The new Collaborative Knowledge Foundation website is now live. It was designed by the fabulous Dutch design company the van Leeuwen Brothers. I have known designer Henrik van Leeuwen for many years. He’s a good friend, talented designer, and great artist. Henrik has done all the illustrations for Book Sprint books for many years now and does almost all the Book Sprint cover designs. He developed the Book Sprint and Coko logos and now the Coko website. Henrik and his brother Kresten are huge talents and if you are looking around for good designers I highly recommend them.

Tag: Book Sprints

The first not-really Book Sprint

I have been poking around in my own archives recently. It’s pretty cool to remember things that I had completely forgotten. Anyway, the following is a post I found about the first Book Sprint. It was about Pure Data and held on the little island of Korčula, Croatia. A buddy, Darko Fritz, let us use his apartment in the center of the old town. I was to join two friends, Derek Holzer and Luka Prinčič, at the apartment for 3-ish days. However, on the way I had a health freak out and had to participate remotely. It was our first attempt at a Book Sprint and looks almost nothing like how Book Sprints are done now, but it was a starting point and gave me a lot to think about.

The following is the report written by Luka for the FLOSS Manuals site. I love the two images in the post. They are the only images Luka and Derek sent me of this mysterious event.

So, Adam sent us (he was supposed to come too, but couldn't at the end) - he sent Derek Holzer and myself to this Croatian island Korcula, into the little (but very very cute) town named the same (Korcula) so that we Sprint-it up and write a Pure Data manual for FLOSS Manuals. I took my little old red car and drove down from Ljubljana over Rijeka and under scary stoney Velebit entering the warm sunny region of Dalmatia and driving further towards Split. Now this was a fun ride, especially under Velebit was very scenic. My cup of tea, as I hate the boredom of motorways. And my clutch was going to hell too, so my fingers were crossed. In split I caught this superfast catamaran-pedestrian-ferry that took me in under three hours to Korcula where Derek was waiting for me. And for phone line. And for internet connection.In this lovely little town with incredible feel of Venetian architecture, tiny little streets, all set in stone, we waited for ADSLine to appear, which it did right next morning. The evening before we discussed over a plate of Italian pasta and a beer what would be good to work on in the coming days. After the internet magically appeared (yeah right!) we could also discuss with Adam, who was in Amsterdam, over Skype how to work and what to work on. Derek was somewhat the main captain although each of us worked on our own chapter. Adam was going after installation instructions for various platforms, Derek was rewriting and expanding tutorial on how to build a simple synth, and I was going deep into 'Dataflow' tutorials.

On Monday when I arrived, the sea was quite wild as there was a lot of wind. Tuesday was all gray and rainy. We had some talk about doing some hiking, as Derek had already explored some terrain, but Tuesday was a bit too wet, so we stayed in and worked on bits and pieces trying to see how much work there is and how writing feels. It seems from the after-perspective that this was the day to slowly get the grip on how the writing will go. On Wednesday, we took a bus in the morning to a nearby village by the coast and with a little map from the tourist office tried to find that little path that would correspond to a tiny dashed black line that goes up the hill towards another village about 500m higher. We searched for more than an hour until finally a communicative small but wide man told us that old paths were overridden with a new tarmacced road. "I used to go up those little paths, when I was young..." he said, "but now there's a road so why would one bother, but if you really want there's a little path there, you can find it...." We walked a path for a while and than decended slightly to find a road and walked the road for an hour, maybe two, under not-too-hot spring-ish sun. It was lovely. After icecream in a local shop (those local shops are always something!) we caught a bus and went back 'home'. We started to work immediately, had some lunch and worked quite late into the night. We talked to Adam over Skype and kept working each on our own part. Interestingly, and maybe because we were supposed to leave on Saturday morning (Derek had a plane ticket), next two days somewhat turned into a bit of frenzied work. As we knew we had just two days left, we tried to finish our parts. In consequence, at the end of Friday, we realized we hadn't gone out much. A real Sprint! One of us would go to the shop now and then, couple of times a day, and cook something (mostly pasta! - but I found some local home-made from Istria, and also Korcula olive oil!) The weather was nice, not cold, with many bits of sun. The voices of kids, sometimes horny cats, and other inhabitants were protruding through an open door and were making a special kind of atmosphere. It was lovely to feel this Venetian-medieval town around you. Our flat was on the third, top floor, we could see the sea from it and the roofs around us. On the friday evening we found ourselves with two huge finished chapters, both quite satisfied with it. We were tired but happy we made something. We searched the town for fish and found an empty but slick-looking restaurant with a young owner-cook who made us some fish and vegetables. I guess we could have made them ourselves at home, but none of us spotted a fishery and had much time and energy left. I must say it has also been very educational for me to listen to Derek's peculiar playlist which included a lot of metal, old rock (Black Sabbath, etc) and African (Angolan) music from 70s. Luckily, Derek had a near perfect (or at least compatible) feel for sound levels, so it was always very enjoyable to become aquanted with a genre I haven't explored yet in my life much. In the aftermath of the Sprint of two-and-a-half days, we both felt we wouldn't be able to go like this for another day. If anything, we would need a day, or ideally two days of real break from this and than we could come back to the book with passion. I was thinking this would be great to do three or four times. In waves. Either that, or steadily work for 8, maybe 10 hours per day and then have a break. But I think this also depends on the writer and her/his ability and fitness to write. At the last moment I decided to stay for another two days (as our 'landlord' told us we could stay for us long as we liked, and Adam agreed). So Derek left on Saturday morning (6 am, ugh) and I worked on some of my music and had couple of walks around town and surroundings, really enjoying it immensely. My car was still where I left it in Split, and the clutch was still functioning (barely), so I drove back, under lovely Velebit of course. It was almost like summer all the way to the border with Slovenia, where heavy rain was waiting for me.

Korčula image by PJL (Own work) CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)

The Old Days

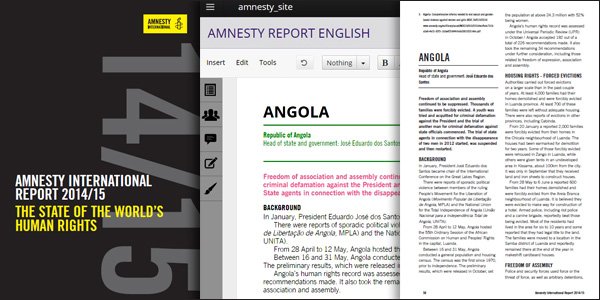

Wow…I was browsing some old archives to update this new version of my site. I found the most incredible stuff in the Internet Archives Wayback Machine including the outline of a description of Booki (2010) many years before it became Booktype. Amazing! I didn’t think I had the product manager in me but it seems once upon a time I was really focused on this kind of acute detail for product management. I had forgotten!

Forgive the long post, it’s just pure indulgent nostalgia for me. In any case, here is one of the emails I found really fascinating, from back in 2010, talking about features for Booki and Objavi (book renderer). This has been taken from the zip of a public list we used for dev at the time:

https://web.archive.org/web/20111029143503/http://lists.flossmanuals.net/pipermail/booki-dev-flossmanuals.net/

I’m so astonished how much of my thinking recorded in this email carries through to the way we are approaching product development for Coko now. The statement:

You might have noticed that I prefer to take the easy road for features, leaving as much open as possible, and then refine according to use. That is because,from experience, I have learned that when designing software it is better to be led by the user rather than force them into an imagined work flow.

Might as well be out of the Collaborative Product Design manifesto.

I’ts kind of incredible. The email documents so much of how we were thinking at the time, including using HTML and CSS to create paginated books using browser engines:

* Objavi utilises Webkit for PDF generation. Later Gecko will be added.

…and later in the product description…

3.2.2 CSS Book Design Status: High Priority, Implemented Function: The default PDF rendering engine for Booki is now Webkit and will eventually be Mozilla Firefox hence there is full CSS support for creating book formatted PDF in Booki. This changes the language of design from Indesign to CSS - which means any web native can control the design of the book.

Pretty interesting, if only to me! Anyway, the email is below, it documents some features we built on commission for Source Fabric before they eventually took over the project. Thank you for indulging me 🙂

From adam at flossmanuals.net Wed Jul 28 09:11:21 2010

From: adam at flossmanuals.net (adam hyde)

Date: Wed, 28 Jul 2010 18:11:21 +0200

Subject: [Booki-dev] notes to meeting

Message-ID: <1280333481.1582.143.camel@esetera>

hi Frank,

It was good to meet you and I'm glad Source Fabric is considering working with us and you to develop features they and we need (Aco is also keen for this).

I have sent this email to the dev list and to you and Micz. It might be good for you both to consider joining the list.

http://lists.flossmanuals.net/listinfo.cgi/booki-dev-flossmanuals.net

Below the content of this email is a very basic requirements doc. It does not outline the notes tab, so I thought I would make some notes here for your (and Micz's) consideration should Source Fabric decide they wish to commission all or part of this development.

In essence, I think that the notes tab could nest the following:

1. To do list

2. Book notes

3. Style guide

These could be hidden via a dropdown or accordian style interface. Our plan is to keep everything as simple as possible so I would imagine a page with three headings and clicking on each reveals the information behind it.

Some ideas:

1. To do list

The basic form could be a Jquery to do as we looked at today:

http://demo.tutorialzine.com/2010/03/ajax-todo-list-jquery-php-mysql-css/demo.php

If this is the format, it would be good enough as it is. The good news is that this is done using Jquery so I imagine this is a very easy implementation. What you would need to work out, however, is how Aco implements the dynamic updates so that when a to do is altered everyone has that info updated.

If there was room to take this development a step further, I would recommend considering adding the following fields:

* assigned to

* due date

* priority

I am not married to those ideas though as I think we need to insure that the interface does not have too many things going on. So I would actually recommend we start with the basic implementation and move on. When users have tried it then we can consider extending it with these items.

2. Book Notes

Something like etherpad would be good but too complex (see.

http://piratepad.net/ )

I would suggest considering either a) the same interface as we have now in the notes pad except with a very very simple WYSIWYG or b) a threaded comment system. I think the best would again be to do the easiest and simplest - what we have now with a WYSIWYG interface (and no need to press 'save'). Then when users use it we extend according to demand for most-needed features.

3. Style Guide

This is pretty much the same as (2) except it would be used for storing the Style Guide. A style guide is optional but many people request it in FLOSS Manuals and some go out of their way to create one so I think this would be a very good feature to anticipate based on our user experience so far.

I think all of the 3 above are simple and I think Source Fabric's working process (especially for the forthcoming Sprints) would benefit a lot from them.

You might have noticed that I prefer to take the easy road for features, leaving as much open as possible, and then refine according to use. That is because from experience I have learned that when designing software it is better to be led by the user rather than force them into an imagined workflow.

It has worked well for us so far - everything you now see in Booki is pretty much that way because we have tried similar ideas in FLOSS Manuals and seen their effect. I would prefer to continue to work this way with Booki.

So...there was one more feature we discussed - Chapter Level notes. I think this would be extremely useful for Source Fabric (but Micz needs to comment on this) but we need to be careful that we get it right because it is not so obvious how this might work.

I think the notes have to be associated with the chapter page when you edit it - however there is very little space there. One possibility is to build this into the WYSIWYG editor - Xinha - as a 'notes server' or some such. ie. it opens from the WYSIWYG editor but stores the content (chapter notes) in the booki db. The risk here is that people will not know that the notes are there...so we need to consider this. Another possibility is to build this into a 'sliding tab' as Micz suggested. I think that might be ok but it would have to be done carefully as it might look too much like a gimmick.

The other issue with chapter level notes is that I strongly believe that an overview of all chapter notes for a book should be able to be seen somewhere, in one place. Otherwise it would mean checking each chapter which would be a tedious job (books easily have 30+ chapters). So if you consider Chapter notes then you must also consider how to do this.

So on this I am not so clear what would work well for Chapter level notes and because of this I think it's not such a good feature for our first adventure working together. I would recommend instead the first three to be done all together - however this is up to Micz.

My feeling is that the first 3 are an extremely quick development, first however you need to know how it all fits together so i would suggest emailing this list when you have questions and I am sure Aco will answer your questions...

Also, Aco is currently working on the Booki site update so I expect the GIT repo is not updated but will be within the next days once the booki www is updated....

also you should meet Doug - doug is on this list and he is the Objavi (PDF generator) developer....doug - frank, frank - doug

also, meet John who does the Booki manual and other essential tasks intro intro :)

:)

adam

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Description

Booki is designed to help you produce books, either by yourself or collaboratively. A book in this context is a "comprehensive text" which can be output to book-formatted PDF (for book production), epub, odt, screen readable PDF, templated HTML and other formats.

Booki supports the rapid development of content. Booki has tools to support the development of content in 'Book Sprints'. Book Sprints are intensive collaborative events where collaborators in real and remote space focus on writing a book together in 3-5 days.

While you can use Booki to support very traditional book production processes, the feature set matches the rapid pace of publishing possible in the era of print on demand and electronic readers. Booki can output content immediately to multiple electronic formats. Print ready source (book formatted PDF) can be immediately generated, and then uploaded to your favorite Print on Demand (PoD) service, taken to a local printer, or delivered to a publisher.

1.2 Purpose

Booki embraces social and collaborative networked environments as the new production spaces for comprehensive (book) content.

1.3 Scope

Booki is available online as a networked service (http://www.booki.cc) for free. This service is a production tool for the creation of free content and not a publishing/hosting service. Content produced within Booki.cc is intended to be published elsewhere, either under another domain, in paper form (ie. books), distributed in electronic formats, or re-used in other content.

Booki can be installed by anyone wishing to utilise this software under their own domain or within private or local networks.

2 OVERALL DESCRIPTION

2.1 Product Perspective

Booki takes what was learned from building the FLOSS Manuals tool set and posits these lessons within a more suitable architecture.

Booki is the name of the collaborative production environment, however there are 2 associated softwares that provide all the services required :

Booki - production environment

Objavi - import and export engine

This document refers to Booki 1.5 and Objavi 2.2

2.2 Booki Functions

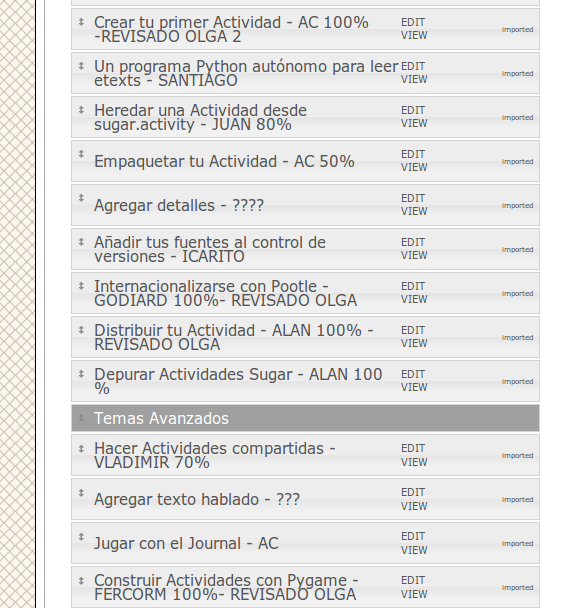

* User account creation requiring minimal information

* One click book creation

* Drag and drop Table of Contents creation

* One click editing of chapters

* Chapter level locks

* Live chat on a book and group level

* Live book status reports (editing, saving, chapter creation) delivered

to the chat window

* Drop down chapter status markers

* One click to join a group

* One click to add a book to a group

* One click exporting to epub, screen pdf, book formatted pdf, odt, html with default templates

* Easily accessible advanced styling options for export (CSS controlled)

* User profile control (status, image, bio)

* One click group creation

* Easy importing of book content from Archive.org, Mediawiki, other Booki installations

* Option to upload content to Archive.org

2.3 User Characteristics

2.3.1 Contributor

The majority of users will be contributors to an existing project. They may contribute to one or more project and may produce text and/or images, provide feedback or encouragement, proof, spell check, or edit content. These are the primary users and the tool set should first meet their needs.

2.3.2 Maintainer

These are advanced users that create their own books or have been elevated to maintainer status for a book by group admins. Maintainers have associated administrative tools for the books they maintain which are not available to other users.

2.3.3 Group admin

These are advanced users that wish to establish and administrate their own group. They have maintenance tools for every book in their group plus additional group admin tools.

2.4 Operating Environment

Booki is designed primarily for standards-based Open Source browser comparability but is tested against other browsers.

2.5 General Constraints

* Booki and Objavi are Python-based.

* Booki is built with the (bare) Django framework.

* Booki uses Jquery for dynamic user interface elements.

* Booki uses Postgres as the database but sqlite3 can also be used

* Redis is used by Booki for persistent data storage to mediate dynamic data delivery to the user interface

* Objavi utilises Webkit for PDF generation. Later Gecko will be added.

* Rendering of .odt by Objavi requires OpenOffice to be installed with unoconv.

* The Booki Web/IRC gateway may eventually (and optionally) require a dedicated standalone IRC service hosted on domain.

* Content editing in Booki is done by default with the Xinha WYSIWYG editor

* XHTML is the file format for content.

* Content will be ultimately be stored in GIT.

* Localisation in Booki is managed with Portable Object files (.po).

* The code repository for both projects is GIT with a dedicated Trac for bug reporting and milestone tracking :

http://booki-dev.flossmanuals.net

* A Dev mailing list is maintained here:

http://lists.flossmanuals.net/listinfo.cgi/booki-dev-flossmanuals.net

* Developers can be reached in IRC (freenode, #flossmanuals)

* Each release will be as source. Beta and later releases will also be available as Debian .deb packages.

* User and API Documentation will be maintained in the FLOSS Manuals

Booki Group.

* For development we use Apache2 for http delivery

* The license is GPL2+ for all softwares

2.5 User Documentation

Maintained here : http://www.booki.cc/booki-user-guide/

3 SYSTEM FEATURES

3.1 Booki Features

3.1.1 Booki-zip (Internal File Format)

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: A Booki-specific file structure for describing books

Interface: Used for internal data exchange between Booki and Objavi.

Notes: booki-zip definition maintained here :

http://booki-dev.flossmanuals.net/git?p=objavi2.git;a=blob_plain;f=htdocs/booki-zip-standard.txt

3.1.2 Account Creation

Status: High Priority, Partially Implemented

Function: Quick access to a registration form from the front page for account creation

Interface: Requires only username, password, email and real name (required for attribution). Email is sent to the user with autogenerated link for verification

Notes: email confirmation mechanism missing

3.1.3 Sign in

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Quick access to a sign-in form from the front page

Interface: Username and Password form and submit button. Username and

pass remembered.

3.1.4 Profile Control

Status: Medium Priority, Implemented

Function: When logged in the user can access a profile settings page to set personal details (email, name, bio, image). Personal details can be browsed by other users

Interface: "My Settings" link in user-specific menu on left gives access to a form for changing the details.

3.1.5 Book Creation

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Users can create a book from their homepage ("My Profile").

Interface: User can click on "My Profile" link from the user-specific menu on the left. On the Profile page a text field for the name of the book, and a license drop down menu (license *must* be set) is presented.

Clicking on "Create" adds the empty book with edit button to the listing of the users books on the same page.

3.1.6 Archive.org Book Import

Status: Medium Priority, Implemented

Function: Users can import books from Archive.org

Interface: "My Books" link in the user-specific menu on the left presents the user with a field for inputting the ID of any book from

Archive.org. The book is then imported when the user clicks "Import".

Notes : Interface is through Booki but Objavi does the importing and returns Booki zip to Booki. Relies on Archive.org successfully delivering epub for each book but this is not always happening. Needs error catching and user friendly progress/error messages.

3.1.7 Wikibooks Book Import

Status: Medium Priority, Implemented

Function: Users can import books from Wikibooks

(http://en.wikibooks.org)

Interface: "My Books" link in the user-specific menu on the left presents the user with a field for inputting the URL of any book from Wikibooks. The book is then imported when the user clicks "Import".

Notes : Interface is through Booki but Objavi does the importing and returns Booki zip to Booki. Needs thorough testing as it is sometimes failing possibly due to time-outs. Needs error catching and user friendly progress/error messages. Should be extended to be a "mediawiki import" tool, not just for Wikibooks.

3.1.8 Epub Book Import

Status: Medium Priority, Implemented

Function: Users can import any epub available online

Interface: "My Books" link in the user-specific menu on the left presents the user with a field for inputting the URL of any epub. The book is then imported when the user clicks "Import".

Notes : Interface is through Booki but Objavi does the importing and returns Booki zip to Booki. Needs thorough testing as it is sometimes failing possibly due to time-outs. Needs error catching and user friendly progress/error messages.

3.1.9 Group Creation

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Users can create groups.

Interface: "My Groups" link in the user-specific menu on the left presents user with 2 text fields - group name, and description. When a name for a group is entered and "Create" is clicked then the group is created.

Notes: Group admin features missing.

3.1.10 Joining Groups

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Users can join groups with one click.

Interface: "Groups" link in the general menu on the left presents a list of all Groups, by clicking on link the user is transported to the homepage for that group. At the bottom of the page the user can click "Join this group" and they are subscribed.

3.1.11 Adding Books to Groups

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Users can add their own books to groups they belong to.

Interface: While on a Group page that the user is subscribed to the user can add their own books to the group.

Notes: When Group Admin features are in place we will change this so that Group Admins set who can and cannot add books to groups. At present a book can only belong to one group.

3.1.12 Readable Book Display

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Users can read stable content in Booki without the need to log-in.

Interface: Upon clicking on the "Books" link in the general menu on the left a page listing all books is presented. Clicking on any of these presents a basic readable version of the stable content. Alternatively users can link to a book on the url http://[booki install domain]/[book name]

3.1.13 Edit Page

Status: High Priority, Implemented

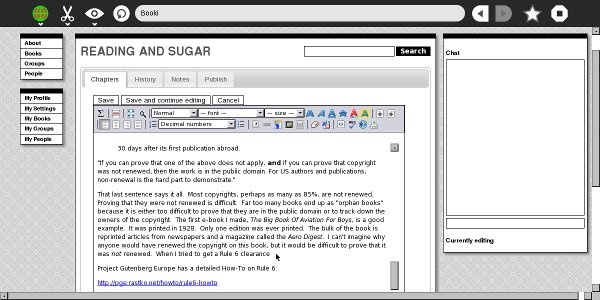

Function: Page for editing content.

Interface: The edit page is accessed by clicking on "edit" next to the name of a book in "My Books" or "Books" (all books) listings. The user is then presented with a page with tabs for : editing, notes, exporting, history

3.1.14 Edit Tab

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Edit interface for chapters.

Interface: Clicking ?edit? on a chapter title will open the Xinha WYSIWYG editor with the content in place.

3.1.15 Notes Tab

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: A place for contributors to keep notes on the development of the book

Interface: User clicks on the Notes tab for a book and is presented with a shared notepad for recording issues or discussing the development.

Notes : Implemented but future direction TBD

3.1.16 History Tab

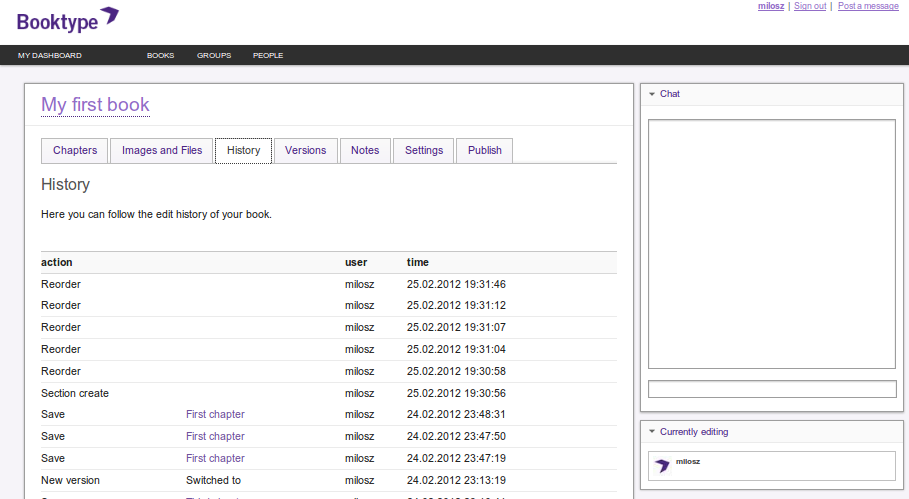

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Shows edit history of the book

Interface: User clicks on the history tab and can see the edit history with edit notes.

Notes: Implemented but unreadable. Users should also be able to access diffs here.

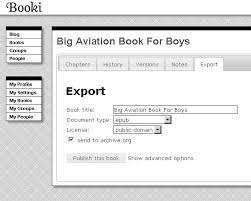

3.1.17 Export Tab

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Export content to various formats

Interface: User clicks on the Export tab and is presented with a form for choosing export options. Clicking "Export" returns the desired output for download.

3.1.18 Version Tab

Status: High priority, Not Implemented

Function: can easily freeze content at stable stages while work continues on the unstable version.

Interface: From the Edit Page a maintainer sees an extra tab "Version".

>From here a maintainer can click "create stable version" - the last stable version is archived recorded and the current version becomes the new stable version.

3.1.19 Subscribe to edit notifications

Status: High Priority, Not Implemented

Function: Users can subscribe to edit notifications

Interface: User clicks "Subscribe to edit notifications" from the Edit Page for a book. If there are edits made a synopsis is emailed with basic edit information (time, chapter, person who made the change, version numbers) and a link to the diff.

3.1.20 Chat

Status: High priority, Implemented

Function: A real time chat (web / IRC gateway).

Interface: Persistent on the edit page for any book.

3.1.21 Localisation

Status: High priority, Not Implemented

Function: Booki needs to be available in any language where it is needed. Hence we may integrate the Pootle code base into Booki to enable localisation of the environment.

Interface: TBD

3.1.22 Translation

Status: High priority, Not Implemented

Function: Content can be forked and marked for translation. A

translation version of a book will provide link backs to the original

material, be placed in a translation work flow, and edited in a

side-by-side view where the translator can also see the original

source.

Interface: TBD

3.1.23 Copyright Tracking (Attribution)

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Any user contributions are recorded and attributed.

Interface: All attributions are automated in Booki. Book level attribution is output in any chapter that contains the string "##AUTHORS##"

Note: should be a syntax for producing Attribution notes on a per-chapter basis eg. "##CHAPTER-AUTHORS##"

3.2 Objavi Features

3.2.1 Book-Formatted PDF Output

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: the server side creation of Book Formatted PDF is a pivotal feature. This is managed by Objavi which runs as a separate service. The book formatted PDF supports Unicode, bi-directional text, and reverse binding for printing right-to-left texts on a left-to-right press and vice versa. The formatting engine outputs customisable sizes including split column PDF suitable for printing on large scale newsprint.

Interface: This feature is managed by Objavi, an API is functional and feature rich but not well documented at present. Objavi also presents a web interface for those wanting more nuanced control (see http://objavi.flossmanuals.net/).

3.2.2 CSS Book Design

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: The default PDF rendering engine for Booki is now Webkit and will eventually be Mozilla Firefox hence there is full CSS support for creating book-formatted PDF in Booki. This changes the language of design from Indesign to CSS - which means any web native can control the design of the book.

3.2.3 Export Formats

Status: High Priority, Implemented

Function: Users also can export to self contained templated (tar.gz) HTML, to .odt (OpenOffice rich text format), epub, and screen readable PDF. Other XML output options can be developed as required.

I guess I can never claim to not having project management experience again. Darn it.

On creating a methodology

Some years ago, I developed the Book Sprints methodology. It’s now pretty well defined and is being used very successfully to develop many books for all types of organisations. I am now working on another methodology – Collaborative Product Development. So, this time round, it’s sooo much easier and I thought perhaps I should write down some of the journey from zero to methodology. It will certainly help me to do so and maybe someone else out there will find it useful.

First of all, methodologies are odd things. Book Sprints is a methodology but, at the same time, I often wonder exactly what this means? I mean…you can’t just take a written template and turn it into a successful facilitated process. It just doesn’t work. The reason is because facilitation is a little, if you pardon the strange analogy, like administering the law. The law exists on paper but every time it is administered by a judge it is new. The context requires the law to be interpreted to enable it to be applied.

I think facilitation is like this. You can take a method and apply it but the context is everything. You must always make the application of the method new each time it is applied. Further, you need to extend it and break it when necessary and you have to do it effectively, other wise you break the process and, in the facilitation game, process is everything.

So…you must first be a facilitator to apply a facilitation methodology. Even then you can still screw it up. For example Book Sprints, and Collaborative Product Design, employ all the same skills that you need for ‘unconference’ facilitation plus more. The more is specifically the skills required to drive people effectively along a finite timeline to completion of the thing you are making. The need to drive product in this manner often freaks unconference purists out because you wield a lot of ‘do it now’ power else you will never get there. ‘Do it now’ power is only subtly used in unconferences, in product-driven facilitation you use it like a hammer.

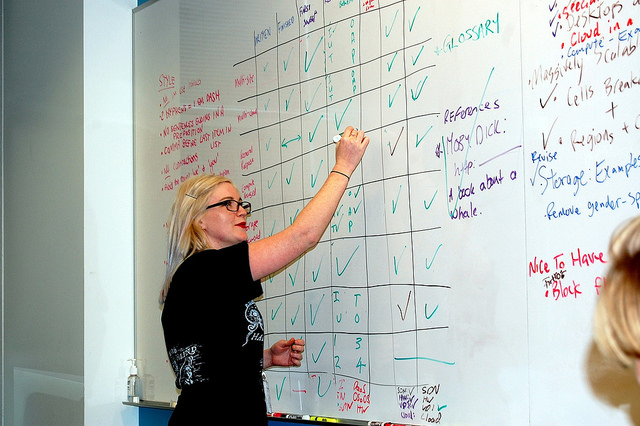

Anyways… the point being that a methodology on paper is nothing. You need to define it, so out comes the pen and paper.

Defining a methodology is actually pretty strange and, in my experience, the newer the ideas in the methodology are to you, the longer it takes to define. Book Sprints, for example, took me about 4 years to work out and I only really knew it had a definition when I had to train someone else. CPD, on the other hand, took me a day to outline on paper. I’m still refining it but that’s normal, the body of CPD came into existence in one day-long session. What’s more, it appears to be working. The bits that are taking the longest to work out are the bits I haven’t experienced before. We haven’t taken a full product to market with CPD, so, consequently, the production implementation phase still needs to be tested and refined. The rest of it, however, seems pretty well constructed.

It took a long time for me to work out a method for Book Sprints. I was really just trying stuff completely blind. It didn’t start that way, as it happens. I first went to people in the publishing industry and asked them how I should do it. I figured they knew how to make books and surely they would have some ideas on how to make it faster. Hah. Was I ever wrong. My experience was that publishing people screwed up the process with their own process. Too much process. So I had to, finally, after a long period of angst, decide I was going to have to work this thing out myself. I didn’t want to do it. I didn’t even know what it was I was trying to do. So, sigh, I relented and proceeded to slug it out.

It was like slugging it out too. I mean, I had no experience in making books. I didn’t want to do anything I considered ‘publishing’. I have an aversion to cathedrals – which is what publishers looked like to me. A deeply institutionalised sect. So I had to actually learn to trust myself and do it my way. It was quite scary at first. I mean, I was inviting a bunch of people to come to some place to work for a week to develop a book using a methodology that actually didn’t exist. I didn’t have much idea what it might look like either. Geez… I must actually be pretty stubborn when I look back on it.

So I went about inviting people to Book Sprints and I challenged myself to trust myself. To listen to myself and observe. I came to understand that the only thing that could enable or prevent a successful Book Sprint was me. There was no other factor. That was pretty frightening at times. I spent many nights during Book Sprints completely terrified that I was about to send this nice group of people into an unproductive deep abyss. They might return from that dark hole but I was pretty sure I wouldn’t.

On this journey, however I had some starting points. I don’t know what triggered it but very early I came to understand that rapid book development of the kind that Book Sprints represents could not be about publishing processes – it was about unconference processes. Luckily I had a mentor, who had, for reasons unknown to me, taken me under his wing. At the time I didn’t know how lucky I was. That was Allen Gunn (Gunner). I had seen him in action many times as a facilitator and I had a few clues to a process. It wasn’t much but it was a start.

So I tried my hand at facilitation. I would, at the time, tell myself that Book Sprints were more about facilitation of people than the production of a book. To say so out loud sounded odd. It didn’t sound true. It sounded like I just made it up. But I kept saying it and trusting it. I kept challenging myself to trust myself. It wasn’t easy but as I became used to it, the process became easier.

Anyway, I still couldn’t call this thing a methodology. All I knew was that I was trying things out and formulating some kind of Book Sprints worldview. I think it’s fair to say the worldview was nothing I could articulate. I worked through gut and felt that everything was instinctual. However, I was learning useful tricks. For example, I remember Gunner saying he tried something new each time he facilitated an event. So I tried something new each time. I learned that if you failed with the something new, the trick was to make out like it was a success and, further, an expected success. This way I created a fallback framework that would allow me to experiment, to try and fail, to learn on the job and to get away with it.

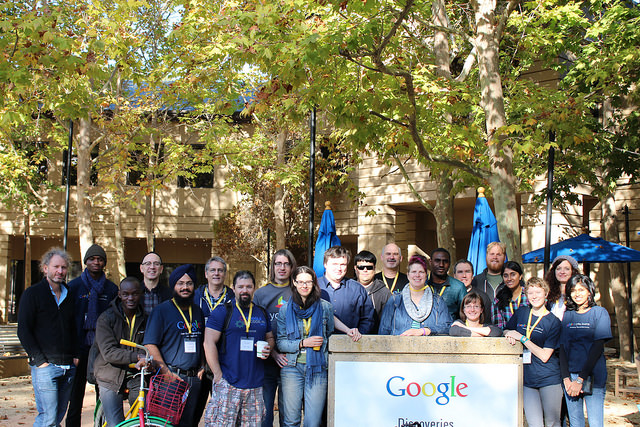

So, I iterated forward. Rather slowly really. I mean, I had to convince people that this non-existent Book Sprint thing was not only possible, but they should do it, while I had little to point to as proof. Yeesh. Talk about a hard sell. But some people saw the possibilities and tried it out. I am forever grateful to Leslie Hawthorn who was working at Google Open Source Programs Office at the time. Leslie (introduced to me by Gunner) backed me and sponsored the first 3 Book Sprints. Amazing. I got something I could start with and that was critical. Later, with a few under my belt, it became easier to convince others.

So I did this for many years and felt I something taking shape. It was actually working. The books were getting better which seemed to indicate I was improving the process. I was starting to construct an embedded framework and the things I did were tested against it. It was filling out and becoming more consistent. I could finally start becoming a little more playful with the process. Still, when I started to talk about it as a method it was a query more than a statement. I wasn’t even sure what a methodology was. I wasn’t sure if Book Sprints was a method or even a stable set of practices. Others also said they same thing. David Berry and Michael Dieter, two good friends and critical theorists, would ask me what I thought it was. I had no idea how to articulate it. I asserted at time that it was a methodology but I wasn’t even sure I convinced myself.

A critical break through came when David and Michael (who had both been to 2 Book Sprints by this time) wrote a post about the process:

http://ausserhofer.net/2013/02/the-method-of-book-sprints/

I was amazed. They saw things that I didn’t. It was stunning to me. They had given me my own framework. From this point I started to construct a much better understanding of what I was doing.

The next step that finally defined the process was when I actually had to train someone to do it. I had other work offered to me (designing platforms) and I had a Book Sprints client base to keep happy. So I needed to scale. I needed me times 2. So I brought in Barbara Rühling (as introduced to me by Zara Rahman). It was at this moment, during a Book Sprint in Malta, and Barbaras first training session, that I started to make up a language to explain what a Book Sprint was. It flowed out of me like I knew it all along. I was very lucky in that Barbara trusted my narrative. It allowed me to expand notions as they came out of my mouth. I could define and refine a language and process as I spoke. It was fantastic and it was the final moment in the long process of defining a method. Hard won experiences were suddenly made salient and coherent though in situ explanation.

Now when I look at Book Sprints it appears pretty concrete. I laugh when people talk about it as if its a ‘known thing’. How can it be? I just made it up! 🙂 Of course, I didn’t just make it up. It is the result of a lot of trial and error and observation, risk, stress, unbelievable elation when things worked out, and the inability to give up. I still don’t know why I didn’t give up. I like to think if I did it again I’d give up. It might be a better way to live my life 😉

Some publishing systems I have developed

I recently went over some publishing systems with Yannis and Christos from Coko. We looked at various systems and discussed them. As we did this, I realised that I’d actually built quite a few! Although we weren’t just talking about those I had built, I began to think through what I had done right and wrong when building those earlier systems. Each development is a learning process and you will always get things both wrong and right at the same time. The trick is to get less wrong the next time round…

In the ten years that I have been building these systems, I have worked with some pretty talented people, including Luka Frelih, Douglas Bagnall, Alexander Erkalovic, Johannes Wilm, Remko Siemerink, Juan Gutierrez, Lotte Meijer, Fred Chasen, Michael Aufreiter, Oliver Buchtala, Nokome Bentley, Andi Plantenberg, Mike Mazur, Rizwan Reza, Gina Winkler and many others including the entire team of Coko – the most talented bunch of them all. Coko team:

Kristen Ratan – CoFounder, San Francisco

Jure Triglav – Lead PubSweet Developer, Slovenia

Richard Smith-Unna – PubSweet Developer, Kenya

Yannis Barlas – PubSweet Frontend Developer, Athens

Christos Kokosias – PubSweet Frontend Developer, Athens

Charlie Ablett – INK Lead Developer, New Zealand

Wendell Piez – XSL-pro, East Coast USA

Julien Taquet – UX-pro, France

Henrik van Leeuwen – Designer, Netherlands

Kresten van Leeuwen – Designer, Netherlands

Juan Guteirez, Sys Admin, Nicaragua

Alex Theg – Process, San Francisco

All systems except, unfortunately, one (see below) are open source.

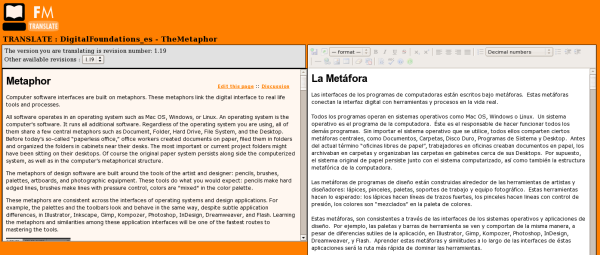

FLOSS Manuals

The first publishing system I designed and built didn’t have a name really. It was the glue behind the FLOSS Manuals English site. FLOSS Manuals was, and is still, a community focussed on building free manuals about free software. I started the development in English but the system needed to be useful to a number of different language communities, of which Farsi was the most interesting. Today, only the French and English communities are still operational.

I built the FLOSS Manuals system in Amsterdam in about 2006. It was based on TWiki, an open-source Perl-based wiki. I chose TWiki because back then it was the only wiki around that had good PDF-generation support – I think this came from some of its plugins. TWiki had a good plugin and template system and I came to think of it as a rapid prototyping application – it was pretty malleable if you knew how. I was a crap programmer so I cut and pasted my way to a system that became usefully functional.

I leveraged the account creation and permission systems of TWiki, and ripped out the wiki markup editing and replaced it with an HTML WYSIWYG editor (I think it was TinyMCE). So in wiki world terms I had committed something of a crime. Throwing out wiki markup at the time was unheard of in the post-2004 euphoria of Wikipedia. But JavaScript WYSIWYG editors were coming along just fine, and I thought wiki markup no longer made any sense (in fact it had been invented to make making HTML easier than writing raw HTML). But y’know… wiki markup was no easier than using a WYSIWYG editor, despite the sacred status of Wiki markup in the Wikimedia community. And despite my heresy,the Wikimedia did give me a barnstar for my efforts, which was nice of them:)

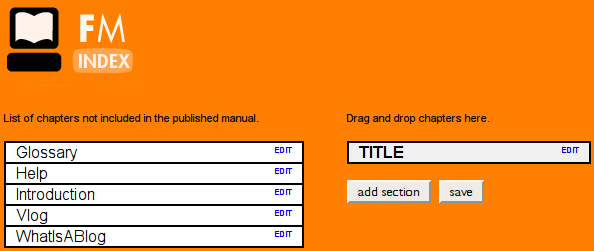

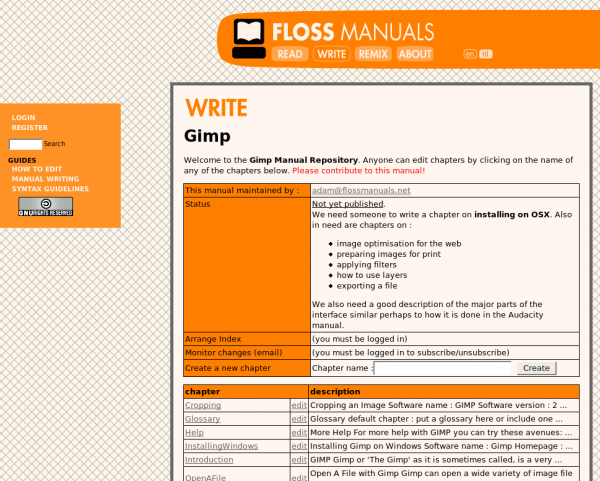

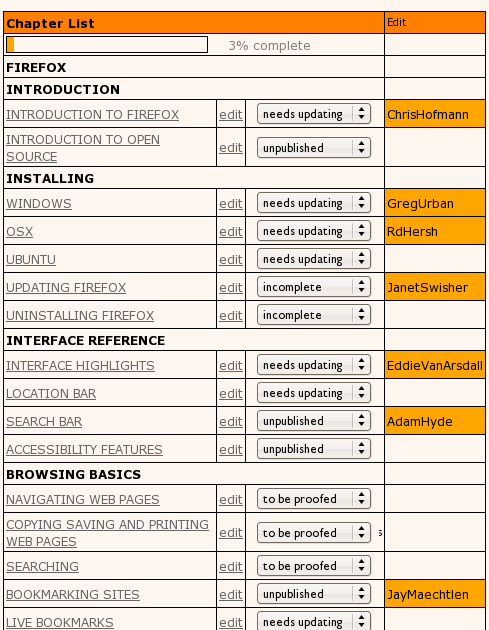

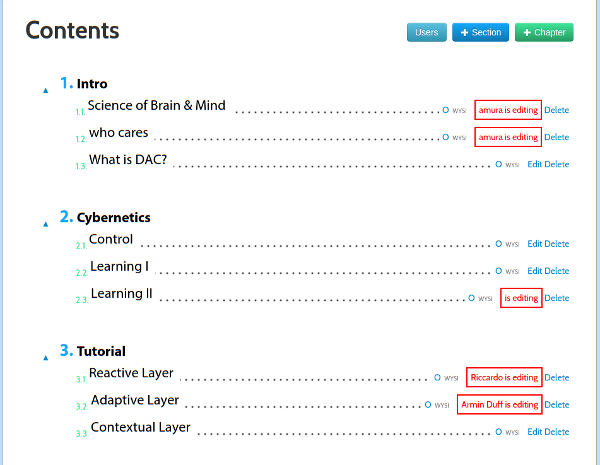

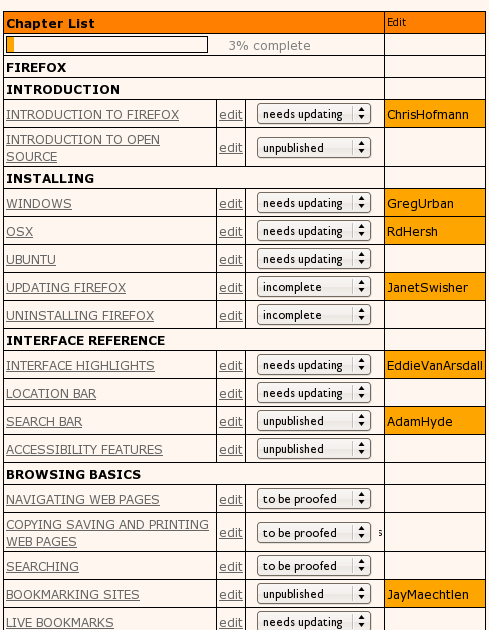

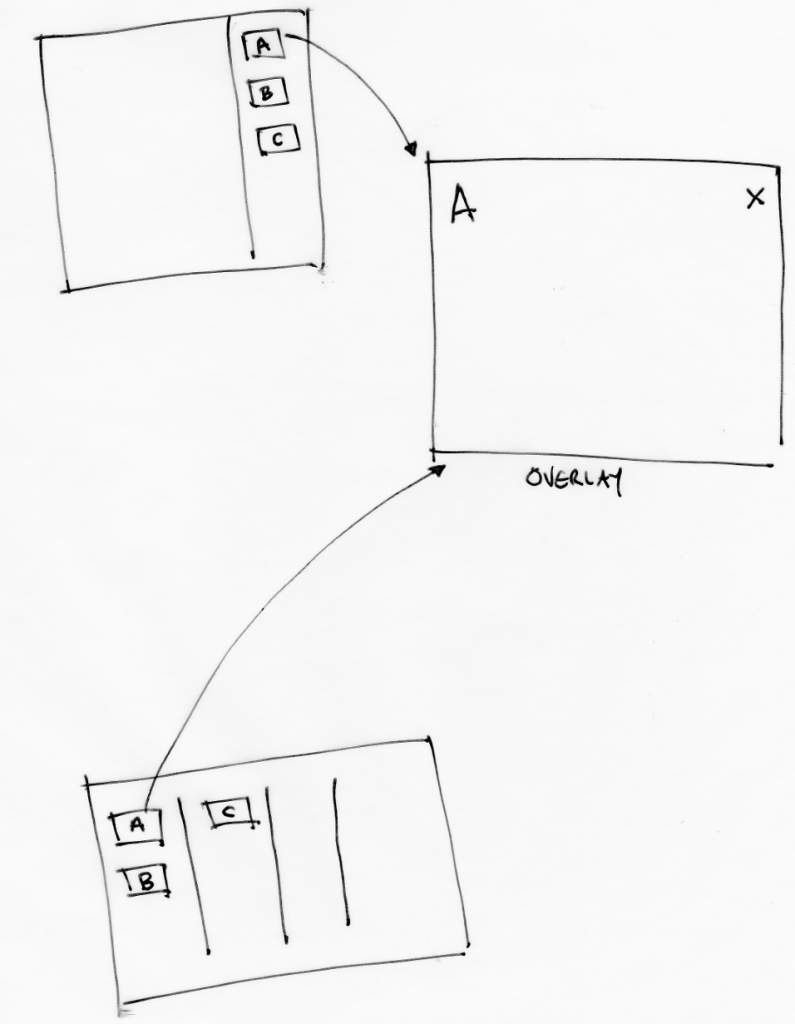

After I reached the limit of my coding skills, a friend, Aco (Alexander Erkalovic), helped build the next bits. I found some money to pay him and that is when things started to move forward. I can’t remember all parts of the system, although it’s still in up and running for some FLOSS Manuals language sites. The core of the system was the manual overview page. This contained a list of all chapters in a manual. You could also set the status, add new chapters, view overall progress etc. from this one page. We had a separate mechanism for creating an ordered table of contents (index) for a manual.

Index builder, essentially a dynamic drag and drop mechanism for arranging chapters

The overview page

Essentially, you added a chapter on the overview page and then opened the index builder and arranged the chapters. When saved, the (refreshed) overview page displayed the correct (new) order of chapters. We had to do it like this because back then, in the era of the ‘page refresh,’ it wasn’t possible to synchronise dynamic elements across multiple clients. So we couldn’t have one ‘shared’ index builder that would dynamically update all user sessions simultaneously. Nevertheless, it worked pretty well.

From the overview page, you could choose a chapter to edit. When you did so, you locked the chapter and, through some JS trickery Aco cooked up, we wereable to do this across multiple clients so everyone could see in real time who was editing what.

When editing a chapter, you could save the document and then, when ready, publish it. This way you could have an ‘in progress’ state of a chapter and a published state. At publish time the chapter was copied across to the system’s web delivery cache.

We also added chapter status markers, as you can see from the above image. It was pretty basic but nifty.

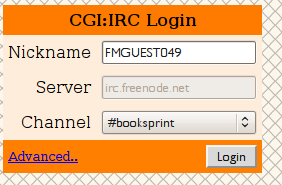

Next I hacked in a live chat, initially using IRC (freenode) for a global FLOSS Manuals-wide chat:

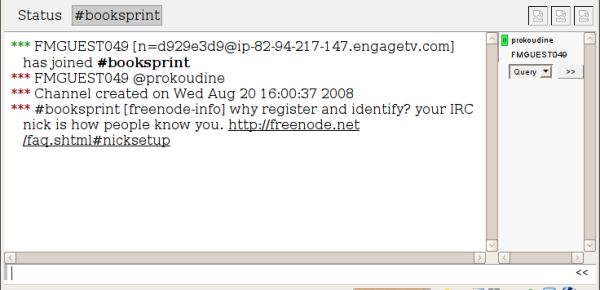

Then I hacked a fancy AJAX script into the chapter edit interface so each manual could have its own chat with the interface present while you were editing a chapter. It also looked a little nicer than the IRC channel. From the beginning, I tried to make everything look like it was meant to be there, even if it was a fiddly hack.

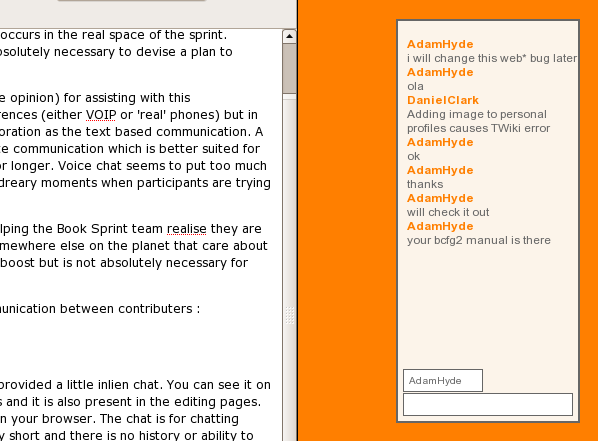

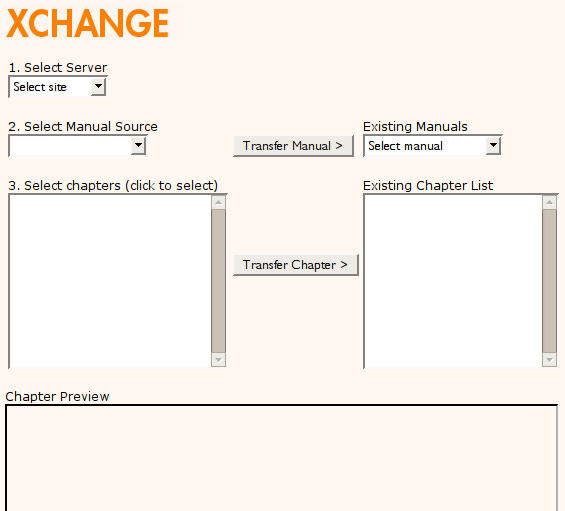

FLOSS Manuals also had a lot of other interesting goodies. We had federated content, for example. This was established so one language site could import an entire manual from another and set up a translation workflow.

We also had a simple side-by-side editor set up for translation that worked pretty well for translators.

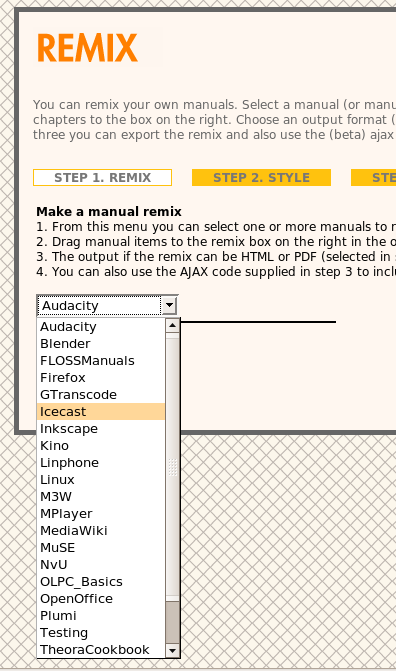

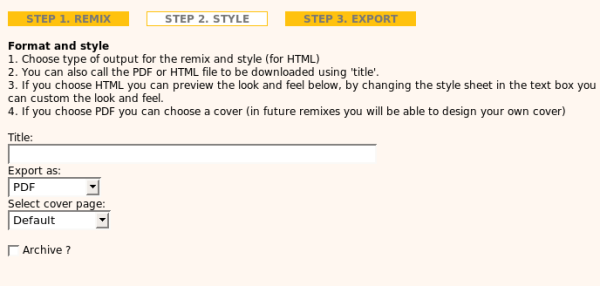

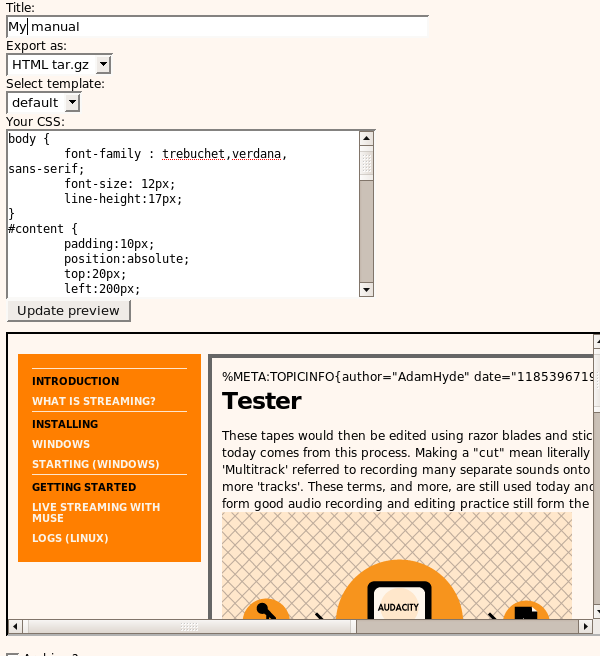

In addition, we had a remix system for generating new versions using mixed content from other manuals. This was useful for workshops and for making personal manuals, for example.

In addition, we had a remix system for generating new versions using mixed content from other manuals. This was useful for workshops and for making personal manuals, for example.

One of the cool things about the remix is that you could output in many formats such as PDF and zipped HTML, add your own styles through the interface, PLUS you could embed the remix in your own website 🙂 The embed worked similarly to methods used today to embed YouTube or Vimeo videos in websites (by cut and pasting a simple snippet). The page delivery was ‘live,’ so any updates to the original manual were also displayed in the embed. I thought that was pretty cool. No one used it of course 🙂

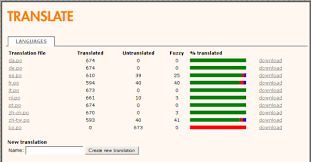

The system also had diffs so you could compare two versions of a chapter. It was good for seeing what had been done and by whom. In addition, it was possible to translate the user interface of the entire system to any language using PO files and a translation interface we custom built:

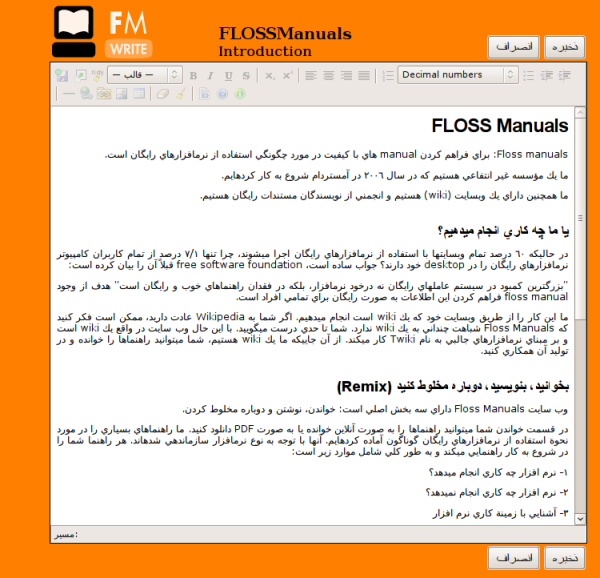

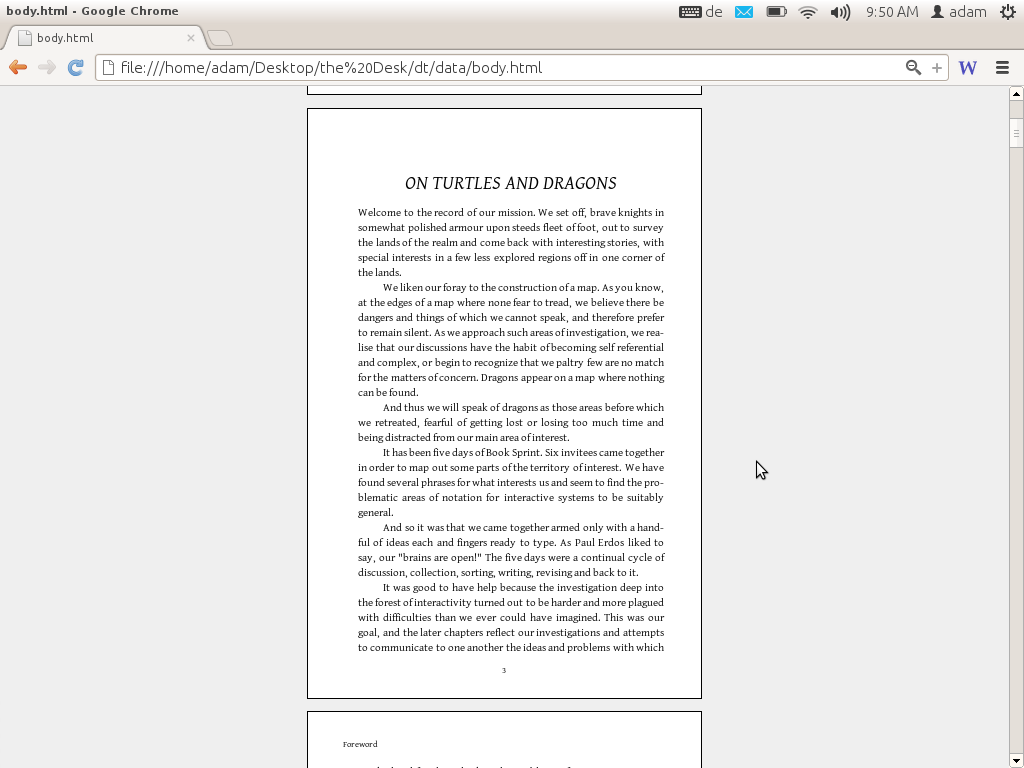

But by far the most interesting thing for me was building FLOSS Manuals to support Farsi. It was interesting because, at the time, no PDF-renderer I could find would do right-to-left rendering. Behdad Esfahbod advised me to just use the browser to do it. Leslie Hawthorn from Google Open Source Programs Office introduced me to him after I went on a naive search in the free software world for ‘someone that knew something about RTL in PDF’. I was very lucky. The guy is a generous genius. He just suggested an approach a new way to think about it and later I worked with Douglas Bagnall (see below) to work out how to do it. The basic idea being that HTML supported RTL and the PDF print engines rendered it nicely…so…it was my first realisation that the browser could be a typesetting engine.

But by far the most interesting thing for me was building FLOSS Manuals to support Farsi. It was interesting because, at the time, no PDF-renderer I could find would do right-to-left rendering. Behdad Esfahbod advised me to just use the browser to do it. Leslie Hawthorn from Google Open Source Programs Office introduced me to him after I went on a naive search in the free software world for ‘someone that knew something about RTL in PDF’. I was very lucky. The guy is a generous genius. He just suggested an approach a new way to think about it and later I worked with Douglas Bagnall (see below) to work out how to do it. The basic idea being that HTML supported RTL and the PDF print engines rendered it nicely…so…it was my first realisation that the browser could be a typesetting engine.

Implementing RTL in the FLOSS Manuals system was so very tricky, and I was unfortunately on my own for working out Farsi regex .htaccess redirects and other mind-numbing stuff. Just trying to think in right-to-left for normal text did my head in pretty fast, but somehow I got it working.

Outputs of all language books were PDF and HTML, later also EPUB. I initially used HTMLDoc for HTML-to-PDF conversion. It was pretty good but didn’t really think like a book renderer needs to. This was my first introduction to the overly long wait for a good HTML-to-PDF typesetting engine. Later I found some money and employed Luka Frelih and then Douglas Bagnall to make a rendering engine separate from the FLOSS Manuals site (see Objavi below). Inspired by my chats with Behdad (above) Douglas introduced some clever PDF tricks with the Webkit browser engine to get book formatted PDF from HTML. I can’t remember exactly how he did it but essentially he used xvfb frame buffer to run a ‘headless browser’. In short, and for those that don’t know those terms, he came up with a very clever way to run a browser on a server to render PDF. It did it by rendering HTML to PDF in pages (using the browser PDF renderer) and then rendered another set of slightly larger blank PDF with page numbers etc and embedded one within the other. Wizard. Hence we were able to make PDF books from HTML. It also supported RTL 🙂 I think I need to say here that this whole process was immensely innovative and we did it on a dime. Also, because we refused to use proprietary systems we were forced to innovate. That was a very good thing and I welcomed the constraint and the challenge.

Later we also used WKHTMLTOPDF to make PDF. It worked and we worked with that for a long time. I even tried to start a WKHTMLTOPDF consortium with Jacob Trulson, the founder of the project, it got some way but not far enough (I am very happy WKHTMLTOPDF is still going strong!).

I played a lot with Pisa and Reportlab for generating PDF and finally cracked it when I started book.js (more on this below). Actually, when it comes down to it I think I used everything that wasn’t proprietary to make book formatted PDF from HTML. It was the start of a long love affair with the approach. I promoted this approach for a long time, even calling for a consortium to be formed to assist the approach:

http://toc.oreilly.com/2012/10/the-new-new-typography.html

http://toc.oreilly.com/2012/11/gutenberg-regions.html

As it happens, all this time later I’m still doing the same thing 🙂

http://www.pagedmedia.org

We integrated FLOSS Manuals with the Lulu API (now defunct). This allowed us to generate books automatically from HTML using Objavi (below) and they would be automagically uploaded to the Lulu print-on-demand marketplace for sale…that was amazing! Ah…but also no one used it. Lulu shut down the API as soon as they realised no one was using it.

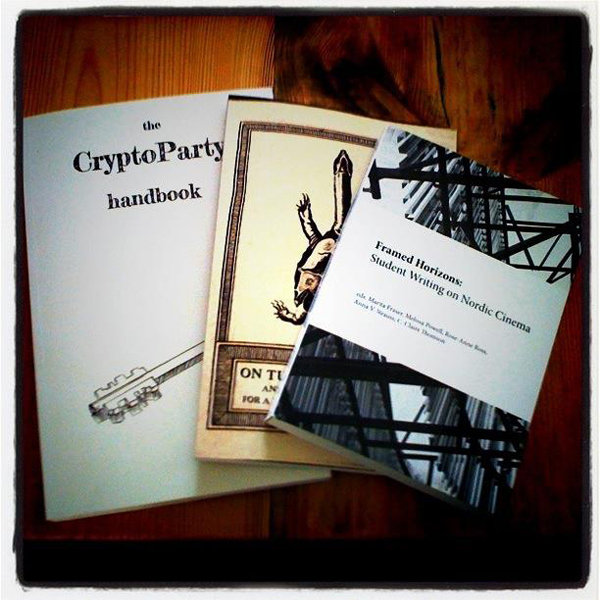

We made many many manuals with this setup. Many of them printed from the auto-PDF magic and were distributed as paper books. Many of the books were in Farsi. The One Laptop Per Child community even built a FLOSS Manuals app that was distributed on all OLPC laptops with the documentation made with FLOSS Manuals.

The system produced loads of manuals and printed books about free software. All free content.

The FLOSS Manuals platform didn’t have a name. It was a hack of TWiki. While you could get all the plugins online, it would have been a nightmare to deploy. I did deploy it many times but I essentially copied one install to another directory and then cleaned out all the content and user reg etc. and went to town rewriting all the .htaccess redirects. It sounds stupid now, but I spent a lot of time doing URL redirects to ditch the native TWiki URLs (which were extremely messy) and make them readable. Hence the system was a pain to deploy or maintain. It was feeling like we needed a standalone, dedicated, system….

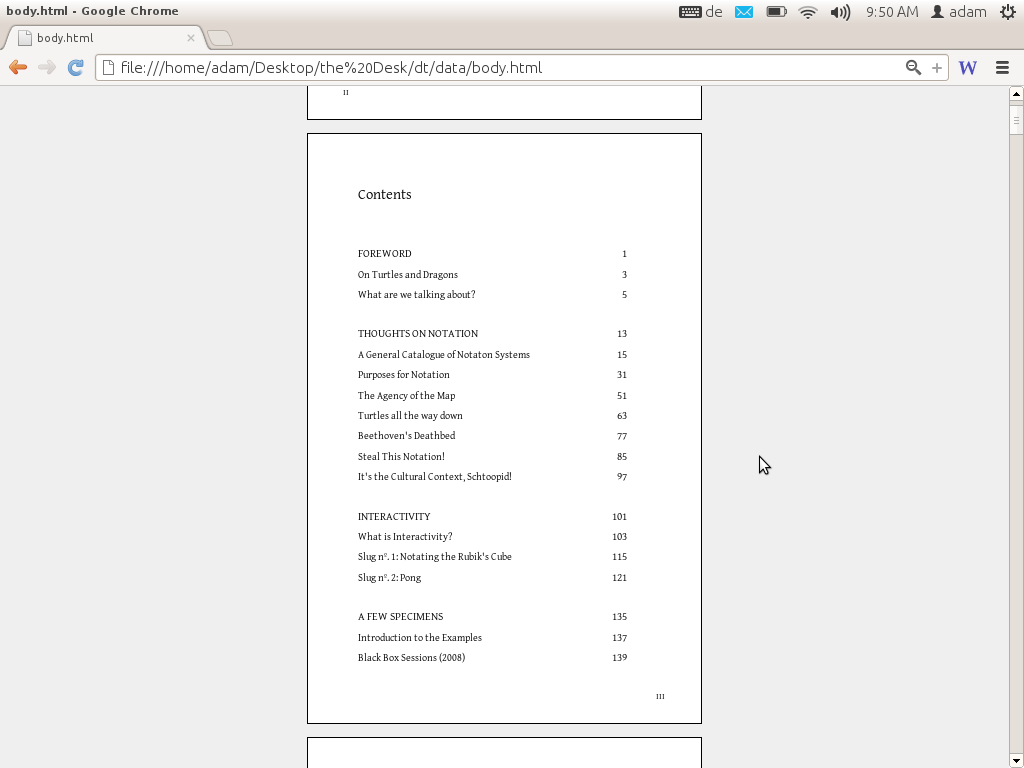

Booki

Booki was the next step. It was clear we needed something more robust and also it was clear no web-based book production system existed, hence the hackery Twiki approach. So it was about time to build one. At the time, though, I remember it being very difficult to convince anyone that this was a good idea. I didn’t have access to publishers, and everyone else thought books were just soooo 1440. What they didn’t realise is that we were building structured narratives and that, IMHO, will have a lot of value for a long time. Call it a book or not. Anyway, we built Booki on Django (a Python framework) and the first time we used it was a Book Sprint for the Transmediale Festival in Berlin.

Aco literally would be building the platform as it was being used in the Book Sprint – restarting when everyone paused to talk. It was an effective trick. We learned a lot working with the tool and building it as it was being used.

At the time I couldn’t imagine book production being anything other than collaborative. FLOSS Manuals collaboratively built community manuals. Book Sprints were short events building books collaboratively. So Booki was meant to be all about collaboration. Booki also was run as a website (booki.cc) which was freely available for anyone to use.

Many groups used it which was cool.

Booki.cc run from with the OLPC laptop

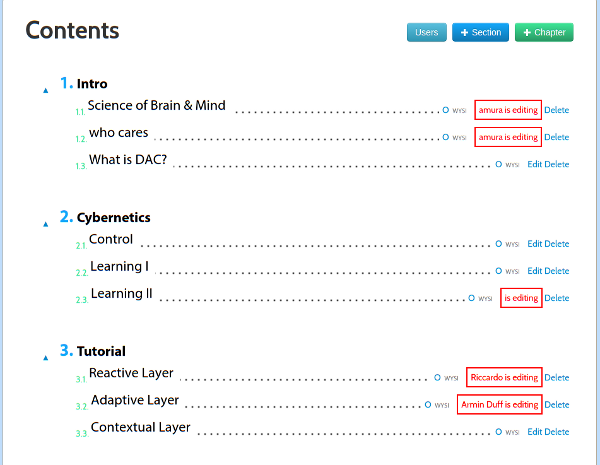

Booki had all the basic stuff the FLOSS Manuals system had and we advanced the feature set as our needs became more sophisticated, but the basics were really the same.

The main differences were that we had a dynamic ‘table of contents’ where you could add and rearrange chapters etc and the updated ToC would be dynamically updated across all user sessions. Hence the ToC became a kind of ‘control panel’ for the book.

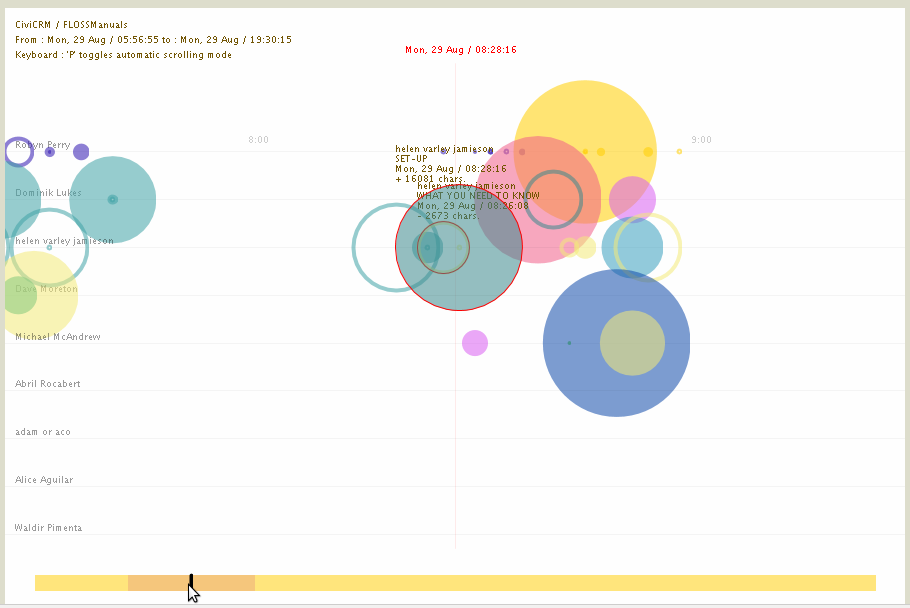

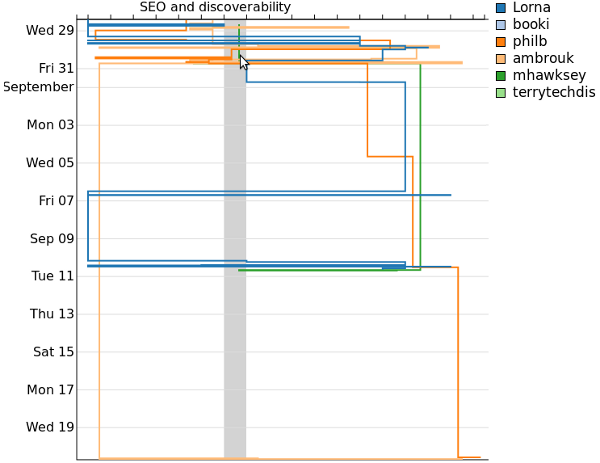

We also experimented with data visualisations of book production processes.

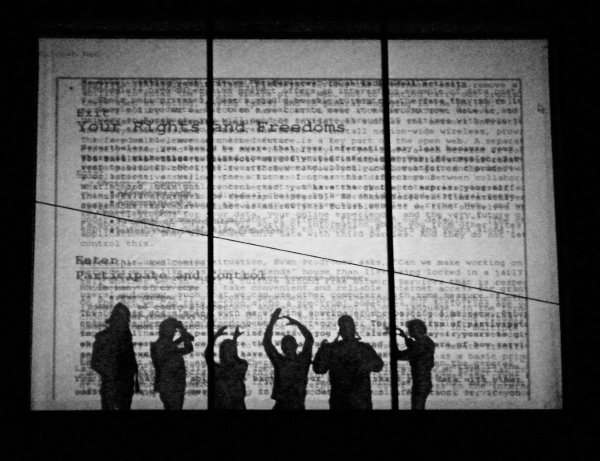

We did some cool stuff with the visualisations. For example, during the Open Web Book Sprint (also in Berlin) we worked in the Hungarian Embassy. They had a huge window that you could backwards project onto so people could see the projections on the street. So we made a visualisation of text from the book being overlayed as we wrote it. Below is an image shot with us standing in front of the projector…I mean..c’mon…how cool is that? 🙂

Booki also had federation. You could enter the target URL of a book from another install and Booki 1 would make a portable archive (booki.zip) and send it to Booki 2. Booki 2 then unpacked the zip and populated the book structure complete with images etc. I liked the idea very much of using EPUB instead as a transport technology instead and was later able to do so for Aperta and PubSweet 1 (see below).

In general, Booki didn’t advance much further from the FLOSS Manuals set up. It kind of did ‘more of the same’. I think the only stuff that went further than the previous system was the dynamic table of contents plus it was easier to install and maintain. Having groups was also new, but that wasn’t used much. It was in some ways just a slightly different version of the previous system.

Booki was also used for producing a tonne of books.

Objavi 1 & 2

Alongside the development of the FLOSS Manuals system and Booki, I headed up the development of Objavi. Objavi is basically a separate code base that was used as a file conversion workhorse. Objavi 1 was a little bit of a hacky maze but it did a good job. It would basically accept a request and then pipe that through a preset conversion pipeline. It did a good job. What I found most useful from this is that each step left a dir that I could open in a browser to inspect the conversion results. So if the conversion needed several steps, this was very helpful in troubleshooting.

Objavi 2 was meant to be an abstraction. However I don’t think it really got there, and Booki, which later became Booktype, came to internalise these conversion processes after I left the project. I always thought internalising file conversion was a bad idea because file conversion is resource-intensive, making it better to throw it out to another external service. And having a separate conversion engine enables you to completely overhaul the book production code without changing the conversion code. Hence FLOSS Manuals could migrate to Booki but still use the same external conversion engine. This was a HUGE advantage. Further, all the FLOSS Manuals instances, as well as booki.cc could use a single Objavi install for their conversions.

Objavi was actually also the magic behind the federated content in both the FLOSS Manuals system and Booki. All content would be passed through Objavi for import and export so Objavi became the obvious conduit for passing a book from one system to another. This gave me a lot of ideas about federated publishing which I have written about elsewhere and archived here.

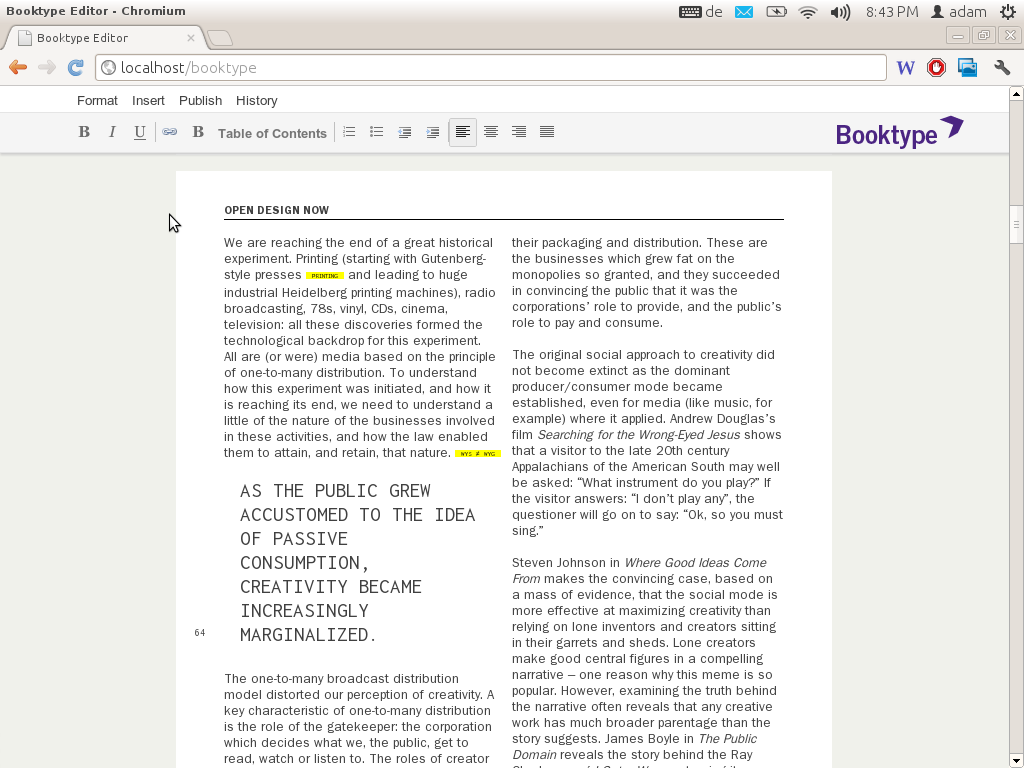

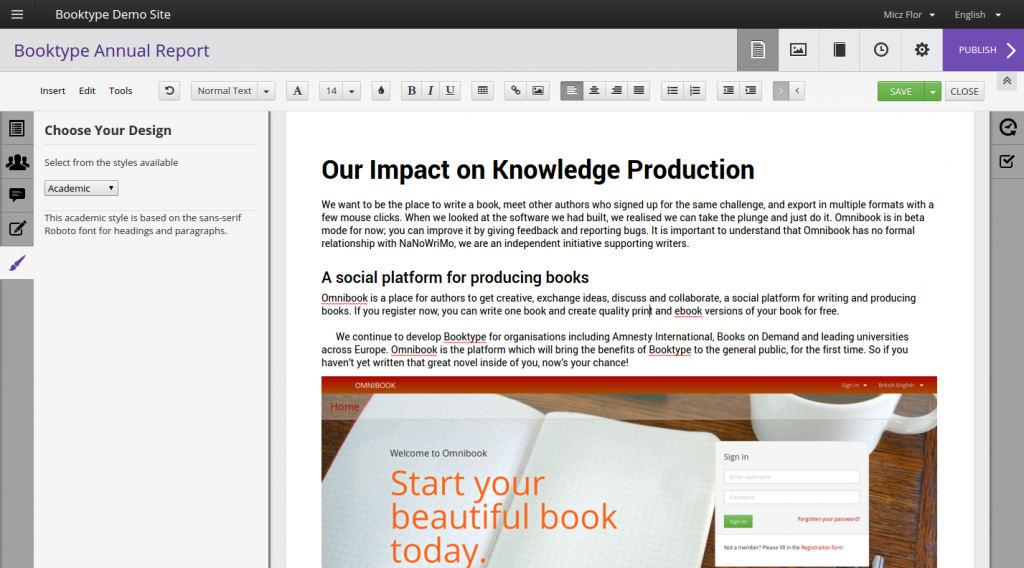

Booktype

Booktype was really Booki taken to market. I was frustrated by not getting much uptake, so I took Booki to Sourcefabric in Berlin and headed up the development there. Booktype gained a UX cleanup. The editor was changed after an event I organised in Berlin called WYSIWHAT. The event was meant to catalyse energy around the adoption of a shared editor for many projects. It was of many things I did in pursuit of the perfect editor. At that event, we chose the Aloha contenteditable editor. I don’t think that was as useful a change as expected at the time, but back then contenteditable looked like the way to go despite there being few editors that supported it. Since then TinyMCE, CKEditor and others all have contenteditable support, further econtenteditable became a bit of a lacklustre implementation in browsers.

Booktype was literally the same code as Booki but rebranded. So many of the same features persisted for quite some time until Booktype eventually took on a life of its own.

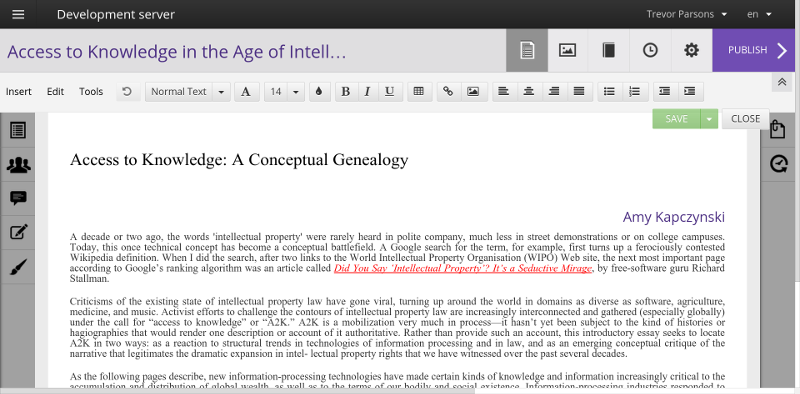

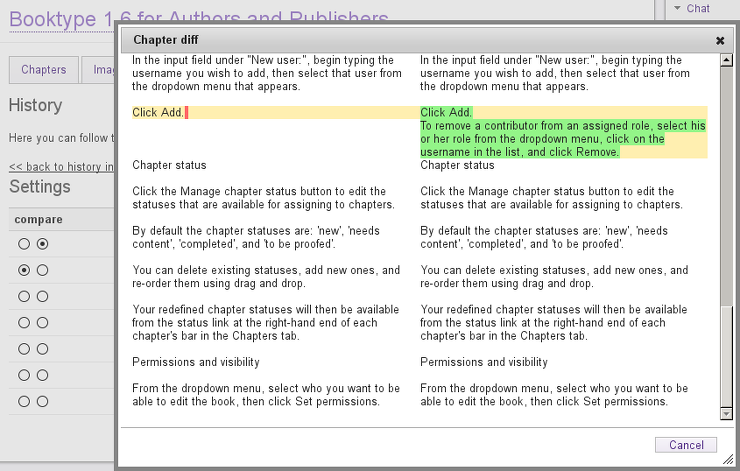

Displaying ‘diffs’ (differences) between 2 different versions of a chapter

Activity stream of a book

I prototyped some interesting things in Booktype but not much of it got built. For example, I was keen on editing content in the style of the final output. The example below is using the CSS layout of Open Design Now which I mentioned below with reference to BookJS.

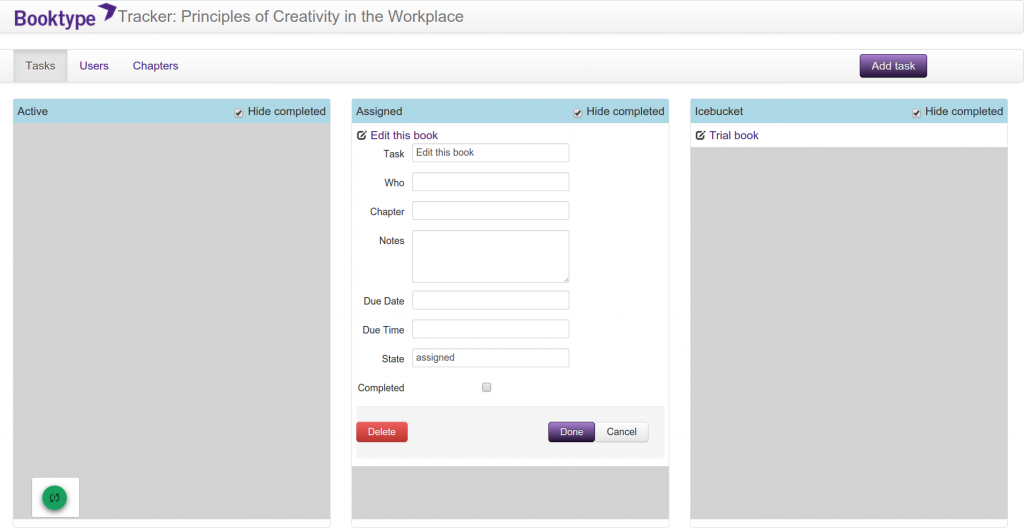

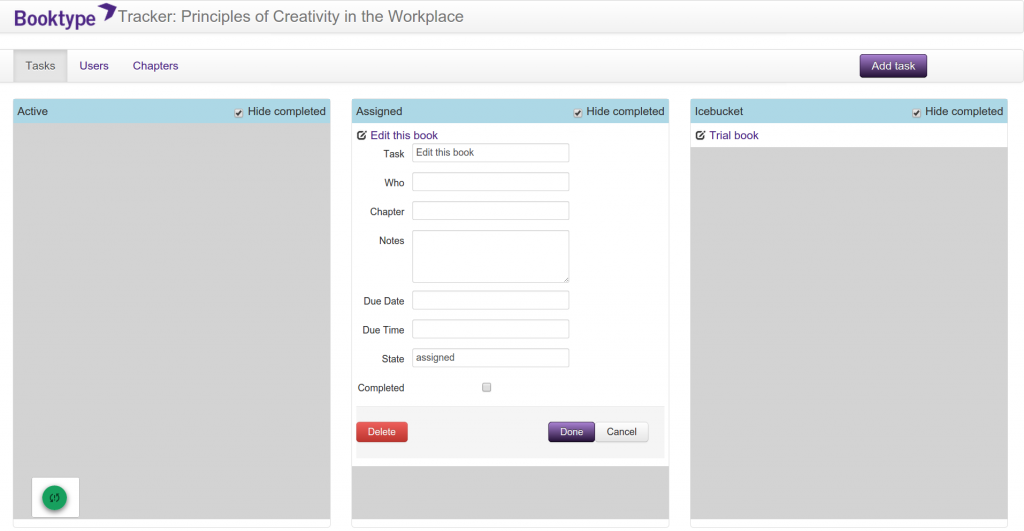

I also made a task manager prototype based on kanban cards but it was never integrated into Booktype.

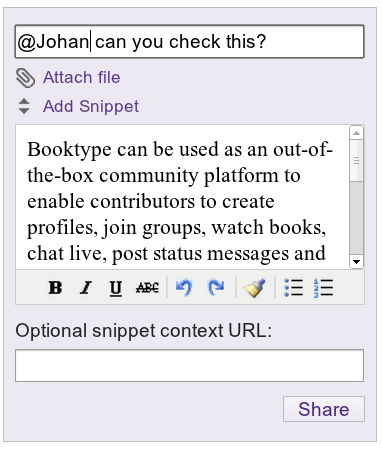

I think there are only really three parts of Booktype’s development that occurred while I was in charge of the project. First was the integration of a short messaging system into a user’s dashboard and into the editor. Essentially you could highlight text in a chapter, click on the msg widget and a short message could be sent with that text to whoever you wanted (in the system). It was intended for fact checking or editing snippets etc. The snippets were loaded into an editor to assist with this kind of use case.

A good idea but seldom used.

In addition, Booktype supported groups, so users could form groups which were populated by users and books. The idea behind this was that you could form a group to work on a collection of books collaboratively.

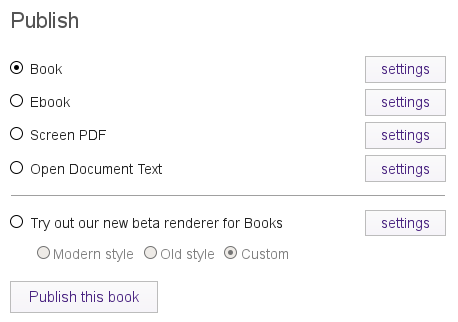

Lastly, the renderer was integrated in a more sophisticated way so you had more control of the output from within Booktype. Essentially you could choose a number of output options and style them from within Booktype.

These were all interesting additions, but in the end, Booktype was really only Booki taken a step further as a product without offering much that was new. I think we should have probably actually removed a lot of things rather than adding new things that didn’t get used.

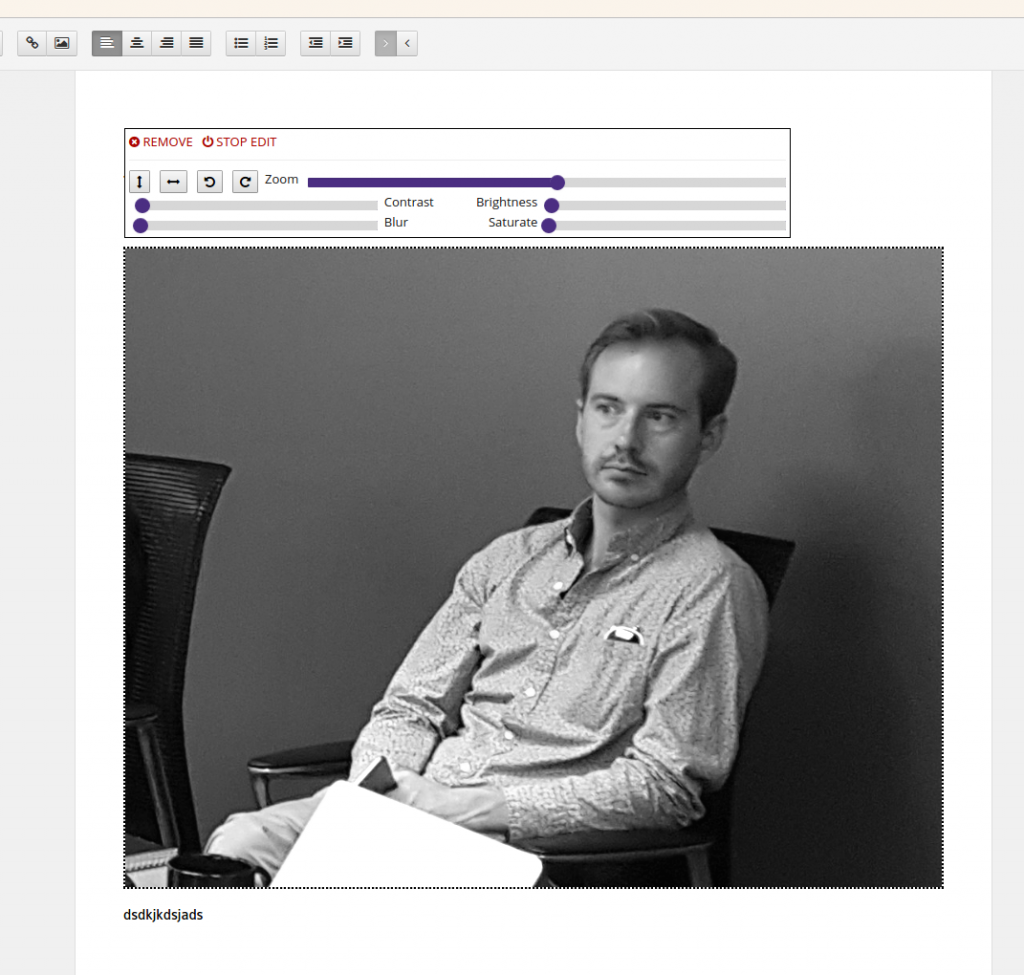

Booktype developers added some interesting stuff after I left. I particularly like the image editor and the application of themes to the content.

The image editor enables you to resize and effect an image from within the chapter editor.

The theme editor allows you to choose from an array of styles/themes and edit them.

Booktype 2 has since been released. It has become a standalone business and is doing good work. Also, the Omnibook service is a ‘booki.cc’ online service based on Booktype 2.

Booktype has been used by many organisations and individuals to produce books.

I think Booktype 2 is good software but I didn’t particularly like the direction of the Booktype UX after I left the project – it was becoming too ‘boxy’ and formal. ‘Good UX’ is not necessarily good UX. So I eventually developed another system with a much simpler approach, specifically for using with Book Sprints (but it has had other uses as well). More in this in a bit.

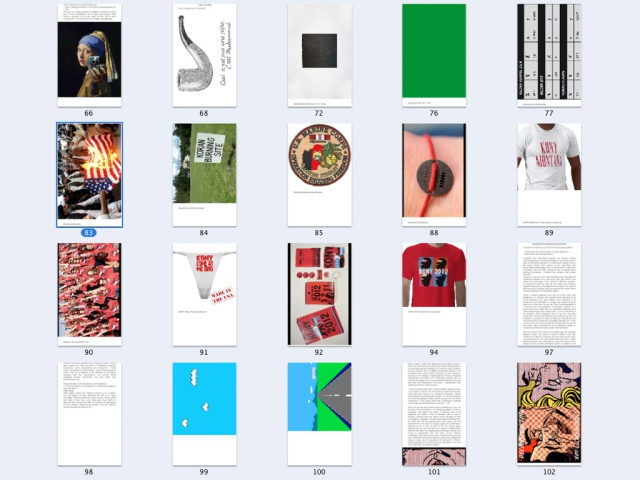

book.js

One innovation, and a further exploration of using the browser as a typesetting engine, that resulted from my time with Booktype is book.js. Essentially I had been looking for a new way to render books from HTML using the browser. I wanted to understand how Google docs could have a page in the browser and then render it to PDF with 1-to-1 accuracy. Surely the same could be done with books? However, no one could tell me how it was done. So I researched and eventually found out about the nascent CSS Regions that would allow you to flow text from one box to another in HTML. I worked with Remko Siemerink at a workshop in Amsterdam to explore PDF production from CSS. We made an interesting book with some of the Sandberg designers.

After more research and breaking down what I thought could happen, Remko worked with CSS Regions (& js) to replicate the page design of a book called “Open Design Now.” It was amazing. He got the complex design down plus it was all just HTML and CSS, it looked like a page AND when printed from the browser it retained a 1:1 co-relation. Awesome.

The following summer I was able to employ someone for Booktype to work on the tech and I hired a developer (Johannes Wilm) to work on the PDF rendering. From there we eventually had BookJS that enabled in-browser rendering of books which could then be exported to print-ready PDF by just printing from the browser. Whoot!

After time, BookJS (original site still available) could also formulate a table of contents etc. It was, and is, pretty cool and IMHO is the right way to do this. Unfortunately, Google Chrome decided to discontinue CSS Regions so if you now want to use BookJS you have to use a very old version of Google Chrome. However, better technologies have come along that support the same approach, namely Vivliostyle (which Johannes later worked on).

Github Editor

During the time with Booktype, I also did some experiments in other processes. One was using Github as the store for an EPUB and using the native zip export that Github offered to output EPUB (since EPUB is just a zip formatted in a specific way). Juan Gutierrez put together a quick demo and I published about it here:

http://toc.oreilly.com/2013/01/forking-the-book.html

Sadly the demo is no longer available but later a good buddy, Phil Schatz, adopted the idea and built something similar and (I think) much better:

http://philschatz.com/2013/06/03/github-bookeditor/

PubSweet 1

Since Booktype was going its own way, I wanted to develop a new, lighter, system for Book Sprints. Hence Juan and I worked out PubSweet, a simple PHP-based system. This would later be reformulated as a JavaScript system (see below).

PubSweet was very simple. Essentially 3 components – a dashboard, a table of contents manager, and an editor. It would later evolve to include more features but it was really the same as the systems I had developed earlier, though simpler. I wanted to get to a cleaner interface and bare basic features. I also wanted to retain some book elements, hence the table of contents manager looks a little like a book table of contents (except the garish colors ;).

PubSweet 1 is still in use by the Book Sprints team and functions well. It uses BookJS for rendering paginated books and for PDF rendering straight out of the system. It can also generate EPUB directly. Apart from that, it is pretty simple and effective. I used a basic card-based task manager for this, based on an earlier prototype I made when working with Booktype. It was a simple kanban type board but we never properly integrated it.

We included annotation using Nick Stennings Annotator project:

PubSweet 1 has been involved in producing more books than I can count, for everyone from OReilly books to Cisco, to the World Bank, UNECA, IDEA etc etc etc

PleigOS

Somewhere along the way, I developed a simple system for creating Pleigos – one-page books created by folding a single piece of paper which has text and images. The system places text and images so that when you fold a single page after printing, a small book is formed. It was more an artistic experiment than anything but it was fun.

http://www.pliegos.net/

Note: the Pleigos project was by my good friend Enric Senabre Hidalgo, I just developed the initial Pleigos software.

Lexicon

The UNDP approached me to build software for developing a tri-lingual lexicon of electoral terminology. The languages to be supported were English, French, and regional Arabic. It sounded interesting so I used PubSweet as the basis for this.

The main difference between Lexicon and PubSweet was that you could choose to create a chapter from 2 different types of editor. Editor 1 (‘WYSI’) was a typical WYSIWYG editor. This was used for producing chapters with prose. The second type of editor (‘lexicon’) allowed you to create a list of terms, each with three different translations – English, French, and Arabic. This opened my eyes to the possibilities of having different types of editors for different content types, a strategy I hope to use again.

![]() The ‘lexicon’ editor in action

The ‘lexicon’ editor in action

The final print output looked pretty good:

![]()

The system enabled a dozen or so people from different Arabic regions to discuss translations and work collaboratively through a list while at remote locations. We built a specific discussion forum for them as part of the system and had up and down voting etc. I liked this project a lot because it was very different from any other project I had worked on yet it employed many of the same strategies.

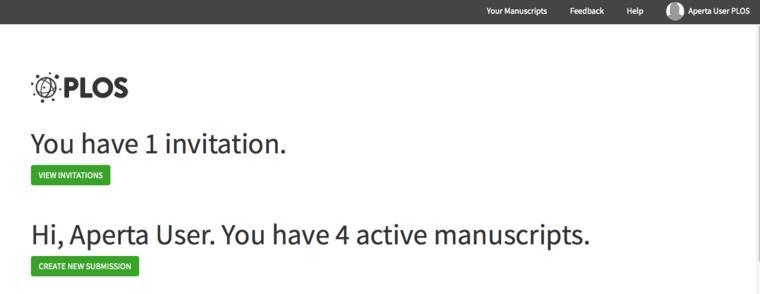

Aperta

Along the way I was approached by John Chodacki of PLOS to build a Journal system for them. I knew nothing about scientific journals, so I went through a process of re-education 🙂 It sounded interesting! I spent a year-and-a-half heading up a team to design and develop this system. This is pretty much the first time I wasn’t scraping together pennies to build a system.

Journal systems aren’t that different from book production systems, in fact doing this project helped me realise that the production of knowledge, in general, follows a particular high-level conceptual schema:

- produce

- improve

- manage

- share

Each artifact (journal article, chapter, book, issue, legislation, grant application etc) follows its own kind of path, with its own unique processes, through these four stages. I have written more about this elsewhere in this blog so won’t go into more detail about it here.

Research articles, (Aperta wasn’t initially intended to deal with Journal Issues which are a collection of articles) come into a Journal as (predominantly) MS Word. They then need to follow a process of checks (eg. to make sure the article is right for the journal etc) before going through the hands of various editors (handling editors, academic editors, etc) and reviewers, including a back-and-forth with the author(s) and a final pass through a production team and/or external vendor to prep the files for publication. The biggest difference I found from my previous experience with book production systems is that there is more to-and-fro involved. Simply put, there is more workflow. So Aperta addresses this with a simple workflow engine based on the Trello/Wekan kanban card-based model.

Aperta was built in Rails with Ember JS. The front end was pretty much decoupled from the backend. It was pretty ambitious and we decided to use the Wikimedia Foundations Visual Editor at the heart of the project. It was the most sophisticated editor available at that moment. I have come to learn that you have to take what you have at the time and work with it. We committed to adopt it and make contributions. I hired the Substance.io chaps (Michael and Oliver) to work on the editor. They did a great job. (Subsequent development of their own editor libs has enabled us to work with them for Coko (more below). )

Aperta’s approach was to simplify the submission process that was managed by Aries Editorial Manager. We leveraged the OxGarage project for MSWord-to-HTML conversion and imported the manuscripts into Aperta. Then workflow templates could be set using kanban cards (as per above). These cards then enabled a flexible method for gathering information (submission data) from the authors at submission time. A lot of time was spent on getting good clean, simple, UX. The kanban card system was very modular – the cards themselves were their own applications, enabling anyone to build a card to their own requirements. This made the cards extremely powerful as they were essentially portable applications.

Further, I developed a model of sorting a lot of cards into columns much like Tweetdeck’s saved-columns model. It was all rather neat. A ton of innovation. Unfortunately, I don’t have any screenshots apart from what I see PLOS has on their website:

http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/s/aperta-user-guide-for-authors

http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/s/file?id=d45b/Aperta-Quickstart.pdf

http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/s/aperta-user-guide-for-reviewers

Aperta is in production now for PLOS Bio but unfortunately the code still isn’t available.

I think Aperta radically rethought how Journal workflows might be managed. I learned a lot through this process and it informed decisions and architecture for the next platform I was to work with – PubSweet 2, developed by Coko.

I also think taking a step into another realm where many concepts were transferable but the use case was different was very good for me. It helped me abstract a few notions. It was also good to build a sophisticated framework in another language and to have the resources to try things out. It was an excellent incubation period where I learned a lot while building a pretty good platform.

During this period I also developed a kind of Objavi 3 but I’m not sure now what it is called or if it is used.

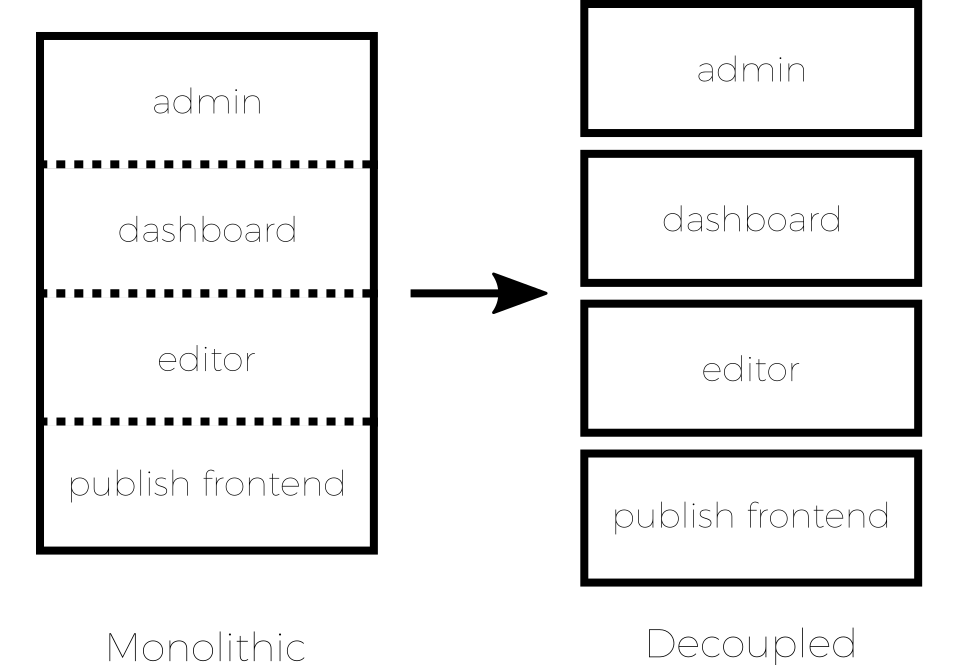

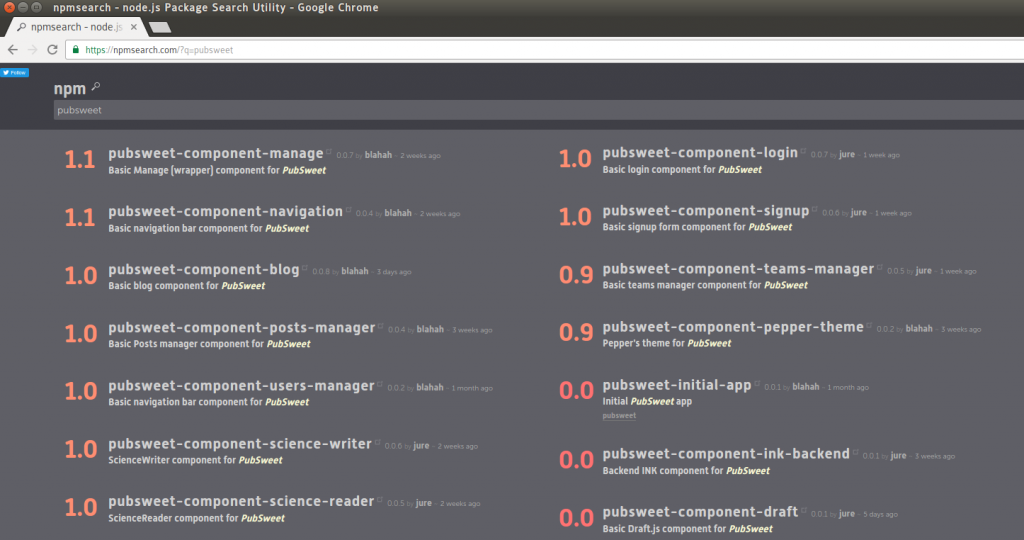

PubSweet 2

The following systems are a result of a team of very talented people at Coko. This has been the first group of people that I have worked with that enable the systems to get close to what I believe is an ideal state for the problems at hand, the time we live in, and with the technology available. If I have learned one thing over the past years, it is that, generally speaking, development teams often prevent good solutions from happening. The Coko team is a rare case where the solutions can flourish and become what they need to be. I’m very lucky to be working with such people.

PubSweet 2 is not actually a publishing platform, it is a de-coupled JavaScript framework that enables the production of multiple publishing platforms.

With all the other platforms I have been involved with I have always learned something. So the next platform is always better. Strangely enough, because when I look back I remember, for example, thinking that Booki was the best platform ever, and perhaps the best I could do. But not so. Each subsequent platform has been much better. So… why not build a framework that enables the rapid development of many platforms at once? good idea! Imagine what you could learn… Indeed!

Using PubSweet, we have developed two platforms to date. Science Blogger and Editoria. For the purposes of this blog post I’ll just focus on Editoria as Science Blogger is more of a reference implementation. However, all these front components can be developed independently of each other, and independent of the core framework. Hence we have released some PubSweet NPM modules (sort of like front end plugins) online:

If you would like to read more about PubSweet check here:

http://slides.com/eset/ismte

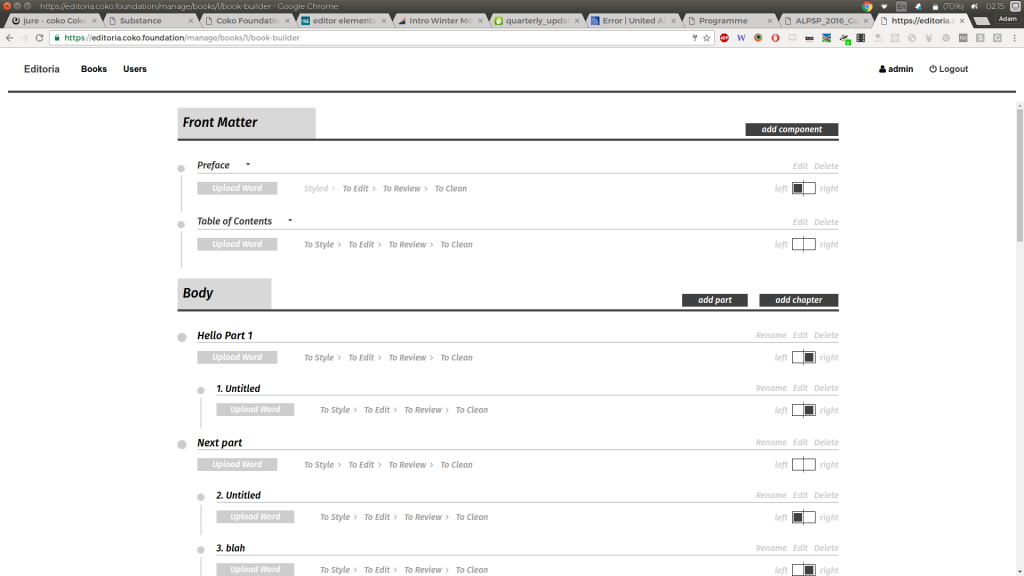

Editoria

Editoria Book Builder component

What is interesting about Editoria is that I didn’t design it. I facilitated the staff at the University of California Press to design it. And what is really interesting is that it is a better book production software than any of the above that I did design…. That’s not to say that I finally realised I was a crappy designer 😉 , rather I came to realise that given the right guidance and parameters, the people with the problems can solve the problem with more deep understanding and nuance than I could as an outsider to their processes. It was a great thing to realise.

In general, Editoria follows the same model as PubSweet 1. It is a simple collection of 3 interfaces – dashboard, book builder (in PubSweet 1 we refer to it as a table of contents manager) and a chapter editor. Very similar to PubSweet 1 and also these components fit into the conceptual schema I mentioned above of:

- produce – this happens outside the system and we convert authored MS Word files to HTML

- improve – styling, editing, reviewing, all occurs in the editor component

- manage – basic workflow managed by the Book Builder component

- share – when done we export to book formatted PDF, and EPUB

Editoria is a very simple and elegant solution. It’s the only one of the systems I have worked with that is not in production but I’m looking forward to seeing it up and running soon.

It uses the Substance.io libraries to build a custom made and elegant editor. Finally with some real $ to spend on moving this field forward, and as part of my 2015 Shuttleworth Fellowship I committed $60,000 USD (10k a month) or so to Substance, Coko followed it by a similar amount, so they could focus on the development of their libraries to 1.0. Coko also put considerable effort into founding a consortium around Substance (although I’m not convinced it is really working well yet).

http://substance.io/consortium/

Editoria brings some nice implementations to the table including the use of Vivliostyle to render PDF from HTML. Plus MSWord-to-HTML conversion, front and back matter divisions plus body content. Pagination information (left/right breaking) etc. In addition, we are building into Editoria various tools in the editor including its own annotation system and a host of publisher-specific markup options for different styles (quotes, headings etc). Coko has employed Fred Chasen for some part time work to contribute to the Vivliostyle development (although we are still working out what we should work on).

In many ways, Editoria is the system I always wanted to be involved in. It is better than any other system I have seen or been involved in and this is a result of two critical factors:

- the technologies have matured, including Vivliostyle and Substance.io, that enable critical solutions to be solved

- the people who need the system have designed it

There is more to come from Editoria, so stayed tuned…

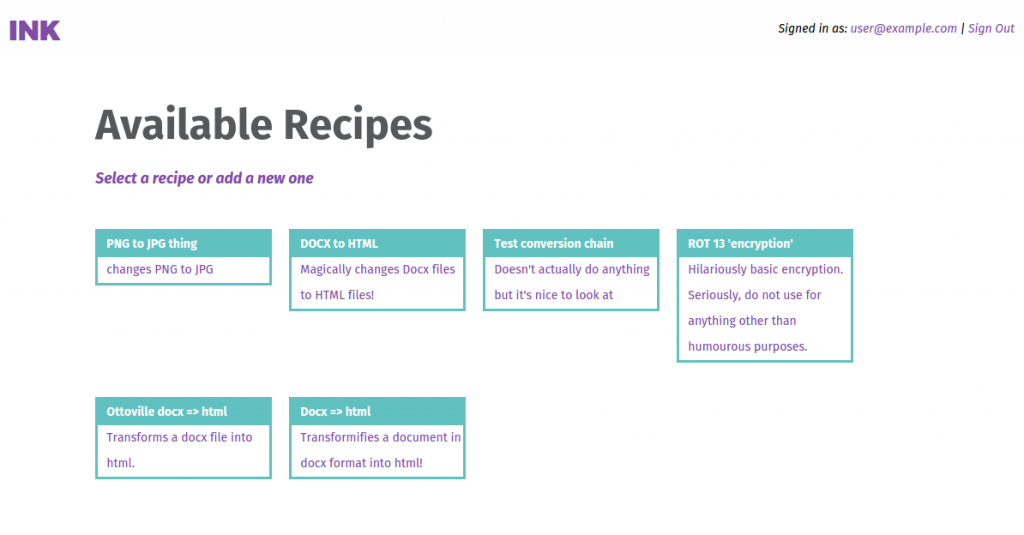

INK

INK is like Objavi on steroids. It is possibly an Objavi 4 😉 but done the right way. INK is a Rails-based web service which is primarily built to manage file conversions. However, it can actually be used for the management of any job you wish to throw at it. These jobs are what we call steps, and steps can be compiled into recipes. For example, you might have a step ‘convert MS word to HTML’ and then a second step ‘Validate HTML’. Hence INK enables you to chain together these steps.

Additionally, these steps are plugins written as Gems. A gem is a Ruby-based plugin architecture. Accordingly, you can develop gem steps and distribute them online for others to use. We hope in time there will be a free (as in beer) market around these steps.

Summary thoughts

I think I learned a lot from writing this personal ‘sense making’ piece. I didn’t realise just how strong some of the themes were that I pursued until a wrote them down…for example, I pursued collaborations from inter-organisational consortiums a number of times and none of them have worked. Huh. Interesting. I’ve also seen various practices evolve from an idea to being mature thoughts, prototypes, workable solutions and eventually, eventually, adopted. But over many more years than I expected. Also interesting.

It is also obvious that there are some big ticket technological problems that still need to be solved for good to really move forward. They are mostly there but still in need of work, the top two being:

- browser as typesetting engine

- sophisticated editor libraries

I add a third which I haven’t noted much in the above. I have worked on this since Aperta onwards and it is necessary only in the publishing world where content is authored in the legacy ‘elsewhere’ (ie MSWORD):

- reusable, sensible, MSWord to HTML conversion

This has been solved many times but has not yet been solved well.