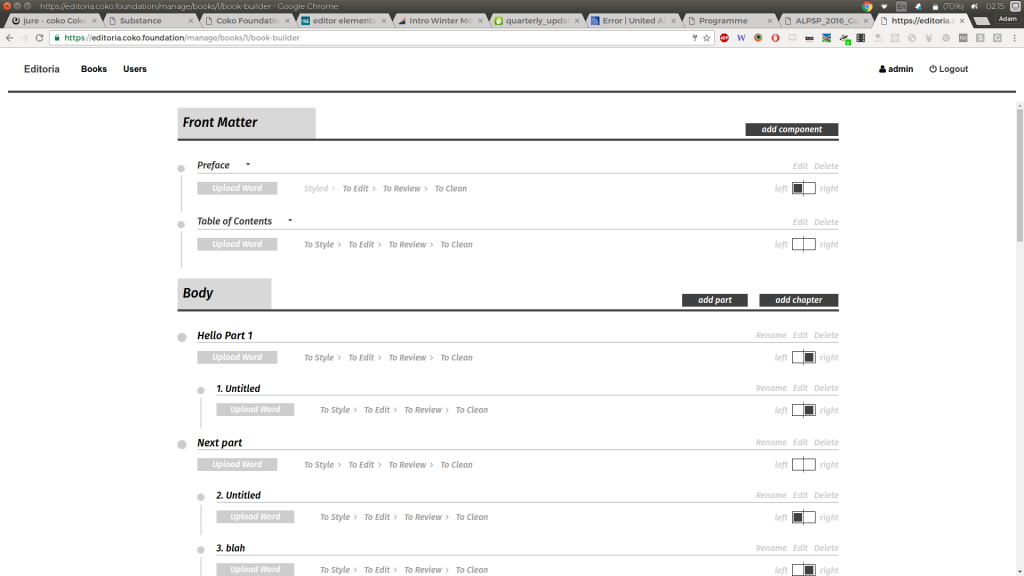

Editoria

Editoria Book Builder component

What is interesting about Editoria is that I didn’t design it. I facilitated the staff at the University of California Press to design it. And what is really interesting is that it is a better book production software than any of the above that I did design…. That’s not to say that I finally realised I was a crappy designer 😉 , rather I came to realise that given the right guidance and parameters, the people with the problems can solve the problem with more deep understanding and nuance than I could as an outsider to their processes. It was a great thing to realise.

In general, Editoria follows the same model as PubSweet 1. It is a simple collection of 3 interfaces – dashboard, book builder (in PubSweet 1 we refer to it as a table of contents manager) and a chapter editor. Very similar to PubSweet 1 and also these components fit into the conceptual schema I mentioned above of:

- produce – this happens outside the system and we convert authored MS Word files to HTML

- improve – styling, editing, reviewing, all occurs in the editor component

- manage – basic workflow managed by the Book Builder component

- share – when done we export to book formatted PDF, and EPUB

Editoria is a very simple and elegant solution. It’s the only one of the systems I have worked with that is not in production but I’m looking forward to seeing it up and running soon.

It uses the Substance.io libraries to build a custom made and elegant editor. Finally with some real $ to spend on moving this field forward, and as part of my 2015 Shuttleworth Fellowship I committed $60,000 USD (10k a month) or so to Substance, Coko followed it by a similar amount, so they could focus on the development of their libraries to 1.0. Coko also put considerable effort into founding a consortium around Substance (although I’m not convinced it is really working well yet).

http://substance.io/consortium/

Editoria brings some nice implementations to the table including the use of Vivliostyle to render PDF from HTML. Plus MSWord-to-HTML conversion, front and back matter divisions plus body content. Pagination information (left/right breaking) etc. In addition, we are building into Editoria various tools in the editor including its own annotation system and a host of publisher-specific markup options for different styles (quotes, headings etc). Coko has employed Fred Chasen for some part time work to contribute to the Vivliostyle development (although we are still working out what we should work on).

In many ways, Editoria is the system I always wanted to be involved in. It is better than any other system I have seen or been involved in and this is a result of two critical factors:

- the technologies have matured, including Vivliostyle and Substance.io, that enable critical solutions to be solved

- the people who need the system have designed it

There is more to come from Editoria, so stayed tuned…

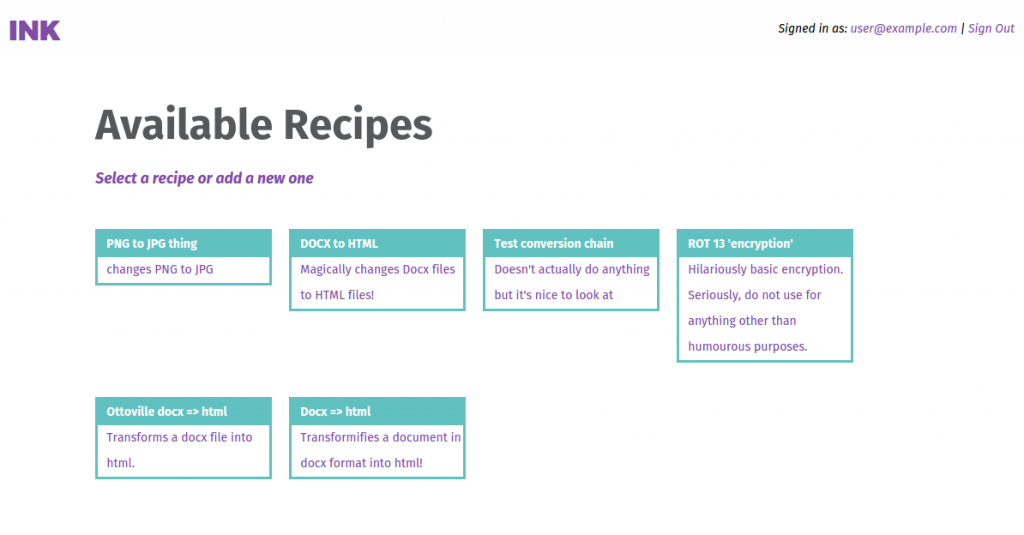

INK

INK is like Objavi on steroids. It is possibly an Objavi 4 😉 but done the right way. INK is a Rails-based web service which is primarily built to manage file conversions. However, it can actually be used for the management of any job you wish to throw at it. These jobs are what we call steps, and steps can be compiled into recipes. For example, you might have a step ‘convert MS word to HTML’ and then a second step ‘Validate HTML’. Hence INK enables you to chain together these steps.

Additionally, these steps are plugins written as Gems. A gem is a Ruby-based plugin architecture. Accordingly, you can develop gem steps and distribute them online for others to use. We hope in time there will be a free (as in beer) market around these steps.

Summary thoughts

I think I learned a lot from writing this personal ‘sense making’ piece. I didn’t realise just how strong some of the themes were that I pursued until a wrote them down…for example, I pursued collaborations from inter-organisational consortiums a number of times and none of them have worked. Huh. Interesting. I’ve also seen various practices evolve from an idea to being mature thoughts, prototypes, workable solutions and eventually, eventually, adopted. But over many more years than I expected. Also interesting.

It is also obvious that there are some big ticket technological problems that still need to be solved for good to really move forward. They are mostly there but still in need of work, the top two being:

- browser as typesetting engine

- sophisticated editor libraries

I add a third which I haven’t noted much in the above. I have worked on this since Aperta onwards and it is necessary only in the publishing world where content is authored in the legacy ‘elsewhere’ (ie MSWORD):

- reusable, sensible, MSWord to HTML conversion

This has been solved many times but has not yet been solved well.

These all need to be open source solutions. At Coko we are trying to move all these on and we are making good contributions. We, as a sector, are nearly there. Although it would be good to work more together to solve these problems by either making contributions to the existing efforts, or using their technologies. This is really the only way things move forward.

Finally, in the tech world people sometimes quote “Being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong,”. I’m not sure who said it but when I look through the evolution of technologies I have written about above, seeing various things evolve from idea to a production implementation many years later, I’m also thinking that perhaps sometimes waiting might be indistinguishable from being right 🙂