Facilitation is a key ingredient for Collaborative Design Sessions. No group should attempt this process without a facilitator. Some important things to get right going into the event include:

The facilitator is not a Benevolent Dictator

The facilitator here is not the Benevolent Dictator For Life, cat herder, or Community Manager (or other models) commonly found in open source, rather the model is closer to an unconference-style facilitator. Don’t confuse these very different approaches!

Organisational neutrality

The facilitator should not be part of the organisation that is in need of the solution. This frees the facilitator from internal politics and dynamics and enables them to read the group clearly and interact freely.

Domain Knowledge is not necessary but useful

A facilitator may be entirely neutral or, in the case where an organisation is working already with an open source product in mind, be part of the open source product development team or community. The facilitator of these sessions may or may not have domain or product knowledge. If there is no domain knowledge it is recommended product and domain experts be present. This helps a great deal to keep the process anchored to ‘product reality’.

However…there are some gotchas. If the facilitator is part of the org with ‘the solution’ (eg an open source product) then make sure someone else from your team is present. Facilitation is about trust and you can’t be both a facilitator and a product advocate. You need someone else present to advocate for the product. The second gotcha is that it is generally better for the facilitator to be neutral to all parties, however, in this case, I believe there is value in the facilitator knowing the proposed product-solution intimately (with some knowledge of how it could apply to the use case being confronted), but you will need to work extra hard to maintain your trusted neutrality (you might have to work out in advance how to manage your feelings if the group starts advocating that they don’t use your product, for example).

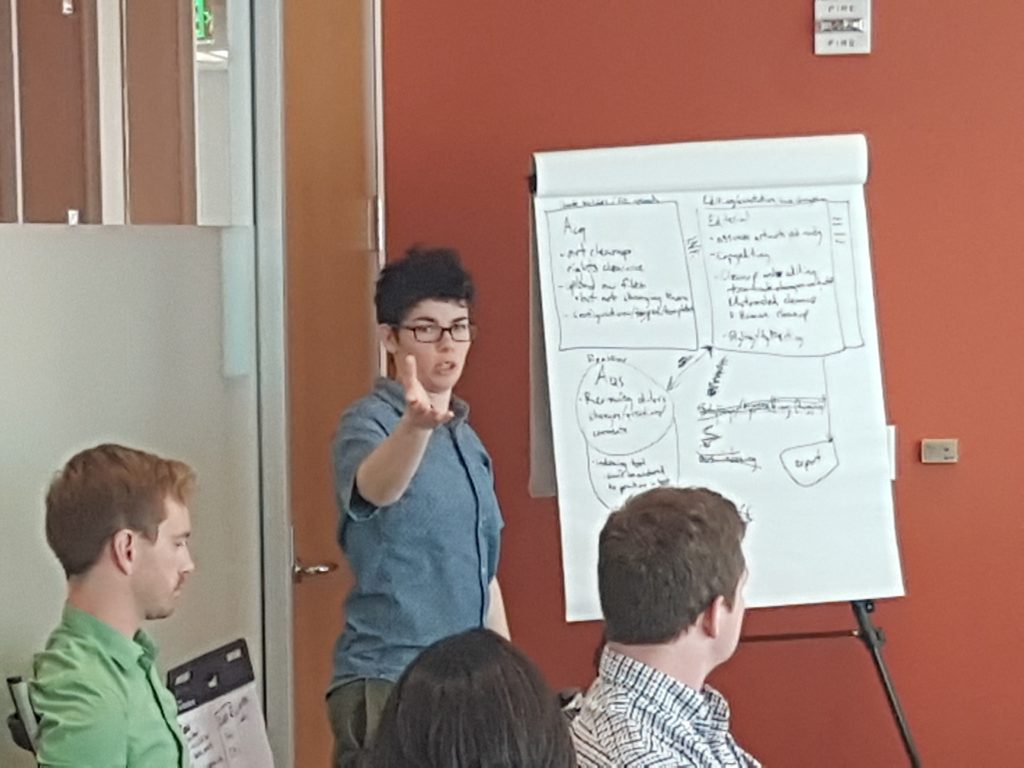

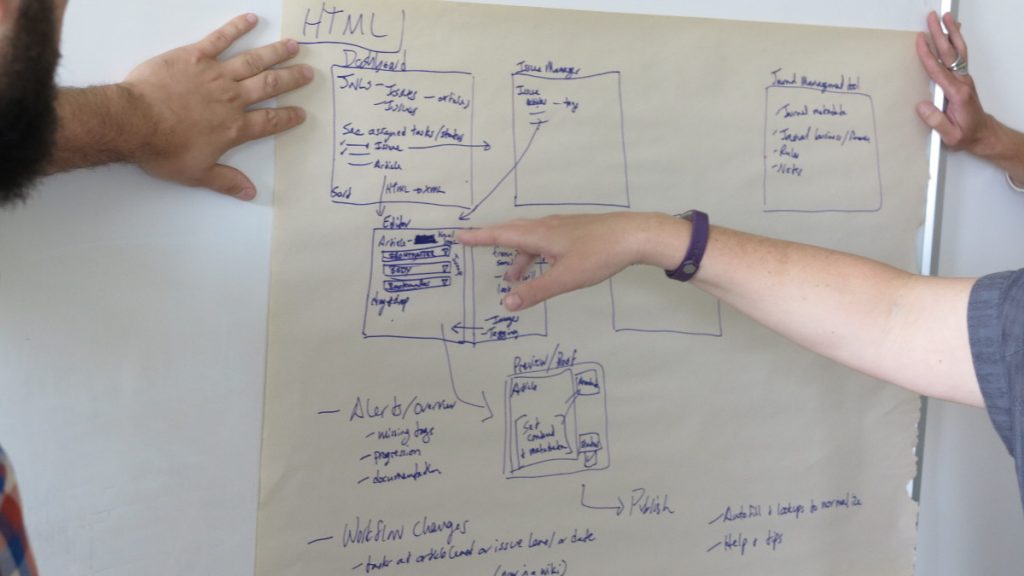

Tools

You may wish to have tools such as post-its etc, but generally, a large whiteboard and markers (or large pieces of paper) will take care of it. Most shared objects are documentation but it may be necessary at times to use other facilitation tools and tricks to move a group process along.

Facilitation Tips

Here are some things to remember when facilitating Collaborative Design Sessions:

Build trust before products

As a facilitator, your job is to build trust in you, the process, the group, and the outcomes. Each time you make a move that diminishes trust you are taking away from the process and reducing the likelihood of success. For this reason, you must put building trust, working with what people say and towards what people want, ahead of building ‘your’ product. Trust that the product and a commitment to it, will emerge from this process, and it will be better for it.

Change is cultural, not technical

Too often technology is proposed as the mechanism for change. Technology does not create change. People create change, with the assistance of technology. Make sure the group is not seeing technology as the magic wand. Change is not magically ‘embedded’ in the technology. Improvement, optimisation, or radical reworking of workflows requires people to do things differently. The group must be committed to changing what they do. The ‘what they do’ should not be posited as a function of technology, it is their behaviour that will always need to change regardless of whether there is a technology change. Behavioural and cultural change is a necessity, not something that ‘might happen’. The group needs to recognise this and be committed to changing how they work.

Focus on problems and solutions not technology

As mentioned above, cultural change is necessary and many behavioural changes can occur that will produce positive results without the need for a technology change. It is important that you and the group can identify these issues and bring them into a focused discussion. For this reason, it is very important that the initial sessions focus on what the problems are, irrespective of whether they are born of technology or workplace process. If you can accomplish this then the group may very well propose changes that have nothing to do with technology. This is a very good outcome, as the end goal is to improve how things are done. If technology change is not always (or ever) part of the solution that is also success for the process.

Even the best solutions have problems

Own that even the best solutions, including the one you are representing, will have problems. There is no perfect solution, and if there is then time will inevitably make it imperfect.

Leave your know-it-all at the door

If you are part of a product team then you may be expected to be somewhat of a domain and / or product expert. Leaving that at the door is not possible of course, but you should be careful that you do not use this knowledge as heavy handed doctrine. Instead, it should manifest itself in signposts, salient points, and inspiring examples at the right moments. These points should add to the conversation not override it. Don’t overplay your product knowledge and vision, you will lose people if you do.

Give up your solution before you enter the room

If you are part of a product team it is a mistake to enter into a Collaborative Design Session and advocate or direct the group towards your solution. If the group chooses a technology or path you do not have a stakeholding in, then that is fine. The point is, however, that the likelihood is that they will choose ‘your’ technology, otherwise, you would not be asked to be in the same room with them. However, if you facilitate the process and drive them to your solution you will be reading the group wrong and they will feel coerced. You must free yourself from this constraint and be prepared to propose, advocate, or accept a solution that is not ‘yours’ or you did not have in mind when you entered the room. This will not only free you up to drive people to the solution they want, but it will earn you trust. When they do they choose your solution, and chances are they will, then they will trust it because they trust you and trust the process. If they don’t choose it, they will trust you and come back another time when they are ready for what you have to offer and, additionally, they will advocate your skills to others.

Involve a broad set of stakeholders

The sessions should involve as diverse a range of stakeholders as possible. This will not only improve the product but increase stakeholder ownership of the solution and that in turn will help the organisation implement it. If people feel they own the solution, they will work towards seeing it implemented. Stakeholders in this context can apply to the organisation you are working with (to solve their problem) or other projects that might play a part in solving the problem. Inviting the later to the events will greatly enhance the final product and produce valuable collaborations.

Move one step at a time

Move through each step slowly. The time it takes to move through a step is the time it takes to move through a step. There is no sense in hurrying the process, this will not lead to better results or faster agreements. It will in all likelihood move towards shallow agreements that don’t stick and ill-thought out solutions that don’t properly address the problem. The time it takes to move through a step will also give you a good indication of the time needed for the steps yet to come. Be prepared to re-scale your timelines at any time and to return to earlier unresolved issues if need be.

Ask many questions, get clarifying answers, ask dumb questions, the dumber the better

Ask many many questions. Try not to make them leading (note: sometimes leading questions are necessary for points of clarification or illustrating an issue). Keep asking questions until you get clear simple answers. Breakdown compound answers where necessary into fragments and drill down until you have the clarity you need. Dumb questions are often the most valuable. Asking a dumb question often unpacks important issues or reveals hidden and unchallenged assumptions. It is very surprising how fundamental some of these assumptions can be, so be brave on this point. If necessary feign humbleness and stupidity for asking an obvious question.

Own stupid problems, laugh about them!

Every workplace culture knows they do some stupid things. When you find these, call them out, and, if possible, laugh about them. Providing a context where people can bring forward and own ‘stupid’ processes in an easy way is going to help identify the problems and move towards solving them. It also sometimes gives people an opportunity to question things that they never felt made sense and this may, in turn, help others question the ways things are done – this is very valuable and is not always possible in the everyday workplace environment. Bringing these issues out can be very revealing, it gets people on the same page, and is often cathartic.

Reduce, reduce, reduce

The strongest point is a simple one.

Get agreements as you go

Double check that everyone is on the same page as you go. Get explicit agreement even on seemingly obvious agreements. Total consensus is not always necessary but general agreement is.

Document it all

Get it down in simple terms on whiteboards or whatever you have available. At the end of sessions commit this to digital, shareable, media.

Summarise your journey and where you are now

At the end of a session, it is always necessary to summarise in clear terms the journey you have taken and where you have arrived. Get consensus on this. It is also useful at various points throughout the session to do this as a way of illustrating you are all on the same journey and reminding people what this is all about. When doing this it is very useful to make points in this summary that illustrate that you understand them – bring out points that may have taken a while to get clarity on or that you may have initially misunderstood (there will be many of them if you are doing your job well!) so the group knows that you are embedded with them and not merely massaging them towards your own pre-designed end game.

State your willingness to discard your own product

Nothing builds trust more than statements to show that you are invested in helping them achieve what they need over what you want. Your investment in this, as with all your actions and statements, must be genuine. For this reason, too, you should accept conclusions that propose cultural solutions over technical, and other people’s products over yours. This also implies you need some fair understanding of products competitive in your space and you should not make denigrating comments about them, but instead recognise when they have value. The assumption is however that since they invited you here, and if you are doing a good job, people will choose your product anyway – but you must let them make that choice. It’s OK to highlight this dilemma and probably helps things if you do and do so in a light-hearted way.

All solutions must be implemented incrementally

Do not design and then build the final solution all at once. Solutions must be deployed incrementally and learnings folded back into the proposed solution. Build to a minimum proposition, try it, learn, redesign, repeat.

Bring in the competition

During CDS it is sometimes a good idea to have complementary or competing technology providers at the session. You will probably find that his leads to great collaborations, each contributing what they excel at.

Use their semantics

Use terminology to describe the problem and solution that come from the group. Don’t impose your own semantics.

Facilitation is an art of invention

While this section has not been about how to facilitate it is important to make a note about invention before the next section in the hope that no one just reads the below as an instruction manual. There are processes and methods that you can use ‘off the shelf’ as a facilitator but none of them will translate from paper to reality in a one-to-one mapping. People are too weird and contexts too variable to ever allow facilitators the luxury to do it by numbers. At the very least facilitation is an act of translating known patterns into a new context and tweaking it to fit. But the reality is that much of the what a facilitator does is to make things up. Instinct and the fear of failure force on-the-fly invention of methods, but each time a good facilitator makes it appear that the method has existed for a hundred years and never been known to fail. When it does fail, a really good facilitator will ensure no one notices and that the outcomes were the typical, expected, ones you were after.